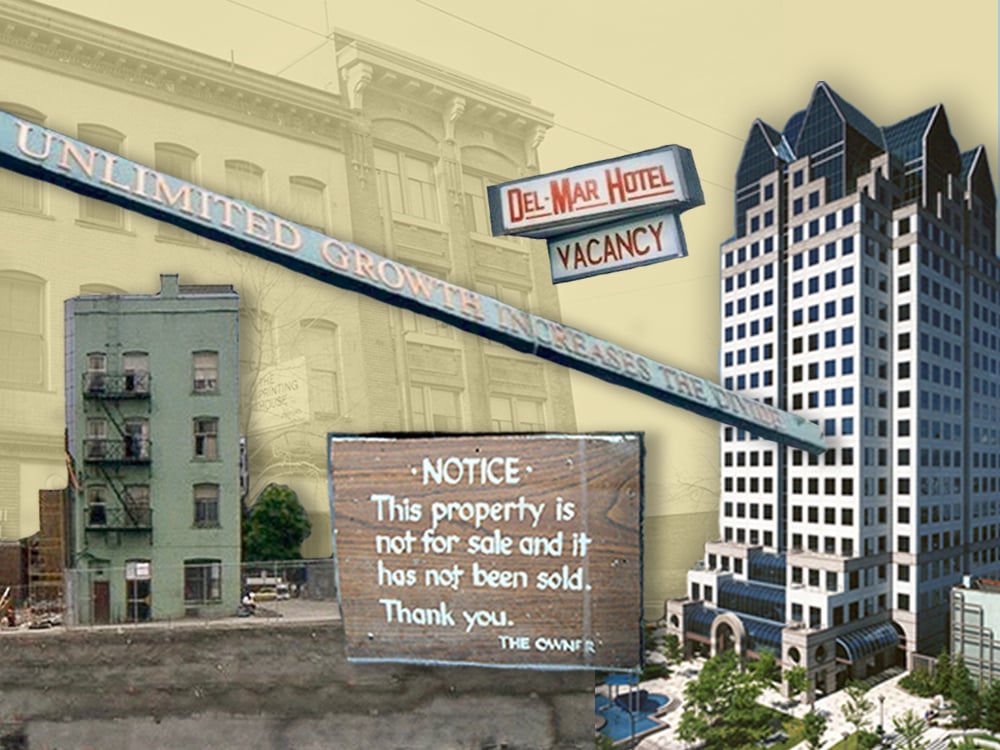

It’s a slogan that has puzzled many Vancouver residents and tourists: in seven-inch-high copper letters, appearing to match the age of the small brick hotel, it reads, “Unlimited Growth Increases the Divide.”

Maybe it has something to do with the early days of union organizing? Or perhaps this building served as the headquarters of long-ago communists?

Nope: this sign, installed in the early 1990s, refers to a more recent fight against the man.

In the 1980s, BC Hydro wanted to buy up most of the city block in order to build two office towers. George Riste, the owner of the Del Mar Hotel, refused to sell the building. So BC Hydro built just one of its giant glass and granite office towers in the 1990s. And today, the four-storey Del Mar building, located at 555 Hamilton St., perseveres.

George Riste’s son Michael says the slogan is best understood not by looking directly at the Del Mar Hotel, but by gazing across the street at the two buildings reflected in the windows of Vancouver Community College: the tiny brick hotel and BC Hydro’s office tower looming over it.

The slogan above the door of the Del Mar Hotel was created by artist Kathryn Walter in 1990.

“The little Del Mar is David, and Goliath is trying to get rid of David,” Michael Riste said. “And little David said, ‘I’m not leaving,’ and Goliath tried everything to get rid of it.”

“‘Unlimited Growth Increases the Divide’ means that if you get rid of every little single proprietorship in a city, the divide between the monopoly guys like Hydro and the little sole proprietors will become so great that the little guy can’t survive.”

Riste says the slogan continues to be relevant as small businesses in downtown Vancouver weather the pressures of the city’s notoriously pricey real estate market. He said he still gets regular phone calls from real estate agents, and every time, his answer is the same.

“I’ll say, ‘Please remove any phone numbers you have associated with me from your database,’” he said, “‘because this building is not for sale.’”

The Cadillac Coast Del Mar Hotel

The Del Mar Hotel opened in 1912 as the Cadillac Hotel, with 26 rooms. In 1944, the hotel’s name would be changed to the Coast, then later to the Del Mar. It was one of dozens of hotels built in Vancouver’s downtown in that era, some small like the Del Mar, others — like the Balmoral or the Dunsmuir — with well over 100 rooms.

At the time they were built, buildings like the Balmoral and the Dunsmuir were considered upscale. But over time, the hotels — with their small rooms and shared bathrooms — became housing for low-income people.

For the 100th anniversary of the Del Mar, Michael Riste exhaustively researched the history of the building, discovering that the hotel had been designed by an architect called W.P. White. White became known as “Seattle’s apartment builder” because of the sheer number of apartment buildings and hotels he designed in the Pacific Northwest. In Vancouver, White also designed the Sylvia Hotel, as well as several other hotels, houses and apartment buildings.

By the 1970s, some rooms at the Del Mar were still being used as nightly hotel rooms, while others had become permanent housing for working men. Today, the Del Mar provides what is essentially social housing in the private market, because Riste has committed to continuing his father’s legacy of maintaining the hotel as affordable housing. The Del Mar and other hotels like it are now known as SROs — single-room occupancies — and they have special zoning protections to prevent this low-income housing from being lost to gentrification and redevelopment.

SROs also provide important retail and restaurant space on their ground-floor levels. If you have a favourite bar or restaurant in a heritage building downtown, chances are the floors above are SRO rooms.

At the Del Mar, the retail space doesn’t house a bar or a restaurant. Since the 1960s, this space has been an art gallery, and the exterior of the building has often hosted murals.

To understand the Riste family’s devotion to this building, you have to go back to the 1930s, when George Riste was a teenager living in the small Fraser Valley town of Harrison Hot Springs.

Looking for a little excitement, “he would ride the rails into Vancouver,” Michael Riste said, “and he actually stayed at the Del Mar. And he always believed that one day if he ever had the opportunity, he would buy it.”

After serving in the Second World War, Riste married and moved to Port Alberni, where he worked in a pulp mill and bought land under a government program that provided loans to returning veterans. In 1960, Riste and his young family moved to North Vancouver, where he tried his hand at a number of jobs, from insurance salesman to warehouse worker.

Riste bought his first hotel in the mid-1960s, soon adding more hotels, houses and apartment buildings to a growing real estate portfolio. He bought the Del Mar Hotel in 1973, after the previous owner, Joe Laskey, had fallen on hard times.

Michael Riste wrote about Laskey, an amateur boxer, in his book about the history of the building, The Del Mar: Celebrating 100 Years. After purchasing the building in the 1950s, Laskey and his wife, Annie, lived in the only three-room suite in the hotel.

“Gambling on the boxing matches as a young man caused Joe to become hooked on the ponies at Hastings Park,” Riste wrote. “Unfortunately when Annie died his racing debts caused him to sell the hotels. Because of his love affair with the ponies, Joe changed the name of the hotel from the Coast to the famous Del Mar racetrack in California.”

“It’ll always remain [a gallery], even if it was to come vacant tomorrow, and people were offering all kinds of money to turn it into restaurants and bars,” Michael Riste said.

‘They would get phone calls all night long’

In the 1980s, the Ristes started to get phone calls from real estate agents with offers to sell the building. So did other property owners on the block, and one by one the other hotels were sold: the Marshall Hotel, the Hamilton and the Alcazar were all purchased and demolished.

The Ristes were the last remaining holdouts, and Michael Riste says that for years, the pressure was intense: his parents got threatening phone calls in the middle of the night and at one point had to move out of their house.

“They would get phone calls all night long,” Riste recalled, saying things like “‘You are the worst people in the world. You’re holding up progress.’”

At one point tenants of the hotel were given notices warning the building had been sold, Michael said, prompting George Riste to post notices stating, “This building is not for sale and it has not been sold by the owner.” Those signs are still displayed on the building today.

The reason for the land purchases remained secret for years, but by the late 1980s BC Hydro’s plan to build its headquarters on the Del Mar block had become public.

The loss of low-income SRO rooms in the speculative real estate rush before Expo 86 had put a spotlight on development pressures in the downtown core.

In 1990, city councillors voted to turn down BC Hydro’s request to add 50,000 square feet to the office tower in exchange for adding a daycare and office space for a recycling organization. According to a story in the Province, “council was already upset that 80 rooms in the Marshall Hotel and the Hamilton Hotel were being lost.”

“They’re displacing tenants — why not use the money to build affordable housing?” Coun. George Puil is quoted as saying in the story.

Today, the Del Mar juts awkwardly into the urban office park BC Hydro designed around its office tower, shielded by a metal screen and a row of cedar trees.

Will Woods, who runs a heritage walking tour company called Forbidden Vancouver, says the Del Mar adds life to the street.

“You can have a corporate head office, a low-income housing building and an art gallery all on the same block,” Woods said. “That was definitely not the intention of the original plan. But I think George Riste helped that block be more interesting.”

Though George Riste died in 2010 at the age of 89, Michael Riste is determined to carry on his father’s legacy at the Del Mar. The family’s real estate portfolio has shrunk over the years and the Del Mar is operated at a loss, but Riste is adamant that the building will never be sold.

“Every month we’re subsidizing that place. But that doesn’t matter,” he said. “Those people pay what they can afford. There hasn’t been a rent increase in that building, definitely since way before Expo.

“It doesn’t make sense from a real estate perspective, but that doesn’t matter. I couldn’t care less.”

* Story updated on April 9 at 1:25 p.m. to correct the name of the pictured hotel. ![]()

Read more: Housing, Urban Planning

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: