In the 1870s, Israel Powell, the superintendent of Indian Affairs for B.C., made several trips up the northwest coast. Though he was ostensibly visiting First Nations as part of his job, Powell also used these trips to collect hundreds of Indigenous cultural belongings for himself as well as for museums in Canada and the U.S.

It was most likely on one of these trips, according to Douglas Cole’s 2014 book Captured Heritage: The Scramble for Northwest Coast Artifacts, that the commander of the naval ship HMS Rocket decided to rename a northwest coast river and its surrounding area after Powell.

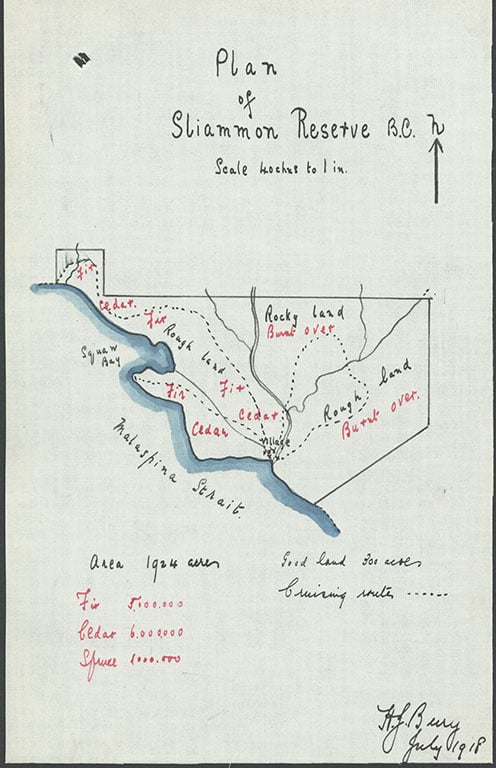

According to John Hackett, Hegus (“Chief,” in the Sliammon language) of the Tla’amin Nation, the Tla’amin people had, at that time, a main village called Tis’kwat located in that exact spot. But the people started seeing European settlers coming into their territory, setting up camps and eventually starting to log and extract resources from the area.

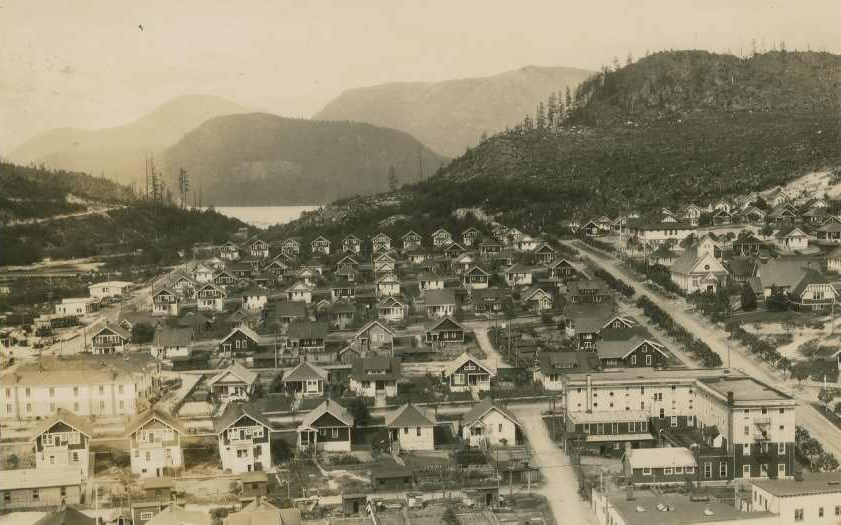

Eventually, the area was populated by a mill, settlers and their houses — and the government moved the Tla’amin Nation away from its main village onto a reserve north of the townsite. Today, Powell River is a city of more than 13,000 people, including newcomers making the “pandemic pivot” from big city living to a quieter, cheaper lifestyle amidst natural beauty.

But the Tla’amin are looking for a different pivot. They say reconciliation must include demonstrated respect for their heritage and the return and protection of their cultural artifacts. Ideally, they say, it would include renaming the town itself. The new name would celebrate the people whose ancestors have been here for thousands of years, rather than the man who came to steal and colonize, Israel Powell.

If that sounds like a bold proposition, it’s also one being taken seriously by some in Powell River, including by its mayor and council which voted unanimously to explore the option.

The City of Powell River and the Tla’amin Nation are engaged in a reconciliation process that began with a community accord in 2003. But it’s been rocky from the start: in redeveloping the waterfront around the ferry terminal in 2001, the city bulldozed important Tla’amin cultural artifacts, including petroglyphs. The city’s initial agreement to address the harm included ensuring the nation could protect the land and granting the nation the contract to finish the seawalk.

The development of the initial agreement eventually led to the community accord. So far, the reconciliation process has included putting the Tla’amin flag up next to Powell River and B.C. flags at city hall, as well as ensuring both communities, along with the qathet Regional District, meet many times a year.

Powell River and the Tla’amin Nation also signed a Protocol Agreement on Culture, Heritage and Economic Development in 2004, which sets out to protect and promote the traditional culture and heritage of the area and have the parties work together on economic ventures.

And just two years ago, the accords and agreements led to the renaming of the Powell River Regional District to qathet Regional District — a name that was gifted by the Tla’amin Nation and that means “working together,” said Hegus Hackett.

Now, the Tla’amin Nation is hopeful for further action: a name change for the city itself.

“I just got elected last year as Hegus, and I started to do a little bit more research on how Powell River became Powell River, and the more research I did, my heart sank into my stomach,” said Hegus Hackett.

“A lot of their business interests took priority over our interests, and it led to us being removed from our original village site,” said Hackett. “Our town is named after him. It’s just… it’s a punch in the stomach.”

A report titled “Israel Wood Powell’s Legacy,” commissioned for the nation and compiled by an organization called Know History, draws from the Library and Archives Canada, historians and Indigenous organizations to outline how Powell, as superintendent, directly attacked coastal First Nations’ rights and sovereignty, including those of the Tla’amin people.

Powell’s career with the Department of Indian Affairs, the report concludes, “was characterized by his advocacy of assimilationist policies designed to ‘civilize’ the First Nations of British Columbia.”

Powell pushed for the creation of Indian residential schools, including the Kamloops location, where 215 Indigenous children’s bodies were uncovered this summer.

He also took over 1,000 sacred and ceremonial items, skulls, stone tools and other objects from the Indigenous people he worked around.

And he helped create the government’s ban on potlatch ceremonies, which became part of the Indian Act in 1884 and didn’t end until 1951. This ban could result in a six-month jail sentence for anyone caught participating in the tradition.

“‘Patlatches’ [sic], no doubt, not only retard civilizing influences, but encourage idleness among the less worthy members of a tribe, and will, I trust, by wise administration become obsolete in time,” Powell wrote in his Report of the Superintendent of Indian affairs, for British Columbia, for 1872 & 1873.

Powell’s references to “civilizing” Indigenous people are found in his own writings for the government. For him, to “civilize” really meant “to remove Indigenous culture, religious practices, education and government structures, and replace them with Euro-Christian ones.”

The report also confirms what Hackett said — Israel Wood Powell was instrumental in the forced removal of Tla’amin people from their village, which became Powell River.

The land, known as Lot 450 to the government, was a 15,000-acre site that also included village sites from the neighbouring Homalco and Klahoose people. Powell intentionally dissuaded an Indian land commissioner from meeting with the local Indigenous nations, to prevent him from acting on the concerns they had expressed around losing this territory.

The site was then sold to a Victoria politician who used it for timber logging.

A call to return sacred artifacts

Israel Powell, though one of the worst offenders, isn’t the only one who took sacred items from Tla’amin territory and desecrated sacred sites.

The issue has led to the Tla’amin Nation putting a call out for any appropriated items to be sent back to them, no questions asked. The theft of items from their territory has been a problem over the years, according to Drew Blaney, manager of the cultural activities and information department at the Tla’amin Nation.

“We know that in early years, people were collecting the skulls of our ancestors out in our territory, because we used to bury our loved ones out on one of our islands. And now the area is a very popular provincial marine park, so quite a few boaters came through,” said Blaney.

“In the early years, there was kind of like a competition to see who can collect the most skulls and have that displayed on their boats,” he added, noting that the time period he’s referencing stretches from the early 1900s to around 1960.

Though many ancestors were disturbed and taken from their burial sites, only some have been returned, he said.

Since putting the call out in March, a number of woven baskets have been sent back from as far as Seattle, Toronto and Calgary. Not all of these were stolen, said Blaney. Some had been sold by community members during the Depression era for income.

A number of historical shaman rocks, net weights and arrowheads have also been sent back. These items have often been found when people were digging up their gardens, or on beach walks, he said.

The community is asking for the repatriation of such items to continue, emphasizing that they’re not holding anyone accountable in the process, but asking for items to be returned anonymously.

This March, the Tla’amin Nation also asked for help from the B.C. government, under the Heritage Conservation Act, following the desecration of a burial site by a local developer. The nation is requesting an archaeological assessment carried out by an independent third party — not one carried out by someone chosen by the developer, as was done already, said Hackett.

The Tla’amin Nation have been in talks with the government about the issue. Meanwhile, the developer says it has specifically respected sensitive areas outlined by the provincial government, and the building continues.

“That’s one of our village sites, too,” says Hackett. “There’s Oral History there. There’s a lot of burials out there, including past leaders that were out there. There’s Oral History of a smallpox outbreak that happened on that site, and there’s a lot of burials along the creek,” said Hackett.

The Tyee reached out to the provincial government for comment. While the government confirmed it was still in discussion with the Tla’amin community, it said nothing about any concrete action at this time.

A ‘black eye’ on the community

In May, Hegus Hackett and his council approached the city to request a name change. Since then, they’ve met with the Powell River mayor and city council and also written a letter to them about the request.

It was after learning of that request that members of Know History say they offered to work together with the Tla’amin Nation on the complete history of Powell.

In October, the city approved a budget for a joint working group, including two city council members, two Tla’amin Nation members and two citizens of the city to explore the name change. The city asked that Tla’amin contribute funding for the working group as well.

But Hackett is not willing to put Tla’amin Elders or youth through a working group process until the change is more certain.

“We don’t want to engage with our Elders and get them all riled up and say we might change the name of Powell River, and at the end of the day they don’t change it. It would be another stab at them,” he said.

The nation has felt some pushback, Hackett added. When the Powell River Peak has posted news stories about the name change, online commenters have attacked the idea. Powell River council members have told him they do see the name as a “black eye” on the community but worry if they publicly voice support for a change they’ll be voted out, he said. “It’s just frustrating, seeing politics is taking over reconciliation.”

The city council has suggested holding a referendum on the issue to Hackett, but he believes that because the Tla’amin people are such a minority in the area, the motion wouldn’t pass.

Many Tla’amin Elders attended residential schools and suffered considerably at the hands of government officials. Elder Elsie Paul, who was featured in a Tyee story last year, was just a little girl when RCMP officers forced her to tie her dog, Patsy, to a post, then shot the dog in front of her.

“I see reconciliation as a second attempt at a broken relationship, and it takes both parties to reconcile what went wrong,” said Hackett. “My honest gut feeling is that they’re pushing a lot of the heavy lifting and the work onto the nation.”

Powell River Mayor Dave Formosa points out that council’s motion to begin talking with community members about the potential change passed unanimously. After they strike their committee, he said, they will engage in public education seminars.

Some of those seminars will be “coffee and doughnut chit chats” between Tla’amin members and Powell River residents, and city council may even have a play created by the local theatre group that speaks to the cause, said Formosa.

But there is no set timeline, and he can’t guarantee the change will ever happen.

“It’s not a definite,” he said. “We are going to work with our folks so that they can understand and learn why they want a change.”

“I mean, I was born here. I never knew stuff about Israel Powell. I didn’t know who he was. I just thought Powell River was the name of the river. And at the end of that river was the dam that made power for the mill. And I was born in Powell River,” he said.

He and other settler residents need to learn more, Formosa said. “What we’re hoping is that we will educate and communicate with” residents of Powell River about the man who bestowed his name on their town, in order to help “the folks realize that this is hurtful.”

“Right now, they don’t understand. They have no clue.” ![]()

Read more: Indigenous, Rights + Justice, Municipal Politics

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: