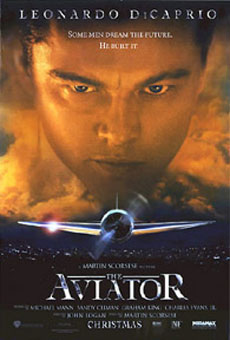

The opening scene of Martin Scorsese’s award winning biopic The Aviator shows us young Howard Hughes being sensuously towel dried by his mother who murmurs to him about the unsafe world around them. A cholera epidemic is rampant and she carefully teaches him to spell the word “quarantine.” The images are slow, shadowy and ominous. They provide the dark undercurrent which frames this otherwise fast-paced, opulent, and stylish romp through the glamorous life of Howard Hughes.

We watch as Hughes constructs a risk taking, ambitious life producing motion pictures, building an airline company and dating Hollywood’s most appealing actresses.

At the same time we see him increasingly struggle with tantalizingly bizarre fears and obsessions that begin to undermine all aspects of his life. We are witnessing the relentless spread of the obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) that eventually transformed Hughes into a paranoid, tormented hermit.

Biopics promise us insights into the complicated lives and times of fascinating people. Certainly Scorsese’s account of Hughes’ life offers intriguing insights into the development of the aviation and motion picture industries. Hughes’ exploits in his professional and personal life are revealed in lavish detail. However, the mental illness that shaped Hughes’ life is dealt with in a shockingly dated way that leaves audiences as ignorant of the disorder as was Hughes himself. So far, reviewers who even address the roots of Hughes’ troubling illness content themselves with the widely discredited Freudian framework that Scorsese has carefully constructed. These reviewers refer to the scenes of Hughes’ mother planting the seeds of his later terror of the world to explain the disorder that is at the centre of the film.

Freud’s compelling fiction

The Freudian perspective, which posits the origins of mental illnesses in early childhood experiences, provided the arts with convenient and dramatically rich material for most of the previous century. However, by the late 20th century the psychology and psychiatry fields, ultimately linked to the evidence based practices of science, were transformed by crucial breakthroughs in brain research. Serious mental illnesses are now seen as disorders of the brain. Much has become known about the stuck loop of the faulty neurotransmitters that produce the agonizing symptoms of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Interested readers can learn more, including information about successful treatments, at many websites including that of the 10,000 member Obsessive-Compulsive Foundation.

Interestingly, Scorsese lists Jeffrey Schwartz in the credits of the film. This UCLA based psychiatrist includes descriptions of Hughes’ obsessive behaviour in his book Brainlock: Free Yourself from Obsessive-Compulsive Behaviour. Scorsese’s research enabled him to be very successful in capturing the nuances of the experience of OCD. He vividly recreates, for example, a famous incident that is also in Schwartz’ book; Hughes left his dinner companion for an hour and a half as he went into the restroom. He had felt compelled to completely wash his clothes in the sink after getting food on himself. He then had to dry his clothes and, like many OCD plagued people who fear the germs on door handles, had had to wait for another customer to open the door of the restroom before he could escape.

At other points in the film Scorsese deftly utilizes camera and editing techniques to create Hughes’ skewed perceptions. Especially poignant is Hughes unsuccessful struggle in one scene to stay focused on a discussion in a crucial meeting when he’s fixated on the crumb on his companion’s jacket. Scorsese brilliantly uses film to animate the terrors of a mind wracked with paranoid obsessions. However, he has chosen to ignore the non-Freudian, less dramatically charged brain-based explanation of obsessive-compulsive disorder that Jeffrey Schwartz carefully outlines in his book.

Where the real stories are

Scorsese isn’t alone among Hollywood filmmakers who continue to ignore the most basic information about mental disorders as they construct storylines that are familiar and comfortable. In Matchstick Men, Nicholas Cage does a superb job of presenting the frantic fears of the OCD afflicted protagonist. In keeping with the intent of the theme of the film, we see this protagonist overcome his disorder not with the medication he thinks helps him but with a placebo supplied by his sleazy friend. Even the most casual survey of research literature about OCD shows it to be a disorder that never responds to placebos.

People who live with brain disorders are all around us. Research suggests that two percent of people struggle with OCD. About one percent of the population suffers from schizophrenia and one percent have bipolar disorder. In spite of breakthroughs in scientific research that have led to increased understanding and improved treatment of these disorders, the wider community remains uninformed about mental illnesses.

Although a few films and televisions dramas do include accurate representations of life with these disorders, too many writers and directors have been slow to abandon their older storytelling habits. The unsubstantiated theories that led people to believe that families are the cause of OCD, autism, and other serious mental illnesses caused tremendous damage to patients and families. These family-blaming theories postponed the development of the desperately needed services that people with brain disorders are only beginning to get. These are the stories that promise the motherlode of unmined dramatic material that informed writers are finally beginning to tap. This much needed public understanding about the roots and processes of serious mental illnesses will finally enable its victims to escape the social “quarantine” that too many have to endure.

That Scorsese offers in this award winning film, at this point in time, the discredited view of OCD that he does, and that film reviewers fail to notice this problem, tells us how far we need to go in creating the much needed artistic insight into our collective experience with mental illnesses.

Susan Inman is a former arts journalist who has worked for many years as a secondary school teacher. She is the mother of a daughter who bravely battles mental illness. ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: