- A Trillion Trees: Restoring our Forests by Trusting in Nature

- Greystone (2022)

Forests are having a bit of moment. The wildfires in Alberta and Northwest Territories; mass arrests of anti-logging protesters at Fairy Creek; Finding the Mother Tree (the bestseller by UBC forest ecologist Suzanne Simard) being used as a prop — and overarching metaphor — in Ted Lasso, the hit comedy series. It’s hard to look away.

It’s hard still to get a clear sense of what to believe about the state of the world’s forests. Our government claims that Canada is a world-leader in sustainable forestry, yet supports the pelletization of B.C.’s remaining primary forests and refuses to report on the carbon emissions of the logging industry (critics claim their levels may be close to those of Canada’s oil and gas sector).

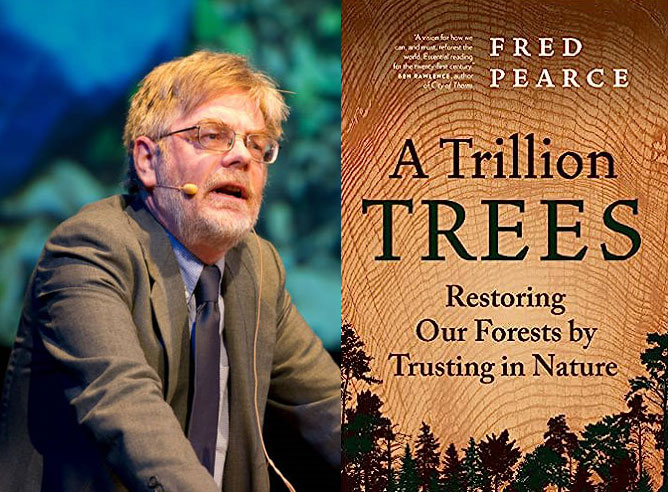

In other words, time for a book like this — an authoritative take on the state of the world’s forests and whether there’s any hope for saving them. There is, according to Fred Pearce, a British science writer who has visited woodlands all over the world in a long career researching stories for publications such as the New Scientist, the Guardian and the Washington Post.

In plain language, this fair-minded and passionate book distills a library of recent science, and first-hand reportage, to offer an update on what we now know about forests and their ecosystems worldwide, before describing what he calls “the great restoration” now underway — efforts at rewilding and establishing sustainable forest commons, managed by local people — rather than the dreadful Draxes of the world.

The opening pages provide a map of the world with over 40 forests readers will visit, from East Siberia (where forests make the wind and rain) to Rufiji (masters of mangroves, in Tanzania), to Yatir (a forest planted in the Israeli desert) and Vancouver Island (the “War in the Woods”). The narrative moves deftly then in short pithy chapters, with the vivid sense of place and keen knowledge of an Attenborough documentary.

South America and the Amazon dominate at first, as Pearce shows us the astounding biodiversity of Ecuador’s Pastaza Valley, visits a vast soy plantation on the edge of the rainforest in Mata Grosso, Brazil, and soars with a playboy-pilot in a small plane through “flying rivers” produced by the Brazilian rainforest; and climbs a tower high above the forest canopy to learn about chemicals from trees that cause rain clouds to form.

Later, Pearce summarizes recent science on the teleconnections between forests that produce flying rivers and watersheds far away. Deforestation in the Amazon, evidence suggests, would significantly alter weather patterns in parts of the western United States.

The book is full of such surprises and controversies. Pearce is not afraid to describe unpopular scientific hypotheses and has harsh words for conservationists who push for protection regardless of the cost to local communities. This is reasonable, but I found myself — someone who has cycled through clearcuts near Fairy Creek, and seen vast oil palm plantations in central Africa — resisting Pearce’s claim that, overall, the world’s forests are healthier now than in the past.

Drawing on science based on satellite imagery, coupled with historical literature, he notes that forests have come back significantly over the last century, owing in large part to the exodus of rural residents to cities — in New England, for example; and, in parts of Africa, owing to private land management. Here he points to faulty measurements by commercial foresters and conservationists alike, who tend not to count trees on farms and semi-arid parts of the continent. According to researchers at the Stockholm Environmental Institute a third of the trees in Kenya and Uganda are on farms, often in clumps not big enough to show up on satellite images.

The science on measuring forest cover is hotly disputed. And, it turns out, the controversy over the state of forests is nowhere more heated than in Canada. Pearce therefore dives deeply into assessing the claims and counter-claims being made here. Canada has almost a 10th of the world’s forests, including over 300 million hectares, in a belt around 110 kilometres wide between the treeless tundra and warmer, more arable lands to the south. Often the trees are in big blocks, undisturbed by roads, mines, pipelines and other development, which has won Canada the second highest score for “forest landscape integrity,” just after Russia, from the Wildlife Conservation Society.

But as environmental groups point out, each year a million acres of boreal forest are logged, and Canada is responsible for “the greatest total loss, acreage-wise of primary forest in the world.” Pearce draws from the federal government’s website devoted to “debunking deforestation myths,” which points out that “despite media claims, harvesting, forest fires and insect infestations do not constitute deforestation… since affected areas will grow back.” Some trees will be replanted, others will regrow naturally. This is not, he argues, the ecological disaster that is unfolding in parts of the Amazon basin, where vast tracts of land are being cleared to grow soy and raise cattle. Still the government’s myth-busting is also deceptive as forest cover is an extraordinarily incomplete measure of forest health.

Roads and clearcuts have broken up most of the largest blocks of pristine forest, harming wildlife, and opening up them up to miners, hunters and developers. Government claims that clearcuts mimic the effects of forest fires are bogus, the author says, and he quotes Suzanne Simard whose research shows that clearcutting dismantles subterranean fungal networks that sustain forests and that replanted trees may lack these support networks.

“What is happening in Canada’s great forests may not be widespread deforestation, but it is certainly substantial forest degeneration,” Pearce concludes.

The second half of the book focuses on the restoration of forests now underway and provides evidence for the claim that replanting of forests is often less successful that simply letting nature do the work. This is not to say that replanting is pointless. The regreening of Europe, whose forest cover bottomed out in 1850, has been done through a mix of replanting and nature taking its course. The author notes that the loss of the continent’s old-growth forests, and replanting with a limited variety of marketable trees, has led to a serious decline in biodiversity and disease, but he argues that Europe’s forest recovery is well underway and the new forests will mature in time to become future “old-growth” forests.

Europe’s recently announced “Green Deal” promises to grow Europe’s forest cover by a further three billion trees by 2030, and Germany’s agriculture minister has stated that “every missing tree is a missing comrade-in-arms against climate change.” The debate now is over how to allow forests to regenerate: aided by planting or natural regeneration — “letting nature rip.”

Most hopeful, however, are programs that return land to Indigenous communities, letting them manage their resources and not just for environmental ends. Indigenous land preserves in the Amazon, for example, which cover an area the size of England and employ an estimated 70,000 people tapping wild rubber and harvesting nuts and palms, while protecting the forest better than in state-protected areas. Or the community forest managed by the Xaxli’p people in the Fountain Valley near Lillooet, B.C. Here the emphasis has been on managing the forest for “ecological and cultural sustainability” — restoring clearcuts and stands of trees that are overly dense owing to decades of fire suppression.

“The evidence is that Indigenous and other forest communities are the best conservers of threatened forests and will be the best nurturers of the new forests,” Pearce concludes. “They know them best and need them most.” ![]()

Read more: Books, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: