For many B.C. families with kids in kindergarten to Grade 9, report cards will look different this year.

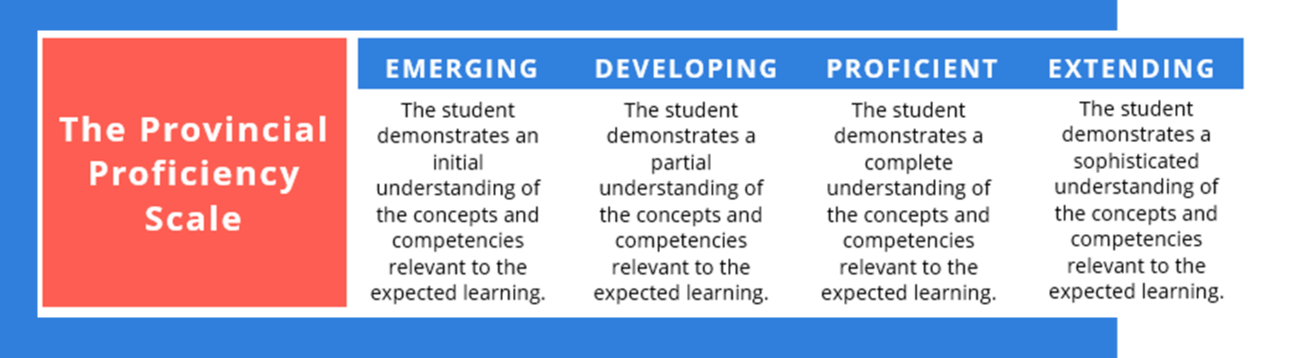

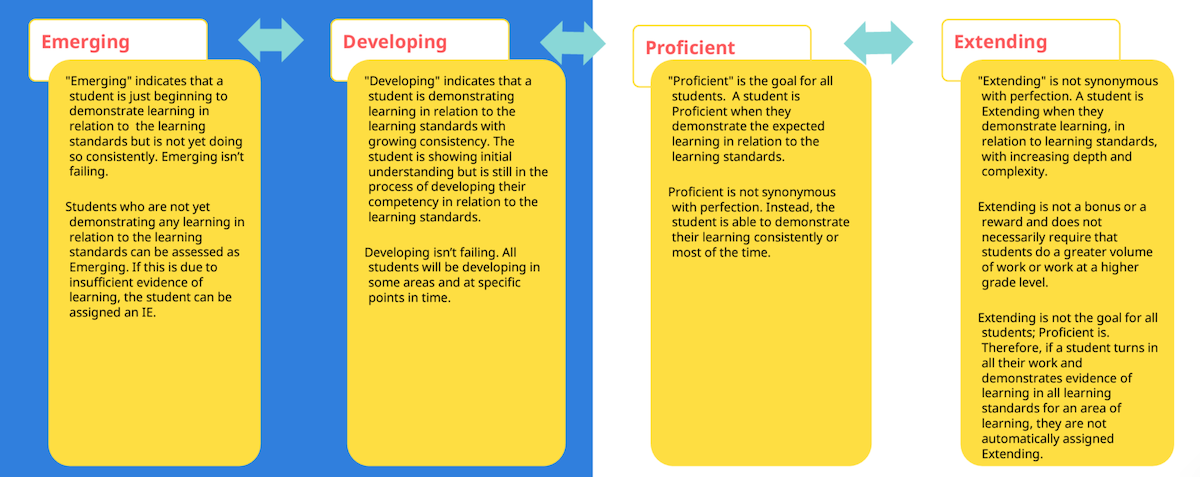

Instead of using letter grades or percentages, report cards will use a new four-point Provincial Proficiency Scale to convey what students know and where they still struggle.

The four points — Emerging, Developing, Proficient and Extending — are meant to convey where a student’s learning is from initial learning to beginning to grasp a concept, to understanding it (which is where B.C. wants all students to be), to a deeper understanding beyond what’s expected of them.

Each of the three written report cards sent home annually will include personalized comments on students’ progress for each course, as well as students’ own self-reflections and learning goals. Parents will also still receive two informal reports — via meetings, email and/or phone calls — from teachers per year.

This will not impact how students are evaluated between report cards, an Education Ministry spokesperson told The Tyee via email. Teachers will still have the freedom to use letter grades and percentage marks on students’ tests, assignments and submitted homework.

“Updating how reporting learning for kindergarten to Grade 9 students is delivered does not mean changing how students are evaluated,” the ministry’s statement reads.

“The new reporting policy has been extensively piloted, engaged on and strengthened since 2016, and at least half of B.C. students and their families are already familiar with this type of reporting as it is in place in their schools.”

Report cards for Grades 10 to 12 will continue to use letter grades and percentages, as well as a graduation progress update in their June report card.

The intention behind the new reporting method is to provide parents and students with a clearer understanding of where their child is in their learning: what their strengths are, where they need to put in more work and what their personal reflections and learning goals are.

“The B.C. curriculum and assessment model pulls together the best from modern learning theories and the expertise of B.C. teachers. We know now that students learn best when they reflect on their learning, when they actively set goals with their teachers, parents and caregivers, and when they actively participate in their learning through projects, presentations and collaborative group work,” the ministry statement reads.

The change is part of the long rollout of the province’s revised kindergarten to Grade 12 curriculum, which has been used in all B.C. schools since 2019, with some districts piloting it as early as 2015.

“It’s hard to critique this move because, in a sense, it’s really pro student, pro learning. It’s really aligned with what we know about teaching, learning and assessment. So a lot of people are for it,” said Lindsay Gibson, assistant professor of social studies and history education at the University of British Columbia, who helped draft the province’s current social studies curriculum.

But not everyone supports the move away from letter grades. Earlier this summer the Canadian Press reported a 2021 Education Ministry public consultation document revealed the majority of parents, teachers and students consulted were against the change.

“There’s an old saying: ‘If it’s not broken, don’t fix it,’” said Calvin White, a counsellor at Eagle River Secondary in Sicamous, B.C., and a former secondary English and social studies teacher.

While White admits the change is ultimately not a “big deal,” he thinks it’s “silly” to stop using letter grades and percentages in report cards.

White, who shared his stance in a Vancouver Sun opinion piece in July, agrees with the ministry and other proponents of the new reporting system when he says the most useful information teachers provide in report cards is their personalized comments.

But because we are so familiar with the letter grading scale, White says, letter grades are a great shorthand for what students can expect the teachers’ comments to reflect.

“Changing that to ‘extending’ and ‘proficiency,’ it just doesn’t give the same resonance,” he said. “That’s why there’s been questions.”

Are letter grades the ticket to academic success?

Educators have been debating the merits of letter grades and percentages for over a century.

“There’s always room for change in education,” said Michael Zwaagstra, a public school teacher in Manitoba and a senior fellow at the Fraser Institute, a conservative think tank known for controversially ranking independent and public schools based on standardized test scores. “But I want to be clear: there’s nothing new about this push.”

The BC Teachers' Federation has come out against the Foundation Skills Assessment, standardized tests for Grade 4 and 7 students in B.C., because the results are used in calculating the Fraser Institute’s school rankings. The teachers union argues test scores are not an accurate depiction of teaching quality in a school.

Zwaagstra weighed in on B.C.’s new reporting system in a column for the Winnipeg Sun earlier this summer.

“Percentage grades make it possible to differentiate between good work and excellent work more precisely than vague descriptors such as ‘emerging’ and ‘developing,’” he wrote.

Firas Moosvi, a lecturer in the department of computer science at UBC is currently working with his colleagues on an assessment of alternative grading methods in post-secondary.

Moosvi asserts the Provincial Proficiency Scale is no more vague or confusing than letter grades or percentages.

Research has shown letter and percentage grades are extrinsic or outside motivators for students, meaning they pursue higher grades for the sake of grades, not the sake of learning, Moosvi said.

“As soon as the course is over or the test is done or the week is done, it’s now all out the window: they’ve gotten their reward, they’re now moving onto the next thing,” he said, adding students who are focused on grades are less creative, take less risks in their learning and have less interest in the subject matter than those who don’t.

Parents often reward their children for high letter or percentage grades, too, Moosvi added, which tacks on another outside motivator for students to pursue.

“You’re building this house of cards where you think you’re helping students learn and grow and advance in the world, but all you’re doing is teaching them the value of being laser-focused on achieving these grades,” he said.

Zwaagstra acknowledges some students are focused on grades. But changing that is a matter of talking to students, not changing the reporting scale, he says.

“It’s not just about the mark. But that doesn’t mean the mark is unimportant,” he said, adding that if a student learns to pursue high marks in earlier grades, and eventually ends up with a scholarship as a result of that approach, it’s a good outcome.

Laura Weller, a parent and chair of the Prince George District Parent Advisory Council — one of the pilot districts that made an early transition to the new report cards — acknowledged it takes more time to read these report cards because the scale may initially be unfamiliar to parents. She added that some parents have been thrown off by the fact that students are supposed to strive to be “proficient,” but “proficient” is not the top of the scale.

“It’s easy for people to get excited about, but I don’t think it’s going to have a very material difference,” Weller said.

Does the new model represent an ‘erosion of standards’?

Removing marks on report cards “is a symptom of a bigger problem, which is this erosion of standards and clear guidelines of where we want students to be at,” Zwaagstra told The Tyee, referencing his broader view of the province’s updated curriculum.

Ken O’Connor, an Ontario-based education consultant, pushes back on this view. He says the new reporting standards are in fact stricter, because they focus solely on students’ academic performance.

Traditional grading has “included everything but the kitchen sink,” O’Connor says. “It’s been student learning, student behaviours.” O’Connor adds he’s even heard of report marks including whether a student has the appropriate school supplies or donated to the school’s food drive.

O’Connor is not totally against letter grades, calling them a “necessary evil,” in particular for Grade 11 and 12 report cards, when students may need high marks in certain courses to access post-secondary education.

White, on the other hand, is concerned that the removal of letter grades in Grade 9 will impact students’ access to post-secondary education.

“In the sciences and math you can go into the more academic stream or the less academic stream,” he said, adding letter grades and percentage marks make it easier for students to tell if they’re on track to get into the courses they need.

In an emailed statement to The Tyee, an Education Ministry spokesperson denied this would be an issue.

“While some school districts or individual schools may set course pre-requisites, receiving an ‘emerging’ or ‘developing’ on the proficiency scale at the end of Grade 9 is not intended to impact what Grade 10 courses a student can enrol in for the fall,” the statement read.

Does the new model emphasize learning over achievement?

Wendy Johnston, professional programs co-ordinator in the education faculty at Simon Fraser University, is pleased with the new reporting changes and their implication for student learning beyond Grade 9.

“All universities, including SFU, will benefit from working with students who have developed the core competency skills of learning through strength-based descriptive feedback,” she said in an emailed statement sent to The Tyee.

“Students will have had the opportunity to develop flexibility and resiliency when faced with learning challenges.”

Moosvi says students who have trained to self-assess their own learning and set educational goals for themselves from kindergarten to Grade 9 will have a leg up in post-secondary.

“Students are not trained to self-assess. When they get into university, sometimes I have students coming up to me and, even though the answer is in the back of the book, they still ask me if their answer is correct,” he said.

Weller is also in favour of self-reflection and goal setting for students because it is a skill they will need in the workforce, too.

“My kids are hard on themselves, so they clearly know where they could do better, generally. But I think it’s important to have that reflection embedded in how you go about your work,” she said.

White likes the idea in theory, but notes how effective self-reflection and goal setting will be depends on the student.

“The concept is based on the idea that kids in the classroom are fully engaged with the learning and are not just doing assignments because the assignment has been given to them. It means something to them,” he said.

“If they’re just in the class, they’re doing the assignments, they’re studying because they don’t want to fail or they want to get this mark, but it doesn’t really mean anything to them, then they’re going to give a self-assessment that’s superficial.”

How are teachers feeling about the change?

Despite the 2021 public consultation results showing poor teacher support for the new Provincial Proficiency Scale, BC Teachers’ Federation president Clint Johnston says the majority of the union’s 50,000 members are now in favour of the new report card model.

The 2021 survey was done when the changes were “still really speculative,” and teachers didn’t have enough information to come to solid conclusions, Johnston says.

Since that time the province has put information online explaining the changes for students, parents and educators, an eight-part webinar for educators and administrators, as well as a 30-minute video presentation for parents on their website.

While Johnston supports the reporting change, he does want to see the province invest in teacher in-service training.

“I don’t think this reporting order in and of itself is going to increase any workload for any people. As usual it’s going to be how it’s implemented on the ground,” he said.

“That type of training is essential when you roll out any kind of large-scale program that’s going to change the way people do things.”

Like many people who spoke to The Tyee for this article, Gibson anticipates a backlash from some segment of the public over the change — especially if the ministry and districts fail to fully and properly inform teachers and parents about how the Provincial Proficiency Scale works.

Gibson also added in order to assess whether the new reporting method is beneficial or not, the province will need to commit to it long-term.

“I hope they give it a good try,” he said. ‘Not just six months, but let’s see what it would look like for five years, for 10 years.” ![]()

Read more: Education

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: