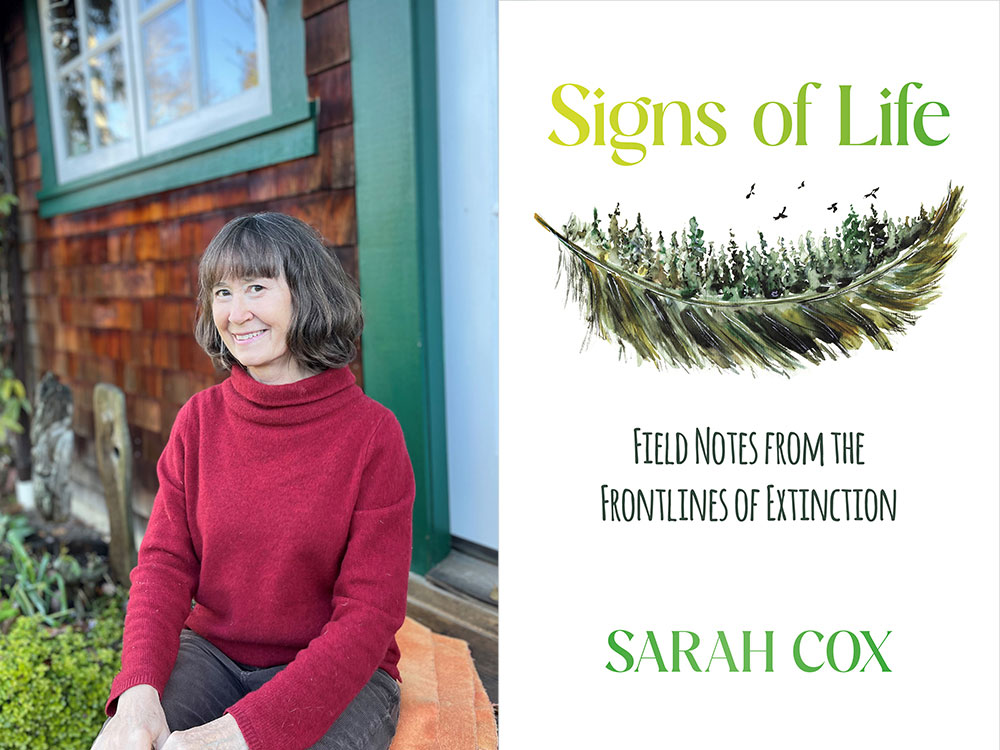

[Editor’s note: The newest book from environmental journalist Sarah Cox, ‘Signs of Life,’ delves into the world of species on the brink of extinction in Canada, following the stories of the activists, scientists and Indigenous guardians who are endeavouring to help save them. This excerpt zeroes in on B.C., which is home to the country’s last three wild spotted owls.]

It took some time, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, to organize a trip to the valley where Canada’s last breeding pair of wild spotted owls lived. But finally, on a sunny, uncommonly hot day in April 2021 that foretold of the wildfires that would later tear through parts of the Fraser Canyon, I met up with Joe Foy in Hope.

He wore a green ball cap and hiking boots and had a boyish appearance despite his greying hair. He’d grown up on a chicken farm in Langley, he told me, and worked at a poultry operation in the Fraser Valley before becoming a Dairy Queen franchise owner in downtown Vancouver’s Gastown. A chance encounter with the Wilderness Committee led him to take a short-term job working on the group’s conservation campaigns. After that, he’d headed the committee for 20 years before dabbling in semi-retirement as the group’s protected areas campaigner.

Most of the old-growth forests surrounding the Fraser Canyon had been logged, leaving behind patches Foy referred to as the “guts and feathers.” Some guts and feathers remained in Spuzzum Valley, next to the wildlife habitat area where the breeding pair of spotted owls nested. To Foy’s dismay — but not surprise — the B.C. government had recently approved new clearcuts in the valley. BC Timber Sales, a government agency, had begun to extend a logging road, advancing ever closer to the area where the owls lived. I soon became acquainted with Foy’s impressive vocabulary of expletives.

Before heading into the valley, we rendezvoused with Chief James Hobart of Spuzzum First Nation. Hobart greeted us with a broad smile at the nation’s office, a tan two-storey building that sits on the banks of the Fraser River. He wore a black hoodie with the nation’s crest — a woman in a red dress, arms outstretched, and the slogan “Our Land. Our Future. Our Success” — and held a can of sparkling water in a work-worn hand that spoke of a life of outdoor labour.

We chatted in the Elders’ shelter, a post-and-beam building with open sides that let in birdsong and the swish of the muddy brown Fraser River careening past on its journey to the Pacific Ocean. The shelter’s posts were tree trunks with their roots intact, splayed out like feet. As a young man, Hobart worked for a logging company run by his uncle on northwest Vancouver Island, where he helped maintain machinery. His position as elected Chief of the 300-member nation was half-time; he earned part of his living building log cabins. Wood buildings, the Chief said pointedly, could easily be constructed with second-growth trees.

After decades of logging, Spuzzum First Nation was determined to save what little old-growth forest remained in its territory. Hobart had written a letter to the provincial government calling for an end to industrial logging in the Spuzzum watershed. Too many ancestral cedar trees had been lost, along with traditional medicines that grew where their aromatic trunks rose from the earth, fertilized by thousands of years of natural decay. Large cedars, called kʷátłp, are intricately related to Spô’zêm identity and traditions.

Spotted owls, Hobart wrote, are a messenger between this world and the Spirit World: “The message of their extirpation both symbolizes and prophesizes our environmental crisis,” he told the government. The Chief questioned B.C.’s efforts to breed spotted owls while continuing to log the owls’ habitat and compared the spotted owl’s plight to the historical treatment of the Indigenous Peoples in Canada: “the registration of status Indians under the Indian Act, implementation of the reserve system, the ’60s scoop, the acculturation of Indian residential schools.”

The breeding owl pair, the Chief told us, were like the “last two of our children in that family.”

When Spô’zêm people hear or see an owl, they believe an ancestor is speaking to them. “There’s a level of excitement and there’s also a level of fear when an owl comes by,” Hobart explained. “If you’re respecting your ancestors and treating them in a good way, it could be a compliment; they’re basically patting you on the back. But at the same time, they could be there telling you to smarten up and take note of what’s happening.”

We convoyed into the lower canyon along the logging road, which bisected the wildlife habitat area where the spotted owl pair hatched their chicks. The provincial government claimed it had set aside enough habitat for 150 spotted owl pairs to survive in the wild. But even when coupled with parks and protected areas in the owls’ historic range, Foy said, the habitat wasn’t sufficient, since about half was unsuitable for the owls and parts had been logged. The spotted owl, through its demise, told us as much — if we wanted to hear.

We climbed steadily, past spindly second-growth fir and muddy patches of melting snow, until we entered the clearcuts: toppled grey stumps, upturned black earth, tangled brown roots. A wildfire of uncertain origin had charred a large patch of the habitat area, and slopes were populated by the ghostly grey skeletons of trees.

We pulled over around kilometre 10, where the valley widened like an hourglass, and stood in the mud at the edge of a precipice, gazing across the valley at the forest where the owls nested. Distant Coast Mountain peaks, iced with snow, were framed by a periwinkle-blue sky. A young, second-growth forest below us sparkled in the April sun. A pair of golden-crowned sparrows flitted in the bushes, whistling plaintively, while mourning cloak butterflies, chestnut and cream, touched down in our tire tracks and lifted off again in a timeless pirouette.

“The valley’s been logged to rat shit,” Foy observed. “But there’s something about this place that has resulted in the last pair of spotted owls being here. That’s not something any human decided. That’s something they decided.”

From our vantage point, the distant old-growth forest seemed dense and impenetrable. But below the treetops lay an open understorey with small clearings where great trees had fallen. Decaying nurse logs sprouted saplings that might one day, when they were at least two feet in diameter, conceal the type of hollow where spotted owls lay one to four white eggs. The owls often nest in “stovepipes” quilted with fir needles, where wind has knocked off the crown of an old tree, or in cavities where a large broken branch invites decay to chisel out a cubbyhole.

Northern spotted owls evolved to live in the old-growth forests of the Pacific Northwest and became dependent on them for survival, just as whales in the wild can’t live apart from the sea. The owl, a sit-and-wait predator, preys mainly on other nocturnal denizens of old growth: flying squirrels and bushy-tailed woodrats (also known as packrats). “Its strategy is to perch silently in the forest and listen intently,” biologist Richard Cannings wrote in a 2007 book, Spotted Owls, which features rare photographs by wildlife photographer Jared Hobbs. “If it hears the scratching of woodrat toenails on a log or the thwack of a flying squirrel landing on a tree trunk, it launches itself towards the sound, homing in on the prey with the accuracy of a laser-guided missile.”

Hobart turned and fixed his gaze on a fresh logging road that belted the valley’s far slope. Much of the hillside was now brown and bare. “All we can do is hope that we’ve stopped it in time.” If the logging road continued, it would soon approach the boundary of the wildlife habitat area where the owls hatched their chicks.

We followed the Chief’s SUV past a yellow excavator parked in a clearing and over a wooden logging bridge above Spuzzum Creek, bending left in a paper-clip turn. The road climbed steeply, cutting through slopes littered with fallen trees. When our passage was blocked by a two-storey cable yarder with steel guy lines — equipment used to lift logs — we parked the vehicles and walked.

The Chief, whose knee was troubling him, used a tall stick he had whittled for a staff. He picked his way silently. Western red cedar and Douglas fir trees more than two centuries old lay in piles, branches strewn about the slopes. Shaggy strips of cedar bark lined the road, providing stepping stones through the puddles and sludge. Littered around the cable yarder lay gas jugs and blue rags that had been used to wipe the grease from someone’s fingers. Sandwich wrappers poked up from melting patches of snow, not far from empty juice bottles, pulleys, cables and a rusting shovel. The Chief was not impressed. He pulled out his phone to take pictures.

Later, I learned government biologists had captured the three wild juvenile owls — two males and a female — and moved them to the breeding centre. The young female died from stress, a condition known as capture myopathy. The males, named Henry and Yoda, were matched with captive females in the hopes they would reproduce.

That left only three spotted owls in Canada’s wild — their parents and a single male who had settled in the old-growth Utzlius Valley about 20 kilometres distant. No matter how often he called, no female answered.

Adapted from ‘Signs of Life: Field Notes from the Frontlines of Extinction.’ Copyright 2024 by Sarah Cox. Reprinted by permission of Goose Lane Editions. ![]()

Read more: Books, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: