Leaving behind the dappled light of aspen forest in the Nass Valley, we climb steadily into the Coast Mountains and a dense fog. As we rise, the temperature drops, damp mist sending a chill down my spine. The road twists precariously against the mountainside. Eventually we meet a gate.

It’s exactly the kind of place you’d expect to find a ghost town.

The gate is unlocked and beyond the road dips steeply toward the coast. Glimpses of Alice Arm emerge below the cloud. After two and a half hours of skull-rattling resource roads, the gravel abruptly gives way to asphalt and we coast silently, eerily, the final hundred metres into the deserted mining town of Kitsault. Were it not for the encroaching moss, the pavement could have been laid last week.

Since its last residents left 40 years ago, Kitsault has been preserved like a mausoleum. A succession of caretakers have mowed lawns, fixed leaky roofs and changed light bulbs in an effort to keep at bay the coastal forest that threatens to consume the small settlement 800 kilometres north of Vancouver.

Kristine Eva, Kitsault’s current manager, is among the few who live here.

“I have the best job,” she says, gazing out a bank of windows in the mid-century split level that she calls home. The house, among the oldest in the community, was built for the mine manager when the original Kitsault molybdenum mine first operated, briefly, in the late 1960s. It looks out over Alice Arm, a 14-kilometre branch of Observatory Inlet north of Prince Rupert.

“I mean, look at this view,” Eva says.

When Eva says she has the “keys to the town,” she isn’t speaking metaphorically. They’re in her truck. And after taking a moment to locate them, she invites us to hop in.

As we wind down quiet streets lined with leafy maple trees, the town shows signs of careful planning. Terraced subdivisions face west, overlooking the inlet. Walking paths connect residential areas to a recreation centre — including gym, pool, racquetball courts and library — and the shopping mall. Metal-clad buildings were designed to withstand coastal weather and take in ample light during the long northern winters.

This was not just a place to work. It was a place to live.

There’s a permanence to Kitsault. The town is a relic from the days when industry was seen as a tool for “opening up the northwest” and workers came to stay. It was a place to raise a family, make friends and build a life. Hundreds thought they would do just that, relocating their life’s possessions here by boat before the road was even completed.

“The Kitsault project is an example of how mining helps build new opportunities and jobs for British Columbians,” mining company Amax of Canada Ltd. said in a Vancouver Sun ad in early 1980, as it prepared to reopen the mine. “Amax is proud to be involved in this development which will contribute significantly to the social and economic growth of this northwest British Columbia region.”

British Columbia Molybdenum Ltd. had previously operated the Kitsault mine for several years but closed it in 1972 when the price of molybdenum — a mineral used to harden steel — dropped. That should have been a warning to Amax when it bought the property in 1979 and prepared to sink hundreds of millions into developing it.

That year, Amax began expanding the townsite with roughly 300 housing units, everything from three-bedroom homes to bachelor suites. The cost to develop both the townsite and the adjacent mine, located several kilometres away, was estimated at more than $200 million.

But it was seen as a long-term investment — the mine’s molybdenum deposit was expected to last 25 years. The town would provide accommodation for its 450 workers and their families, forming a community of over 1,000 residents. The company constructed buildings meant not just to house but to gather. Multi-use complexes would host curling tournaments, swimming lessons, movie nights and quiet afternoons in the library.

Throughout 1980, as the town was under construction, Amax promoted the community in B.C.’s major dailies. The province’s newest town was “coming to life,” it proclaimed, and everything from welders to heavy-duty mechanics to a daycare manager were needed to make it run. A certified journeyman could make $12.85 an hour, $45 an hour in today’s dollars, plus benefits and vacation working at the mine, according to an ad in the Vancouver Province that fall.

“The townsite is an ideal environment for family living and opportunities to pursue year-round outdoor recreational activities,” the company said.

In addition to the recreation complex, theatre and lounge already in place, a marina was in the works to take advantage of “superb” boating and fishing. The mall would include a bank, post office, grocery store and restaurant. An elementary school was set to open in September. There wasn’t a road — yet. That would open in late 1981.

By the time the mine became fully operational in April 1981, Kitsault was already embroiled in controversy.

Its permit, issued in 1978, allowed it to discharge 12,000 tons of tailings waste — which included traces of mercury, cadmium, lead, arsenic and zinc — into Alice Arm every day. In early 1981, a report by Simon Fraser University showed traces of PCBs in mussels and cockles and sediment from the original mine. As the new mine prepared to open, the Nisga’a expressed concern about their food source and the fishery. The nation was joined by environmental groups, the United Fishermen and Allied Workers Union, the BC Medical Association and the Anglican Church.

The Times Colonist called it “one of the hottest environmental debates in recent years.”

The Nisga’a asked for a public inquiry into Amax’s plan. “What we want is an honest settlement,” tribal president James Gosnell, Sim’oogit Hleek, said, according to the Vancouver Sun. He called for a solution to the tailings issue. “Then the Nisga’a can get into it.”

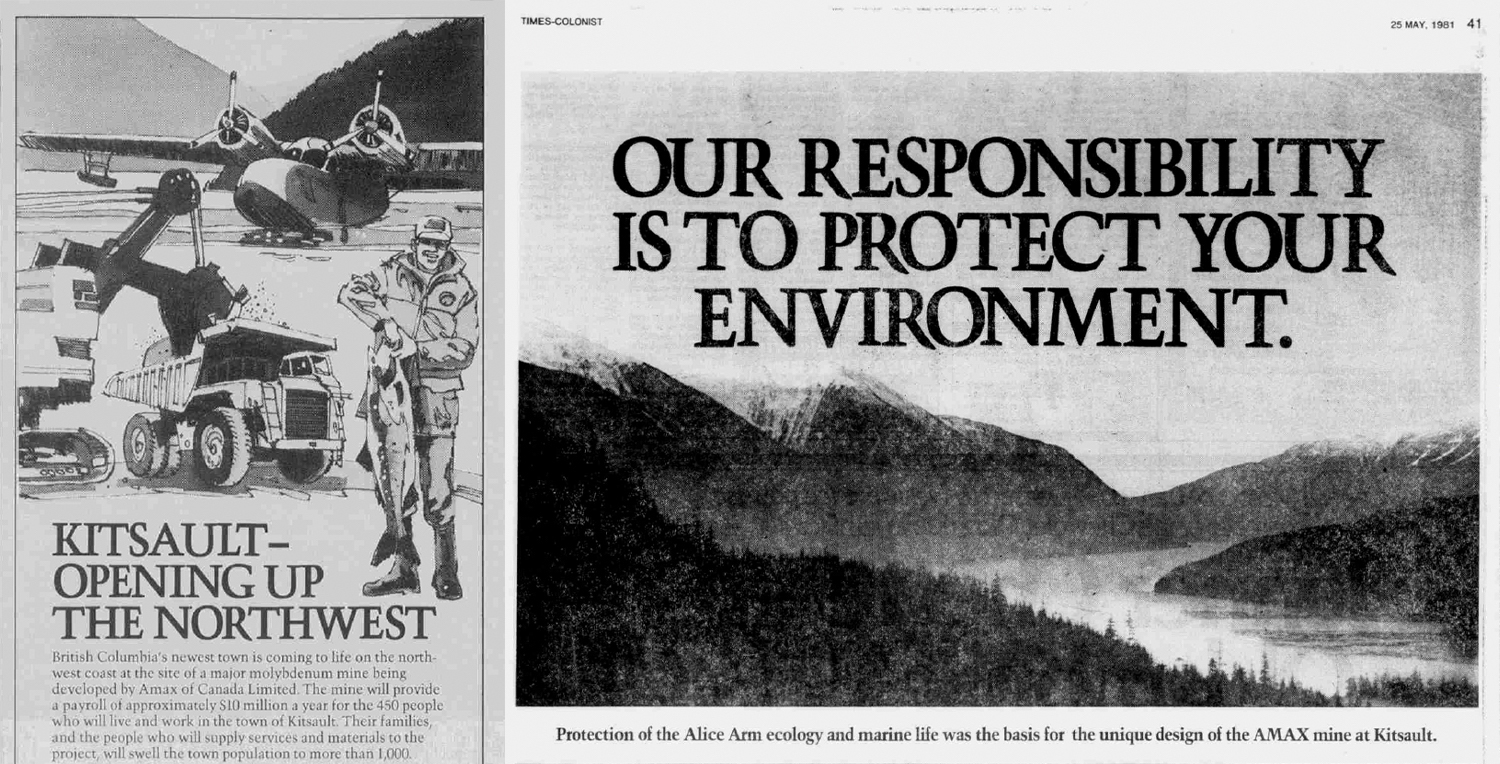

The company responded with full-page ads in the Times Colonist and Vancouver Sun showing the dramatic landscape of Alice Arm and promising to “protect your environment.” It claimed to have the most “environmentally safe tailing disposal system possible.”

An option to store tailings on land had been ruled out by the company because of the cost. Instead, the plan was to transport tailings 50 metres below the surface of the water where it would “settle downwards to the bottom of the inlet to depths of 380 metres,” the company said. The tailings were expected to collect on the ocean floor to a depth of nine to 12 metres over the mine’s lifetime.

Days after the ads ran, then-fisheries minister Roméo LeBlanc called on Amax to stop dumping mine waste into Alice Arm. Officials had spotted effluent “spewed along the shore” and a plume of suspended tailings near the water’s surface. The feds were considering fines. In the end, the mine closed for a week, then reopened.

At the same time, a federal scientific review panel was underway in Prince Rupert to reconsider the mine’s permit. In July 1981, it gave Kitsault the green light to proceed — but told the company to double the depth of its tailings pipeline, costing Amax $1 million.

Then molybdenum prices plummeted.

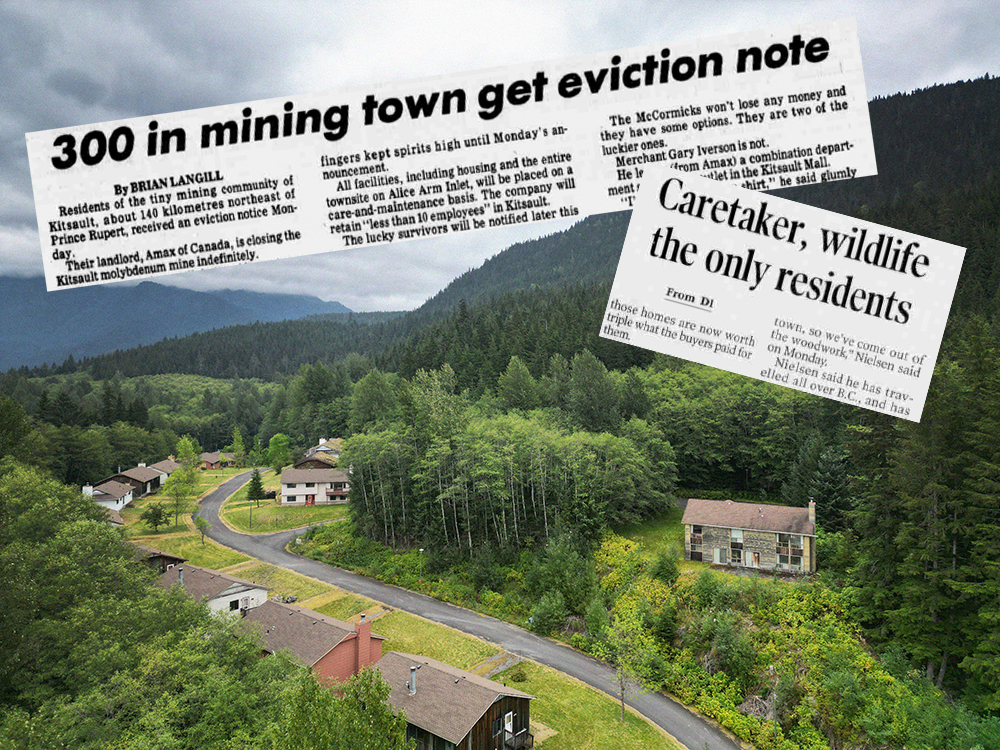

In November 1982, a year and a half after opening, Amax announced a three-month closure and hundreds of layoffs. The closure was extended into the new year. Eventually, in July 1983, remaining residents got their eviction notice. The mine was put into care and maintenance.

“We love it here,” Betty McCormick told the Vancouver Sun. She and her husband, Ben, and their three daughters were among the first to move to the community in early 1981. “It’s a great little community. It’s a shame it had to shut down.”

The McCormicks said they’d been treated fairly by the company, which was paying moving expenses. Others weren’t so lucky.

“I’m going to lose my shirt,” Gary Iverson, who operated a store in the Kitsault Mall, told the Sun.

A handful stayed on to maintain the town. In 1992, Amax tried to sell it, listing the townsite at more than $23 million. Prospective buyers balked. Then, in December 2004, after Amax’s takeover by U.S. mining company Phelps Dodge, Kitsault again went on the market, this time for a cool $7 million.

Early in 2005, it was scooped up at close to asking price by an Indian-born, Canadian-educated, U.S.-based businessman. Krishnan Suthanthiran made his money in health-care products and at first envisioned the picturesque location as a possible centre for research, recreation and the arts.

“The first thing we’ve done is try to erase the memory of a ghost town,” Suthanthiran told the Province that spring. “The town has been sitting empty for 20-plus years and we’re trying to create some excitement.”

Newly formed Kitsault Resorts Ltd. was thinking big. A university, movie studio, recreational resort and spa destination were all on the table. It could host ecotourism or wellness retreats. Paddling and hiking in the summer, skiing in the winter. Fishing and wildlife viewing. The opportunities were endless.

Then, in January 2013, Kitsault Resorts appeared to change course. It announced its plan to establish a “multi-energy” facility at the site. Kitsault Energy was born.

A floating export terminal 25 kilometres south of the townsite at Observatory Inlet, estimated to cost more than $20 billion, would export “oil, natural gas and refined petroleum products” from Alberta and northeast B.C., the company said. Kitsault would provide housing for workers.

A decade later, there’s little tangible evidence of the project moving ahead.

Suthanthiran arranged my visit to Kitsault. But I wasn’t able to pin the entrepreneur down for an interview.

Kitsault isn’t completely abandoned. A mining company doing exploration in the area rents two buildings. There’s a hum of activity surrounding the area, where workers examine rock cores under large tents and a helicopter shuttles people in and out.

Otherwise, the town is quiet.

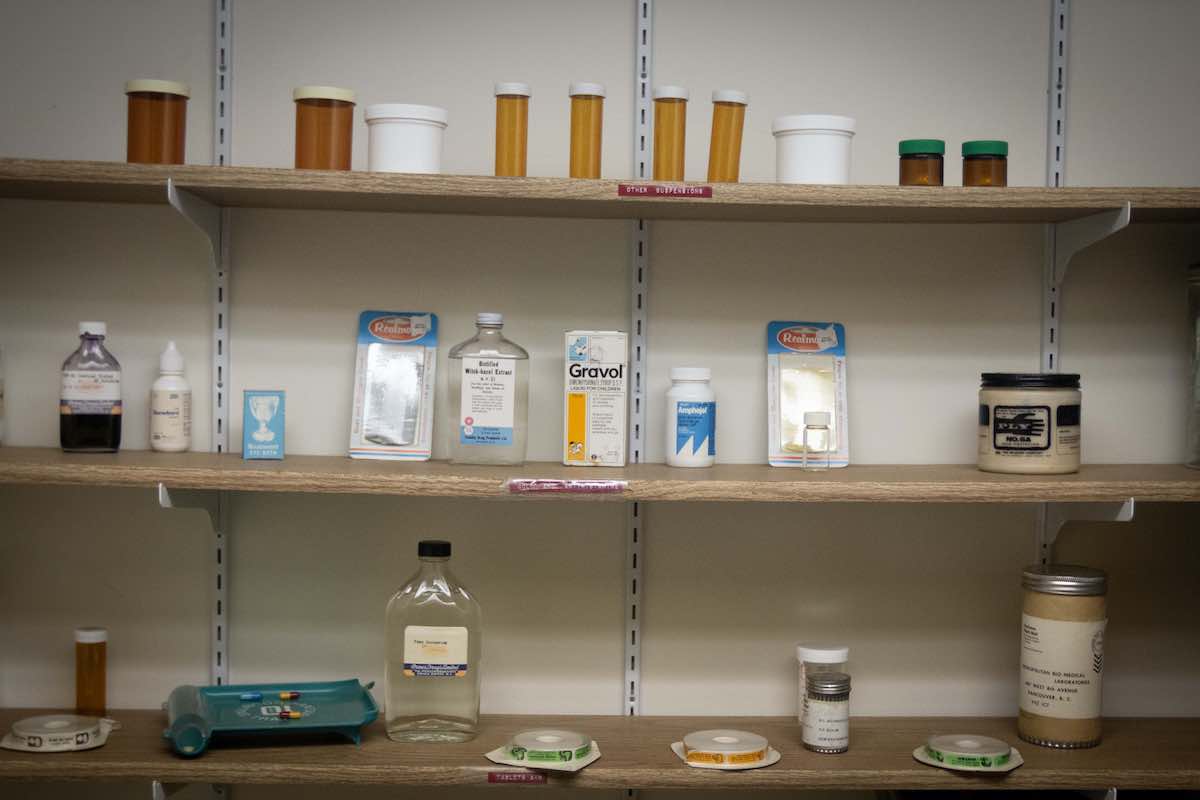

Scattered around the hospital waiting room are magazines from the 1980s, waiting for an anxious family member to thumb through articles about John Turner’s Liberal leadership race, Quebec separatism and single parenting.

In the guest house, where orange shag matches the geometric wallpaper design, neatly made beds await a visiting dentist or mines inspector. A small wet bar off the dining room and glass ashtrays on the coffee table signal it’s a place for entertaining — where a rotation of professionals brought their families and hosted guests.

In the mall, a sign on the Royal Bank counter invites you to take the “next wicket please” despite the last teller clocking out at noon on Oct. 12, 1983. If you press the pedal on the grocery store checkout turnstile, it still clunks to life, decades after the supermarket shelves were cleared of provisions.

In the Maple Leaf Pub, where Molson stubby bottles line the shelves behind the bar, there is an echo of laughter. Dozens of friends gathered here on Oct. 1, 1983, to raise one last toast to the fleeting community that was Kitsault. Then they signed their names to a document commemorating the moment and taped it to the wall, where it remains.

If there are ghosts in Kitsault, I think they must be friendly ghosts — the dreams of what the community might have been, which continue to linger. They are the hopes and plans of the people who moved here and then, two years later, packed what they could fit into their vehicles and drove off into the coastal fog. ![]()

Read more: Environment, Urban Planning

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: