“One, three! No — five Dungeness crab! And there’s the dogfish!” cries Joe Valencic, peering into his hand-held viewing device.

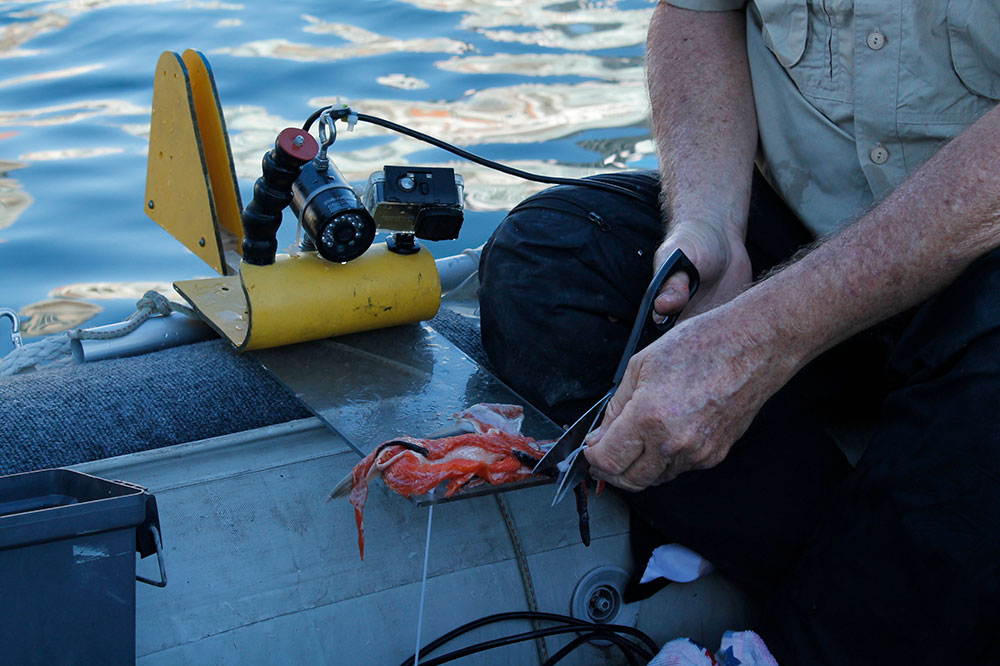

He’s perched on the side of a grey dinghy tethered beneath the Burrard Street Bridge, watching a live feed coming from a camera resting on the bottom of False Creek, six metres below the surface of the murky waters of the Pacific Ocean.

Valencic, a marine biologist, spots one spiny dogfish shark, then two, then three on the feed — then loses count.

A minute later diver and underwater photographer Fernando Lessa surfaces, spitting out his regulator.

“There’s 10 sharks down there!” he says.

The crew standing on the boats tethered beneath the bridge break into excited cheers.

Meet False Creek Friends, a collective of aquatic enthusiasts working towards improving the inlet.

Today they’re working with Lessa to photograph the wild landscape under the surface of the murky waters.

“When you look at the ocean floor it moves because there’s so many crabs,” Lessa says. After spending half an hour diving, photographing and resurfacing to chat with members of False Creek Friends, Lessa passes his heavy underwater camera to waiting hands on the boat and hauls himself out of the water.

He glances back down, somewhat uneasily. “The sharks were all around me — they even tried to bite my lights,” he says.

Spiny dogfish are usually smaller than a metre in length and eat small fish like herring or crabs. Valencic laughs when asked if they’re a danger to humans, and shakes his head.

The organization’s long-term goal is to better False Creek so that one hot, future summer day any Vancouverite can walk down to the beach near Science World or Granville Island and jump into the refreshing, healthy ocean, says board member Tim Bray.

But there’s a long way to go before that goal can be realized.

Until the 1950s False Creek was the industrial heartland of Vancouver, according to a city spokesperson. Sawmills, ship building, coal gasification plants, small port operations and other industries supported the railway terminal, with waste pumped directly into the water “for many years.”

In the 1960s the area was further industrialized, which deteriorated both the aquatic habitat and water quality significantly, they add.

It’s still advisable to keep your head out of the water today.

Vancouver Coastal Health strongly recommends against submerging yourself in False Creek because of high levels of E. coli in the water. A City of Vancouver spokesperson told The Tyee that kayaking, paddle boarding and other activities that keep most of your body out of the water are OK.

High levels of the bacteria can “increase the chances of gastrointestinal illnesses and skin/eye infections,” according to the health authority.

Beaches around the city can be closed if there is more than 400 E. coli found in 100 millilitres of water. On Aug. 12, Vancouver Coastal Health said the waters around Science World contained 4,360 bacterium — definitely unsafe for swimming. On Aug. 18 that number had dropped to 520.

But that could change, says Zaida Schneider, co-founder and president of False Creek Friends.

Schneider points to Plymouth, a city in the United Kingdom, which is working on cleaning up Plymouth Sound and turning it into a national marine park. If it can happen in a heavily industrialized waterfront in the U.K., it can happen in Vancouver, he says.

The goal is to improve the waterway, Schneider says. This may or may not mean turning False Creek into a federal Marine Protected Area.

But before you clean something up you need to know what’s making the mess in the first place.

To help answer this question False Creek Friends is partnering with the Hakai Institute, a B.C.-based research institute that focuses on marine ecosystems, which will run a “BioBlitz” at the start of September. (The Tyee receives funding from Eric Peterson and Christina Munck, who also fund the Hakai Institute through the B.C.-based Tula Foundation. Neither the Hakai Institute nor the Tula Foundation had editorial input on this article.)

The BioBlitz will bring together around 33 scientists and academics for five days of research from Sept. 3 to 7 in and around the inlet, says Matt Whalen, a postdoctoral scholar with Hakai who is organizing the event.

“We’re working on building up a species inventory of all life in the area,” Whalen says. “We’re trying to cast a pretty broad net on biodiversity from coastal habitat to riparian and the seafloor.”

“We need to know what’s happening in the natural environment if we’re going to understand how things change with climate change and continued development,” he adds.

The event will bring out experts on seabirds, insects and animal identification (from plankton to the worms that live in the sediment). Whalen adds that they’re hoping to add specialists in plants and small vertebrates.

This research will help show us how False Creek is recovering from its industrial history and could help inform future development or rehabilitation plans, he says.

The four core projects of the BioBlitz will be to create a species inventory, to study what organisms grow on surfaces, to study the life on and in the seafloor and to test the waters to see what species’ DNA can be found, Whalen says.

To create a species inventory Hakai researchers will be partnering up with citizen scientists, who will help record what species they find through the iNaturalist app.

Researchers have hung tiles, or settlement plates, on various underwater places around False Creek to test the biodiversity of the “fouling community,” which refers to creatures like mussels and barnacles, which grow on solid underwater surfaces like docks, pilings and boats.

During the BioBlitz researchers will pull the settlement plates out of the water and categorize the life growing on them, which will help show the gradient of what species can and can’t flourish the deeper you get into the inlet, Whalen says.

Researchers will also be studying the animals that live on the sea floor and in the sediment on the bottom of the inlet.

“The reason why those communities are so important is they tell us a lot about what the environment is like,” Whalen says. “So if we sample communities in False Creek and see from one end to the other the communities change, we can pretty well associate that with things like water quality and overall state of the ecosystem.”

The fourth main project will combine oceanographic samples that measure the temperature, saltiness and depth of a given area. This information will be integrated into mapping the biodiversity gradient of False Creek, Whalen says.

Researchers will then do an Environmental DNA test on the water sample to check what organisms or fragments of DNA show up in the sample, he says.

“We can use molecular techniques to say something about the biodiversity of organisms that are in the area,” he says.

The data collected during the BioBlitz will become publicly available, Whalen says. Most of the data, like species inventories, will be available in the weeks after the event but some, like the molecular analysis, will take months, he says.

All of the research will be published within the year, likely by early 2023, he adds.

“This data will help us understand how the system is changing and give us a benchmark for how it could change in the future,” he says.

The City of Vancouver and False Creek Friends will be using the data to brainstorm ways to improve the inlet.

The city is part of the planning committee for the BioBlitz, is providing research space and will use the generated data to “inform ongoing city and park board work on coastal adaptation, the city’s Healthy Waters Plan and general environmental planning,” a spokesperson said.

The city is aware that herring spawn in the inlet, and that the waters are home to cormorants, harbour seals, overwintering migratory birds, Dungeness crab and dogfish, they added.

wild #Falsecreek

— Fernando Lessa (@fgclessa) August 9, 2022

Today I partnered with @false_creek to explore the wild side of False Creek.

It was a pretty intense experience being surrounded by 10 dogfish in 30cm vis. water. pic.twitter.com/QixSqICOKe

Cleaning up the False Creek will also mean cleaning up derelict, abandoned and sunken vessels, says False Creek Friends board member Bray. But that’s not as easy as calling in some marine tow trucks.

It’s free to anchor your boat for up to two weeks in False Creek from April 1 to Sept. 30, and for three weeks from Oct. 1 to March 31, but you need an anchoring permit.

Often, Bray says, people are living on boats in False Creek because “their back’s up against the wall and they’ve got nowhere else to go.” Other times, people will moor their boat and leave it for more than six months at a time.

That means ships can be in poor repair. If an authority tows a boat they take responsibility for it — meaning if it sinks it’s their fault, Bray says. Dismantling and disposing of an old vessel can be expensive, hazardous work, he adds.

Punishing someone who is unable to maintain their boat for financial or health reasons is also unfair, Bray says.

Lessa says he’s seen large batteries and bikes on the bottom of the inlet. Schneider says he’s heard stories about a canoe and a full fishing boat, with the fishing rods still hanging off the boat, resting on the bottom of False Creek.

As Schneider drives his boat back to the Heather Civic Marina, he points to the high cement walls and thick metal fences that separate the seawall from the water. This protects the city from high waters but also cuts people off from the ocean and tells them to ignore the water, he says.

As sea levels rise due to climate change, over 38,000 residents and 200 industrial properties will be vulnerable to flooding around False Creek, according to the city. There’s a lot of different ways the city could adapt. The city could raise the seawall (which could cost up to $850 million) or unbuild the seawall and rebuild a marshy foreshore.

Back at the marina, Lessa grabs his camera and jumps back in the water. He’s trying to photograph silvery schooling anchovies.

Standing on the dock, Schneider asks Lessa if he’s ever concerned about exposing himself to E. coli while photographing underwater in False Creek.

Lessa spits out some water and laughs. “I’m from Brazil!” he cries. People swim in more polluted water on tropical vacations all the time, he adds.

He dunks back underwater before popping back up.

“Zaida! I saw a salmonoid! I think it was a Chinook!” he cries. The photo is blurry but Lessa says the size and colouring of the fish confirms it.

False Creek is far from dead. There’s a lot of work ahead, but its recovery is only getting started, Schneider says. ![]()

Read more: Science + Tech, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: