[Editor’s note: This excerpt forms part of our spotlight on B.C.’s literary magazines. Today, we republish a piece by Felix Wong, originally published in PRISM international. PRISM, founded in 1959, is Western Canada’s oldest literary magazine. It focuses on bringing together emerging and established voices, and has published everyone from Michael Ondaatje and Evelyn Lau to Gabriel García Márquez and Jorge Luis Borges. PRISM’s prose editor Vivian Li says of Wong’s piece, originally titled “Shall We Talk,” “Felix Wong's piece, filled with gentle interweaving and vivid paragraphs, repeatedly draws me in with its honest and complex portrayal of an event that impacted his family’s history, but which had been largely left unspoken. The search for answers with regards to his aunt and the tragic Lauda Air Flight 004 plane crash parallels a personal journey that is both honest and visceral.]

Four hours from Bangkok, deep in a forest where towering stalks of bamboo grow unchecked, stands a sign with the words, “Falled Aeroplaned Point.” Hunks of broken metal dot the vicinity, deformed from decades in the elements. One piece, larger and angular, looks like a rudder, though I can’t be sure. A row of red and green shrines sits nearby. The driver tells me they were erected by local villagers to placate the lingering spirits of the victims. This should be a chill-inducing scene, but that’s not how I feel standing here.

In fact, I’m having trouble feeling much at all.

In May 1991, shortly following a routine stopover in Bangkok, Lauda Air Flight 004 broke apart mid-flight, raining cargo, metal, jet fuel and human bodies over what is now Phu Toei National Park. The cause was later attributed to a mechanical failure, which resulted in the deployment of an engine’s thrust reverser. All 223 passengers and crew were killed in what remains Thailand’s deadliest aviation incident to date. My Aunt Cloud and her husband, enroute to their honeymoon, were among them.

“So, how do you feel?”

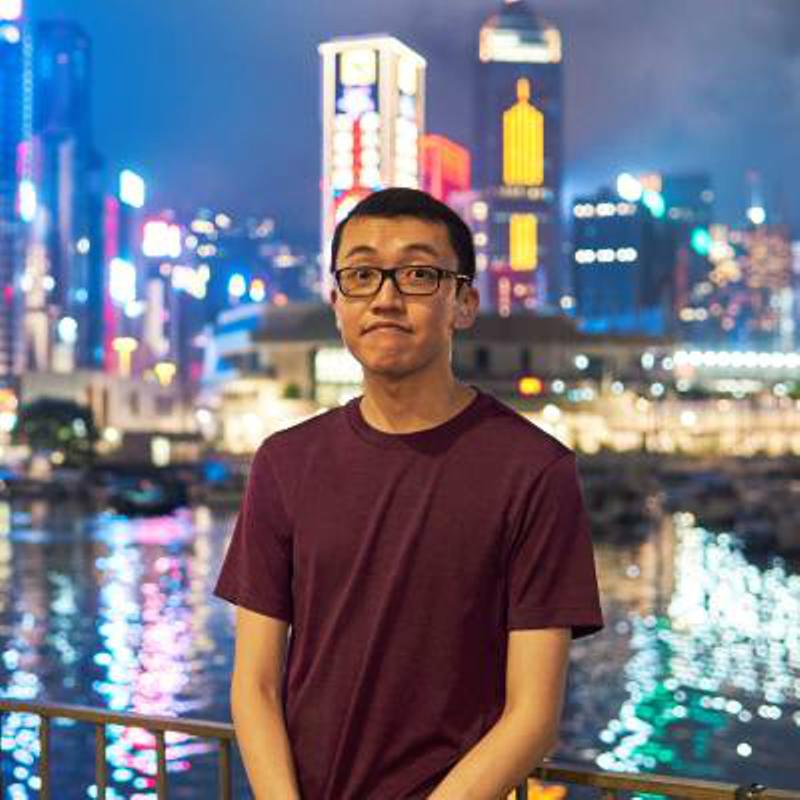

Illyas glances at me. He needs quotes for the South China Morning Post. He wants to know why a 25-year-old would willingly venture halfway around the world to pay respects to an aunt he has never met. I don’t tell him I’m struggling with the same question myself. (The Tyee is using a pseudonym for Illyas to protect his privacy.)

I could lie and come up with something print-worthy, but I owe Illyas the truth. “I feel nothing,” I tell him for the third time this afternoon. I don’t know who is more disappointed by my response.

When Illyas goes to photograph the site, an unexpected feeling creeps over me. Awkwardness. I am itchy and uncomfortable in my own skin, like I don’t belong. The faces around me, Illyas, his translator, and the two drivers we hired, show a mixture of excitement, sorrow and apprehension. How is it possible I feel none of that?

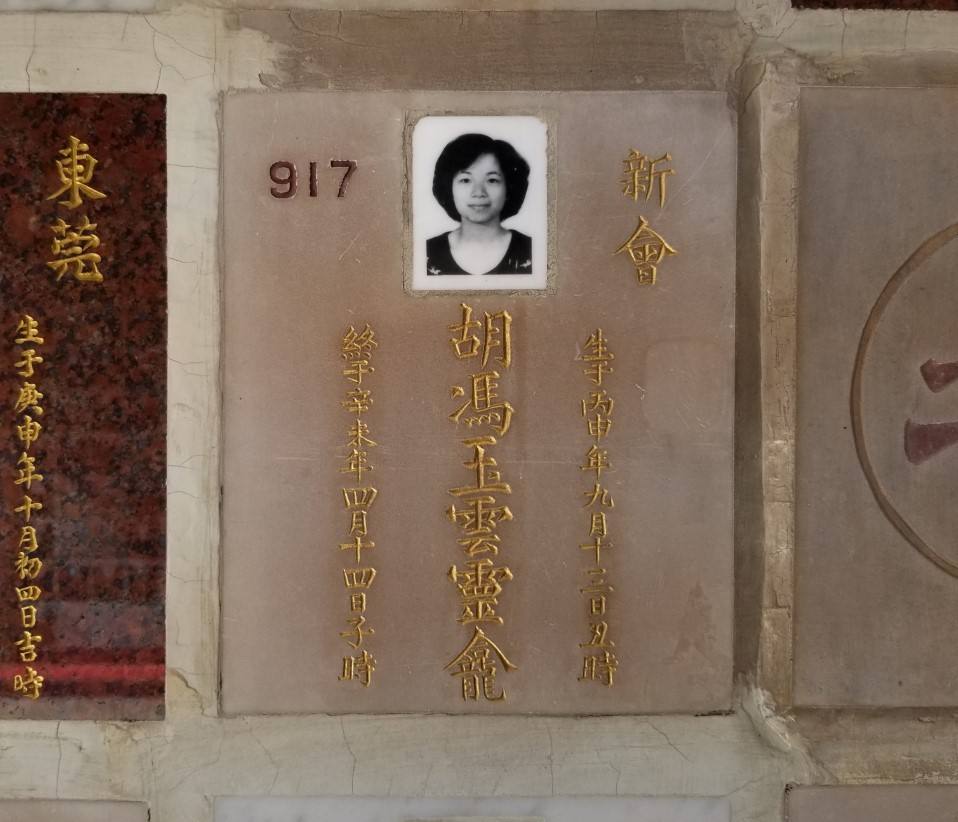

Most of what I knew about my Aunt Cloud was gleaned from her columbarium plaque during tomb-sweeping visits. Her name, her face (round cheeks and frizzy hair, like my mom), that she died a few years before I was born, and that she was only in her 30s when it happened. My mom and her seven siblings never spoke a word about Cloud, besides that “she died in a plane crash” — the same story told to everybody in my generation.

Chinese people have an unwritten rule: we don’t talk about the dead. Whether this rule contributes to my lack of feeling at the crash site, I cannot concretely say. I do know it’s allowed the surviving siblings to forget.

I didn’t learn the details of my aunt’s death until last summer. A visiting uncle from Hong Kong had one too many beers over dinner and surprised us all by suddenly bringing up the plane crash. He and my mom were tasked with retrieving Cloud’s body from Thailand back in 1991. This was, I later learned, the first time in 28 years that any of the siblings had openly discussed the incident. As they spoke, it became apparent they had vastly different recollections of the trip.

“We were kept at the hotel in Bangkok and told to wait for news,” my mom insisted. “We weren’t allowed outside or anywhere near the crash site.”

“We did go, you just don’t remember.” My uncle laughed, too loud, too hard. He slid me a beer, then cracked open another for himself. “Tell me, Felix, why would they lock us inside the hotel?”

Later, my uncle said, “All the bodies were mangled beyond recognition. We couldn’t identify her.”

“Of course we did. Using dental records. We brought back her ashes.”

“That was on the second visit. We had to go to Bangkok twice.”

“You’re crazy.” My mom shook her head. “We went once.”

My uncle and my mom argued back and forth until they could no longer ignore it — the realization that they were both unreliable narrators of our shared family history.

“Wait,” I said, struggling to piece together the information. “You’re telling me there were more than a few bodies?” I had assumed this was a small accident, one involving a seaplane or glider.

My uncle turned to me. “Two hundred.”

I couldn’t sleep that night. How could someone misremember an experience as traumatic as losing a sibling? Why was this my first time hearing about the crash? Why had no one shared the details sooner? Restless, I rolled out of bed and began to scour the web for answers. They came immediately.

Lauda Air Flight 004. I had read about the incident years ago in a Niki Lauda biography. Lauda, a famous Formula One driver and owner of Lauda Air, played a major role in the investigation, forcing Boeing to admit fault and install additional safety features so such a catastrophe would never happen again. It didn’t occur to me that my family paid a price for this victory.

My searches eventually led me to a decade-old blog post by a British expat. Stephen wrote about his camping trip to the national park in Suphan Buri province, the crash site of Flight 004. The blog hadn’t been updated in years, but I sent an email anyway, asking for directions. I received a reply within the hour, along with a phone number.

In our video call, Stephen told me the debris was still there, almost 30 years later. “Suphan Buri never forgot,” he said with a shrug. He suggested I visit the crash site to see for myself.

That same night, Stephen introduced me to Illyas, a reporter in Thailand. In exchange for permission to write an article on Cloud and me, Illyas would take me to the crash site.

My mom decided she couldn’t accompany me to Thailand. She was swamped with work. Nor would her siblings, none of whom were interested in reliving the past. I had to go alone.

I’ve been asking myself if I keep secrets. If I, like my mom and my uncle, have repressed anything. Of course, there’s my internet browsing history and questionable cryptocurrency purchases. And my Grade 11 camping trip, when my lactose intolerance kicked in an hour’s hike away from the campground. But generally, I’m an open book. Ask me a personal question, and I’d tell you the answer.

I’d tell you about how the last good day I can recall was a Thursday in my final year of high school. Nothing of note occurred, but I remember waking up feeling completely free of tiredness for the first and only time in my life. I didn’t linger a moment longer in bed. I got up and got on with school. That strange energy powered me through the entire day. I wondered if this was how others felt all the time, the straight-A students, the teachers who beamed in the school hallways. The next morning, I was disappointed to find I was back to my usual self. Life felt neither good nor bad, but neutral. I had taken a melatonin pill the night before the good day, which I thought must’ve been the cause. Though I’ve tried since, I have never been able to replicate that same feeling.

I’d tell you that the last time I cried was not at the crash site, but four years earlier on a park bench, with a high school friend beside me offering support in the form of a shoulder. My first love, an American I had met in Hong Kong, arrived in Vancouver unannounced. Having spent the better part of two years trying to win her back, I was convinced that this time, she’d be trying to win me back. I was wrong.

I’d tell you I think something in me broke long ago, and I can’t say with certainty when.

“Ha, ‘I don’t know how,’” Illyas imitates my response at the crash site, after he asked if I wanted to perform traditional Chinese ancestor worship rituals. “Can you believe this guy? Even the driver came prepared.”

We’re in a cafe back in the city, laughing about the whole ordeal.

“That’s actually pretty funny,” I say. It really was. Our driver had packed yellow flowers and incense sticks. He had recently won the underground lottery by playing 223 — the number of lives lost in the crash. The driver wanted to thank the spirits, and more importantly, divine another winning number.

“But it’s true,” I tell Illyas. “I don’t know our rituals. I was never taught.”

I explain that in Chinese culture, we burn joss paper for the dead. Joss paper comes in myriad varieties: hell money, gold and silver, clothing, reincarnation money, charms and replicas of everyday items, like iPhones and designer handbags. When burned, these papers are thought to materialize as useable objects in the underworld. The difficulty lies in knowing what to burn on a given occasion. Some papers are reserved for kin, some for the gods, others for wandering ghosts. In our family, only my mom’s eldest sister understands the ins-and-outs of the practice, and she has never tried to pass on this knowledge to anyone else.

“But I don’t really believe in that stuff. How can something be transported — intact, no less — across the realms of the living and the dead? It’s not like 3D printing,” I joke. Though in hindsight, part of me wishes I had burned something for my aunt. Just in case.

Finished with the coffees, Illyas and I explore a nearby outdoor market. I’m surprised to find a full-sized bomber plane ornamenting the eating area. In green and brown camouflage paint, it rests on a raised platform, hovering precariously over a dozen seated picnic tables. Tourists and locals smile for photos with the bomber. I snap one too and we move on.

After the plane crash, my relatives rounded up Cloud’s possessions and dumped them into a bonfire, so they could be returned to her in the afterlife. Whatever survived was kept in an unmarked steel chest, now buried under houseware boxes and plastic tubs in our ancestral home in Hong Kong. I am the first to peek inside in 28 years.

In the chest, I find dozens of neatly annotated photo albums documenting Cloud’s travels. China, Taiwan, Thailand, France, Switzerland and others. She saw more of the world than I have. I’m impressed. Doubly so when I consider the time in which she lived. Cloud was a psychiatric nurse, one of the better-paid professions in the ‘80s, but she was described by one of my uncles as someone who “for every $10 earned, would send home $7, maybe eight.” Her generosity funded my mom through university and put food on the family table. I have no idea how she scraped together enough money for her trips.

Among the albums and hundreds of legal documents from the two-year-long case against Lauda Air and Boeing, I find a letter. It’s from a Thai temple, notifying my grandma that the Thai authorities had identified and cremated my Aunt Cloud on Aug. 23, 1991 — two months after my mom had returned from Bangkok with Cloud’s ashes.

My mom waves off the letter as a mistake. “Maybe they printed a random date, for formality purposes.”

“Ma,” I say on the phone, “It’s date-stamped by the embassy.” I send a picture of the letter so she can see the government seal.

She doesn’t speak for a moment. “Then what did I bring home?”

None of the other seven siblings were aware of this letter’s existence. Grandma couldn’t read English; she wouldn’t have understood the letter on her own. My relatives say she must have discounted it as just another legal document and stashed it away. The existence of the letter means the urn inside Cloud’s niche might not contain her ashes after all. The only person to know for certain would be my grandma. She died 15 years ago.

There is the thing with my father.

Because I don’t mention him, people tend to assume he’s either dead or long gone. And I admit, it’s easier to let them think that than to explain. How in my first week as an immigrant in Vancouver, I had befriended a boy at the neighbourhood Chinese restaurant. Our families had become intertwined thanks to this friendship. His mother had been single.

My mom pulled me aside one weekend evening, after my father had gone out. I was nine years old. “You understand where he is going, yes?” she asked, gently.

I nodded.

“One day, you may have to choose. Me or him.”

That day never came. It took years before I grasped the impact of my father’s infidelity, and longer to decide how I would treat him. By the time he stopped leaving at night, I had already acclimated to life without a father figure. Though we’ve always lived under the same roof, my father and I have not exchanged a word in over a decade.

When I ask my relatives why we don’t talk about the dead, they cannot answer confidently. The query is met with puzzlement every time. Many of them say it brings “bad luck,” although no one has managed to explain how or why.

“Because you never asked,” my mother says.

“Talking brings back unhappy memories,” one aunt suggests.

Another says it’s because Cloud died a “wrongful death,” a Chinese term for any death by unnatural means, such as suicide, war or accident.

Perhaps my dentist in Vancouver gave the most telling response. Over the course of a filling, I mentioned my bewilderment at how it had taken 25 years before I learned about Cloud, and casually posed the same question: why don’t Chinese people talk about the dead?

She sat back and, narrowing her brows, said, “We just don’t.”

“You know how hard it is to find an urn space in Hong Kong? Everything is allocated years and years in advance. You take whatever you get,” says my uncle, the one who previously visited us in Vancouver. “That’s why your grandma’s ashes are kept on the opposite end of the city from Cloud’s.”

We’re in his van, chugging up a long, windy road toward the seaside columbarium that houses Grandma. A retired taxi driver, my uncle knows this route by heart. Before the completion of a walking trail last year, the only way up was by car. Whenever a fare brought him there, he would park his car and spend a few minutes wiping down Grandma’s plaque with tissues and water. As we round a corner and lines of tombstones come into view, my uncle says something I have never heard anyone say.

“When I die,” he tells me, “scatter me into the ocean.”

Caught off-guard by his sudden request, I ask him to repeat himself.

“I’m saying, I don’t want you driving up a damn mountain for me. Don’t burn anything, don’t visit over Chinese New Year or Tomb-Sweeping Day. Let these traditions die with us. Just pick up a photograph once in a while and think of me. That’ll be enough.”

Weeks later, my uncle is rushed to the hospital for emergency heart surgery, shocking everyone in the family. He’s the second youngest of the siblings and by far the most active. Hearing this, I can’t help but wonder if our conversation jinxed him.

Unless I’m misremembering, I was 12 when my father and I last spoke.

The two of us stood on the shore of English Bay, watching the sun bend to the horizon. At this point, we were already strangers. He seemed to notice my unease and asked, uncharacteristically, “What is it?”

I avoided his gaze and swirled my foot over the sand, drawing circles in the coarse grains.

“Are you having trouble at school?”

I wasn’t. But I nodded anyway.

“Trouble with school friends?” he probed. Then he said, “I see.”

Silence fell over us as usual. Wanting, just for once, to see what we would be like without the silence, I asked, “Have you ever had that?”

“Trouble with friends? Of course. Tons of times.”

“How did you fix it?”

“Well,” he said, scratching his head, “if I did wrong, I’d apologize. Admit my fault. And hope they forgive me.”

“Did they?”

“Not always.” He turned to me. “But you don’t have to worry about that. At your age, whatever misunderstanding you have with your friends, I’m sure it’ll pass.”

The silence returned. Yet we lingered, basking in the dying sunlight. Looking back, I think we both understood we would not share another moment like this.

“Some bodies from the crash were burned beyond recognition, like this,” Dr. Leung says, pointing to his screen. Grotesque images stare back. I can’t tell what I’m looking at. Blackened flesh. Bones. “The rest had rotted by the time we arrived. The Thai authorities kept them in a parking lot, out in the open. You know the climate there.”

We’re in the operating room of Dr. Leung’s dental clinic, a few buildings down from a tutoring centre where I once worked. It’s very likely I have passed this man on the street, oblivious to our mutual history.

As a forensic dentist, Dr. Leung has helped solve some of Hong Kong’s most high-profile murders, hence his recent cameo role in the local drama series Forensic Heroes IV. My taxi driver uncle caught the airing and immediately recognized the face on his television. The face of the man who identified my aunt.

“We don’t release bodies unless we’re a hundred percent certain. Of course, during cremation, bits of other people’s DNA are bound to get mixed in, but that’s another matter,” Dr. Leung says.

“It’s just that my family received this.” I pull up the embassy letter on my phone. “In August.”

“That’s right. We identified only a small portion of the bodies initially. I had to fly back to Bangkok again in August to identify the rest.”

“But this doesn’t make sense, because my family retrieved the ashes in June.”

Dr. Leung thinks for a moment.

“Could this mean we have someone else’s ashes?” I ask.

“We only handled the forensics. Thai authorities took care of the logistics... but I don’t think they would mess this up.” Perhaps sensing my skepticism, he adds, “I’m not sure how you could find out anyway.”

I sigh. He’s right. DNA testing on ashes is problematic enough without also having to persuade my aunts and uncles to allow for the ashes to be disturbed.

As I leave, I pause to ask, “Why do you think Chinese people don’t talk about the dead?”

“Simple. Fear of ghosts.”

“Superstition then?”

“Some believe mentioning the dead will bring their spirits. I think it’s silly. It’s your own family. Even if they’re now ghosts, why should you be afraid?”

I once wrote a screenplay about the rise and fall of a Chinese restaurant in Vancouver. The overall story loosely follows my family’s immigration experience. A father cheats and the son must reckon with the consequences.

My writing peers found their relationship unrealistic.

“I just don’t get it. How is it possible they can live in the same house all these years and not talk?”

“Exactly. At some point, you’d think they’d use their words and hash it out.”

I stayed quiet. I didn’t mention the characters’ real-life inspiration.

The morning after I fired off the screenplay to a writing competition, I woke up to a notification in my inbox. A new friend request. From the boy, the one I befriended, whose family owned the Chinese restaurant. Over 10 years had passed since I last saw him, yet his face remained the same, just slightly pudgier. I still don’t know why he chose that day to reach out.

I had summoned a ghost.

The summer before I started university, I stood in the kitchen, waiting for the frying pan to heat up. My father had the day off work. He passed by and said something I can’t recall. I ignored him, as I had become used to doing. He must have decided that was his last straw.

I kept my back to him as he yelled. I remember the words, “You’re garbage.” And I remember a fraction of a second, when the glowing red of the stove element seemed so enticing, and I thought, I can just grab this hot pan, turn around, and swing.

I snapped off the stove and ran to my room. My father followed and cornered me. There was no way out but through him, so with years of anger and guilt in my veins, I threw an elbow.

My father didn’t react, perhaps out of sheer surprise. He stared at me, my elbow still glued to his cheek. His eyes seemed to soften. Capitalizing on his state, I pushed past him.

I caught the first bus I could and rode it straight to the terminus. Eager for more distance, I followed the road, and walked, and walked. Somehow, I found myself back at English Bay. As I watched couples stroll by and children wade out into the ocean, it dawned on me that I wasn’t afraid of my father, but rather myself and what I might be capable of. I was relieved when my adrenaline gave way to fatigue.

On my return home three days later, my parents were happy not to speak of the run-in. They made it easy for me to pretend nothing had changed. So I too adopted this silence.

For a long time, whenever I was reminded of my father, I would relive that day’s rage. I’d swallow that rage and do my best to keep it down, far away from the eyes of friends and family. Now, when I think of him, I feel nothing. I wonder if it’s because enough time has passed. Or is it because I don’t talk about it?

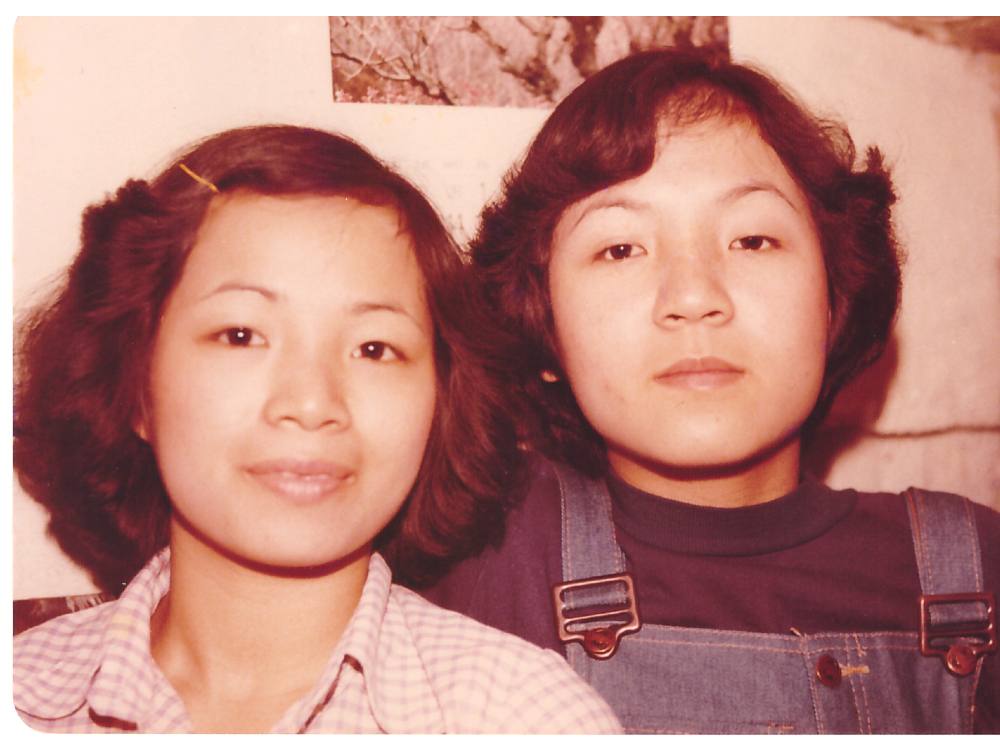

I worry about how my relatives will take Illyas’s article. I had let them know in advance there would be a story in the paper and that it would be a full page, but I forgot to mention the photograph. It’s a close-up of Cloud and my mom, snapped in their 20s, sporting their signature wavy, neck-length hair and smiling faintly into the camera. I buy enough copies for the family anyway.

Each and every one of my aunts and uncles nods and folds up the newspaper, promising to read it later. They don’t ask about my experience or the crash site. They don’t show surprise, sadness, happiness or anything. Maybe this runs in our blood. I have no way of telling if they approve of what I’ve done, and I don’t have the courage to ask.

On the other hand, the relatives in my generation leave likes and comments. One cousin posts that she cried upon seeing Cloud’s picture. Another thanks me for taking the time to pay respects. Over a cigarette, my younger cousin by a year — normally a reserved guy who steers clear of family matters — tells me, “You have heart.”

I say I didn’t do it for anyone. I did it to get answers. For myself.

“No,” he says, blowing out smoke from his nose. “You have heart.” ![]()

Read more: Media

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: