“I have a friend whose mother burned love letters from Malcolm Lowry. Gabriel García Márquez destroyed his own love letters to his wife,” reflects author and journalist Michael Harris. He is more than grateful that Farley and Claire Mowat did not make similar decisions.

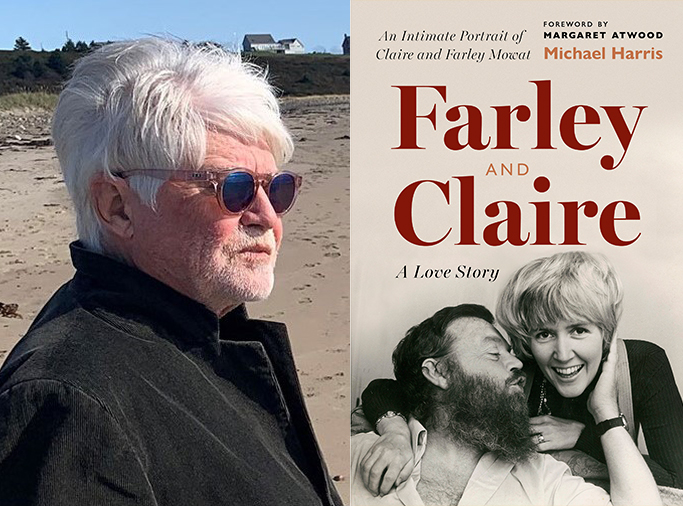

If they had, we wouldn’t have Farley and Claire: A Love Story, the engrossing new book from Greystone, published in partnership with the David Suzuki Institute, that Harris spent a half-dozen years researching and writing with the aid of his own longtime love, Lynda Harris. (An excerpt runs today on The Tyee.)

Mowat is the Canadian writer icon who first drew attention for his 1952 book People of the Deer, about Inuit hardships, and who vaulted to fame in 1963 with Never Cry Wolf, his telling of living among wolves in the Arctic that was turned into a popular Hollywood film.

Mowat was a proud environmentalist who never claimed to be a journalist. He preferred “storyteller.” As Truman Capote did with In Cold Blood in the same era, Mowat started with facts and blended and bent them into bestsellers. When a 1996 article in Saturday Night magazine created a tempest with charges Mowat invented key aspects of People of the Deer and Never Cry Wolf, he played the bushy-bearded trickster, claiming his storytelling was in service of larger truths.

So who was Farley Mowat? “Farley was a big-picture thinker with amazing perception,” Harris told The Tyee in a recent interview. “He was an original true type.” And not one to play it safe.

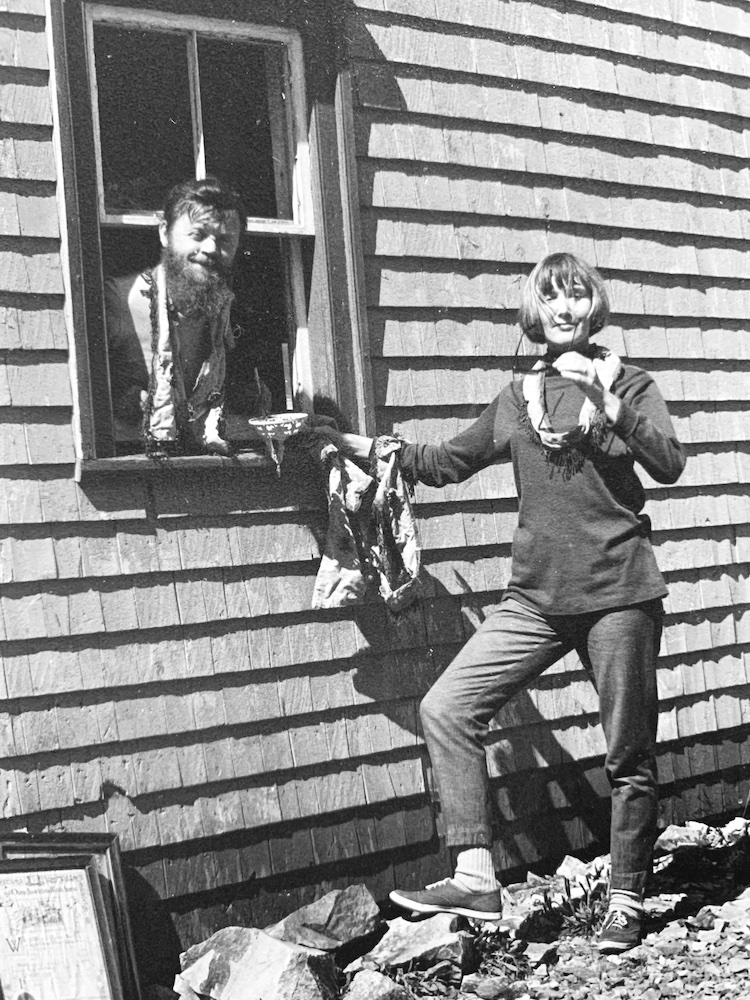

At the age of 39, a married father on the cusp of celebrity, Mowat met 27-year-old Claire Wheeler on a dock on St-Pierre Island. He fell in love and so did Wheeler, who was artistically talented in her own right and knew getting involved with Mowat meant throwing her fate to the wind on a leaky sailboat.

There’s a book because, as Harris says, “Claire Angel Mowat was brave and generous.” When Farley Mowat died in 2014, he left all his manuscripts and papers to Claire. “It was solely her decision to agree to the book and to grant us complete access to their archives and their love letters,” Harris says.

Investigations by Harris (a Tyee columnist I regularly have the pleasure of editing) have sparked four commissions of inquiry. This, his 10th book, chases a question no court can resolve: What makes two hearts match? Our conversation has been edited for brevity and clarity.

The Tyee: For people who aren’t too familiar with Farley Mowat’s work, what do you think is his special appeal?

Michael Harris: Farley was primarily a storyteller. He also had a large soul. He had a deep compassion for what he called “the Others,” creatures that had the misfortune of trying to share nature with humans.

Like the poet William Blake, Farley had the ability to see the future. He protested the Vietnam War and nuclear weapons when it was dangerous to do so. He was also passionate about Canadian independence from the U.S.

When Farley made the fateful trip to the East Coast, where he met Claire in 1960, he was under surveillance by the U.S. government. The American consul general in Toronto knew he was leaving for a 10-day vacation on the eastern seaboard, and that he owned a pleasure boat in Newfoundland. Their report, marked secret, was sent to the U.S. Embassy in Ottawa, the consulate in St. John’s and the CIA.

Mowat grew up near Toronto but gained fame by writing about the North. How did he end up there and what drew him?

A door opened in childhood when Farley made his first visit to the Arctic with his great-uncle Frank Farley, an ornithologist, to help him with a bird count. He saw the annual mass migration of the barren-land caribou for the first time, and it was one of the most profound experiences of his life.

In high school he wanted to become a professional biologist, but the war intervened. He enlisted the day after his 19th birthday. More Canadians fought and died in Italy than in France and Holland. As part of a special assault company of hand-picked volunteers, Farley scaled the cliff in a pre-dawn raid during the famous attack on Assoro in Sicily.

As an intelligence officer, in April 1945, Farley also had gone behind enemy lines in German-occupied Holland to help negotiate food drops to starving Dutch civilians. Farley reached the rank of captain.

After the carnage of the Second World War, his first impulse was to get away from modern society. He went to northern Saskatchewan, as far away from civilization as he could get.

In 1947 he joined an expedition heading into Keewatin territory to collect specimens and quickly made friends with the local inland Inuit. Two passions came together: the environment and the mistreatment of Indigenous people.

Farley was angered by the way Inuit had been treated by the establishment and was determined to become a defender in their cause.

Farley also made arrangements to be an extramural student doing fieldwork in the North. His anthropology professor was Thomas McIlwraith, head of the department at University of Toronto. Correspondence between the two men has recently come to light at the Royal Ontario Museum, where McIlwraith held a cross-appointment as keeper of ethnological collections. Mowat made many attempts to inform the government that this particular group of Inuit [Ihalmiut] were in peril. He reported that in the winter of 1946-47, five had died from starvation.

Farley’s book People of the Deer, published in 1952, focused international attention on the North — for many, for the first time. The book sparked a fiery debate in the House of Commons in 1954. Farley was labelled as “a great teller of tall tales.” Of course, in 2018, 70 years after Farley first brought attention to the plight of the Ihalmiut, they and their descendants received a $5-million settlement, and in January 2019 a formal apology for their treatment from the federal government on behalf of all Canadians.

Before he was a really famous literary figure, he met Claire Wheeler, much younger and brimming with her own talents. I found it an unlikely match, which drew me into the book — kind of like reading a mystery. I kept wondering why Wheeler tied her fate to this moody, needy, often blustery dude. What do you think these two provided each other?

It was love at first sight for Farley and Claire. Magic. She was attracted to his emotional intelligence, his wit and his words. He was unlike anyone she had ever met. Young men love with their eyes, and so do 39-year-old men. Claire was beautiful. She was also kind, perceptive and intelligent, as well as a good artist.

Farley was drawn to “the quiet one.” In private she was great fun and had a clever sense of humour. She was also ready to break out of the upper-middle-class Rosedale cocoon, and the predetermined life that would imply. Without perhaps realizing it at the time, she was an early second-wave feminist.

At the core of the book is a trove of letters between the two — fiery, frank, tortured, lusty exchanges.

I can’t think of another set of literary love letters that compare to those of Farley and Claire, certainly not in Canadian literature. They rarely dated letters, so they formed a continuous, almost stream-of-consciousness communication between them. Farley would start another letter to her sometimes as soon as he had finished putting a long letter in an envelope.

At times their letters were a lifeline — their only way of keeping any kind of contact. Farley came to know Claire best through her letters, through words. They both loved words.

So how did their letters come into your possession and what was it like to read them?

Finding and reading the love letters was one of the most amazing experiences of my life. Claire had kept Farley’s letters in Port Hope, as well as some of her journals and other things.

This project started in 2016. During an interview in River Bourgeois, Nova Scotia, Claire had mentioned there were some love letters. She invited us to her home in Port Hope in 2018, and while going through banker’s boxes of papers, Claire pointed to a particular box and said, “I think you will find what you are looking for there.” She also presented her handwritten diary of their trip to Mexico to get married. It was like finding the Holy Grail or an ancient gold treasure.

The other part of the treasure, Claire’s letters, was at the McMaster University archives, which she opened to me. Putting the letters together again was a profound experience. They were so alive with love and passion, but they were also a record of the time.

I know you work as a team with your partner, Lynda Harris. What was it like for the two of you to be “living with” Farley Mowat and Claire Wheeler for such an intensive, long project?

Lynda and I have worked on some difficult books. She has a master’s in history and does research and editing. Unholy Orders was particularly hard. The men who abused the boys at Mount Cashel orphanage were sent to B.C., where we have recently learned they allegedly continued their abuse.

Beyond the normal difficulties of every book, such as having to make large cuts you don’t want to make (I was way over the agreed word count), Farley and Claire was a joy to work on for both of us. The world certainly needs more love in these dread times.

Mowat has famously been accused of playing loose with the truth in his own narratives, which he presented as factual. What was Wheeler’s reaction to those battles and where do you think that debate has ended up?

Claire was totally on Farley’s side. Astutely, she realized the cover of Saturday Night, a caricature of Farley with a Pinocchio nose, did the damage, not the story itself, which most people didn’t actually read.

The story attempted to throw doubt on whether Farley’s accounts of wolves and starving Inuit were true. In 1948 correspondence with his professor McIlwraith, Farley reveals the starvation story was told to him by Ihalmiut who regularly visited the trading post at Windy River.

Farley wrote he had given his professor only a few highlights of the tale that went back five years “and involves a goodly number of people who should be taken off their fat backsides in comfortable chairs and given an igloo for the winter.” He told McIlwraith he was very aware that if he told the tale he would have the government and the Hudson’s Bay Company on his neck, “and it seems like rather a powerful combination.”

Farley also had access to a diary kept by a young trapper, written before Farley had even arrived at Windy River. A typescript, as well as the original handwritten diary, are in Farley’s collection at McMaster. The diary recorded evidence of starvation. Two orphaned Ihalmiut children also lived with them at the post.

We found some files in the Saturday Night fonds at the McMaster archive that indicate there may have been an attempt to discredit Farley. The fact checker on the piece later gave an interview published in the (then Ryerson, now Toronto Metropolitan University) Review of Journalism in 1999 indicating she thought the writer of the piece may have had an agenda.

The fact checker herself concluded that Mowat never claimed to be a journalist. “He said throughout the interviews he was a storyteller above all.” He was a storyteller who happened to be telling the truth, as the government apology confirms.

In this day and age we know so much about the personal lives of writers and other artists, and it can trigger public rejection. How do you think Mowat and his reputation — and book sales — would have fared in this age of constant digital scrutiny?

Farley understood marketing very well, and his antics drew attention to his books. But when Farley was given a computer by his publisher, he refused to let it in the house. He used a typewriter for all his books, as did Claire. You can still write if the power goes out. Farley saw danger in the internet. Our use of AI may prove him right. AI may lead to the extinction of humans faster than climate change.

A central “character” in the book is Mowat’s sailboat, Happy Adventure. What did that vessel signify to the couple? Was it aptly named?

Happy Adventure was their first home together, an ark, a refuge from the world. The closer they were, the better they liked it. Farley worried that possessions end up owning you. Claire loved living in simple places that made no demand on you.

At one point they started to build a beautiful modern house on a piece of land, but sold it when they realized regulations meant they would have to widen the road in, which meant taking down trees. Claire also felt the house was a little too grand for them and they would have to start worrying about what the neighbours thought.

You’re an investigative journalist. In this case you had the documents to investigate secrets of the human heart. They proved... what?

Anyone can have a fling, but to stay so much in love for a lifetime, as they did, is exceedingly rare. Tortured by injustice and seeing the natural world in decline caused by us humans, Farley could sometimes be difficult to live with. I believe he was in such despair at one point that Claire saved his life by her unconditional love. Claire understood him and did not try to change him. Their love was profound. ![]()

Read more: Books

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: