Forty-nine years ago, in June 1975, the movie Jaws opened in theatres. Things have never been the same since for sharks in the public imagination.

While the greater population freaked out about killer fish swallowing humans whole and coming back for seconds, the reality is altogether more nuanced and a lot less gruesome.

Sharks eating people is still something of a rare occurrence, despite the preponderance of Shark Week specials and B-grade movies featuring sharks in tornadoes, sharks gobbling up Paris or sharks melding with octopuses into an unholy conglomeration of teeth and tentacles.

In fact, sharks are extraordinary models of design, breathtaking in their elegance and charisma. Nothing makes this more evident than seeing the real thing, up close and personal, at the Vancouver Aquarium. The sharks on display are not the beastly megalodons or great whites of film stardom and childhood nightmares. They’re much sleeker, smaller beasts.

Blacktip reef sharks make their way around the main tank in the Tropics exhibit as sharp and fast as fighter jets.

Knife-edged, they slice through the clear water with purpose and precision. As aquarium biologist Darin Hinschberger explains, blacktips are ram ventilators, meaning they must swim constantly to keep water moving over their gills to breathe.

Other species, like tiger sharks and nurse sharks, can seemingly park themselves on the sea floor and just hang out. While not exactly sleeping in the conventional sense, this activity is a form of deep rest.

While the sharks appear to be stationary, they’re actually engaged in a process called buccal pumping, meaning they’re drawing water into their mouths and then out over their gills.

Like their larger cousins the great white and whale sharks, blacktips must move constantly to get enough oxygen. This move-or-die imperative gives them a particular relentlessness. But, as Hinschberger says, they’re so well fed that the other residents of the tank have little to fear.

The other fish are so relaxed with their neighbours that they will occasionally use the sharks as scratching posts, rubbing against the shark skin in the wrong direction, so that it acts like a Brillo pad for any fish that has an itch.

Super-sensory powers

Sharks are, in some sense, perfect. Their basic design has changed little since the time of dinosaurs. Researchers have been studying them for several reasons, such as the fact sharks rarely get cancer. But the more information that comes in, the more extraordinary they become.

The ability to read people’s heart rates and the level of electrical activity in their bodies is not so much an extrasensory power as a super-sensory one.

The wonderfully named ampullae of Lorenzini are what allow sharks to gauge the electrical impulses of other creatures in the ocean.

The small black dots that pepper the snout of a shark are pores connected to gel-filled chambers (the ampullae) that are richly lined with nerve cells. These organs are so sensitive that they can detect the electrical impulses created by muscle contractions in potential prey.

This very acuity is what allows scientists to stun sharks into a semi-coma by rubbing their snouts, thus overwhelming this sense, and then flipping them over. This activity is best employed on smaller sharks, so don’t go getting any grand ideas about tipping a great white.

Equally powerful is a shark’s sense of smell. Sharks can detect blood in the water (one part blood to one million parts water) even from considerable distance.

As Hinschberger notes, it is important to be calm when dealing with sharks. They are designed by millennia of evolution to sense any kind of panic or injury.

So, if you do find yourself in the ocean with a bunch of sharks, just be cool, man.

A peaceable kingdom

Blacktip sharks are, in fact, pack hunters. At the aquarium, the two larger males and trio of smaller females swim in constant circles. The females are almost indistinguishable from one another, except for a notch in the dorsal fin of one. The sharks are kept well-fed, in part to mitigate any predator response, and to maintain a kind of peaceable kingdom.

Their food, squid and other fish, is also not fed live, which would fire up the old sharky impulses to, you know, behave like they do in the many scary movies dedicated to their intensity.

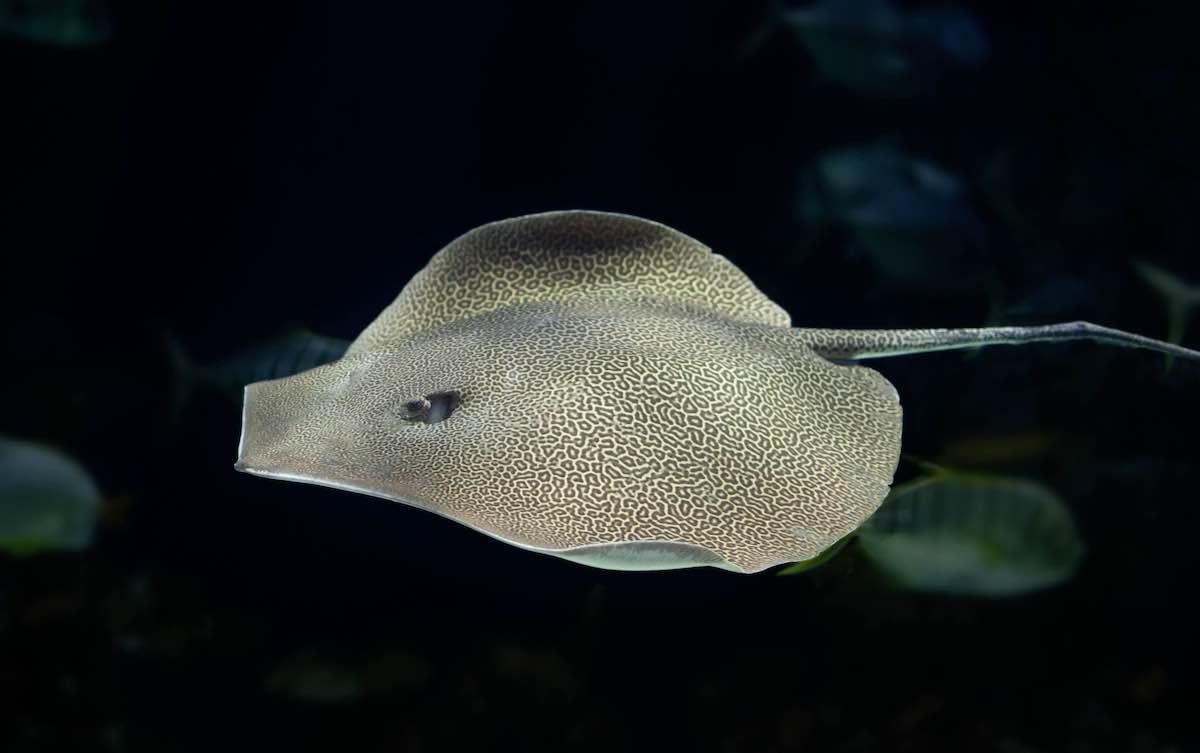

Beyond the sharks, another extraordinary presence in the Tropics exhibit is the reticulate whipray affectionately known as Big Boy. A more spectacular creature is hard to imagine. Large, drapey and dappled with a mesmerizing pattern of dots and dashes, the reticulate whipray is often called a leopard ray, as it recalls the similar pattern of a big cat’s coat.

A bottom-dweller, Big Boy eats a varied diet that includes clams, oysters and other small fish. As Hinschberger says, the ray’s eating habits are often very funny, from using its snout to flip food to its underside to the employment of its long whippy tail as a means of preying on fish.

The tail comes in handy in other ways. Communication with the other tank inhabitants is rendered explicit by Big Boy’s long lash that culminates in a poisoned spine at the end.

The ray is first in line for feeding. If any impatient sharks make to muscle in on the action, the tail comes up, a clear indicator to back off, lest there be unpleasant repercussions.

One thing that has always interested me about animals is their often very direct form of communication, as well as their etiquette.

I grew up in the Kootenays, where it was not an uncommon experience to bump into a bear while trying to catch the school bus. Most often, they (the bears) ambled off, looking sheepish. If they possessed a trilby hat, they might have doffed it with a mumbled apology. “So sorry for startling you, madam.”

The inhabitants of the tropical tank appear equally well-mannered. In the wild, blacktip reef sharks might bite the occasional human who insists on wading in the same shallow waters that the sharks call home. Most often, these bites are purely accidental and come from the sharks trying to get food.

The worst aggressors look benign

Other creatures are a little less chill.

You might think that sharks would be the most aggressive creatures on display at the Vancouver Aquarium, but you would be wrong. The real aggression is happening in the most benign-looking place. Corals are busily engaged in an epic struggle over resources, territory and food. As Hinschberger puts it, “It’s constant war.”

The notion that nature is benign, even co-operative, is quickly put to rest by the behaviour of coral. Not only are different varieties competing, but they’re also on the hunt for more territory. These turf wars employ investigative strands called sweeper tentacles that search out new places for coral to expand, but if they encounter other coral doing the same thing, well, look out.

This particular fact took me by surprise. One of the great joys of visiting the aquarium is exactly this. Even in the space of a few hours of looking at things and touring about, I learned all kinds of stuff. Some of it relatively prosaic, like the robust number of engineering staff at the aquarium.

On a quiet Wednesday morning, before the aquarium has opened to the public, the people who maintain the generators, filtration systems and other vital behind-the-scenes stuff are hard at work. So, too, are the number of veterinary workers who attend to the requirements of the aquarium’s inhabitants.

Then there is the more esoteric stuff, like enrichment programs for the different animals. While staff are cleaning the tank in the Amazon section, a caiman drifts close by, apparently undisturbed, its heavy-lidded eyes and slack-jawed demeanour reminding me of certain stoners I have known.

On the floor of the gallery, a large iguana is moseying about. As part of the enrichment, different animals are allowed out of their usual sections in the facility and availed of other things to see and do.

As Hinschberger explains, sometimes staff pick up the iguana and run pell-mell around the aquarium to let them feel the wind through their hair or maybe spines. Enrichment for the animals at the aquarium differs greatly depending on the species.

Another example of adding fun and interest involves offering a group of carpet sharks food in large mesh balls that require them to use their minds and skills to figure out how to get at the individual pieces as they would prey items from small crevices in the wild.

After a period of time spent observing animals, I feel my heart rate drop. A strange species of calm steals over me.

It’s a curious feeling of peace, so absolute that sharks, with their great capacity to sense stress or alarm, would perhaps even think, “Dang, that’s a cool and collected human.”

Just stay away from the coral, if you know what’s good for you.

The Vancouver Aquarium is hosting a special event highlighting sharks on July 14 in honour of Shark Awareness Day. In addition to talks from shark experts, attendees will have the opportunity to watch aquarium staff dive with and feed the sharks. ![]()

Read more: Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: