It is hard to contain the covetous, practically lustful feelings aroused by the Vancouver Art Gallery’s newest exhibition Cabin Fever.

Organized by guest curator Jennifer M. Volland, senior curator Bruce Grenville and associate curator Stephanie Rebick, this is a major show wadded full with ideas, installations, images, objects and cultural associations from the highest of auteurs (oh, hello, James Benning!) to the curdled gross-out of Sam Raimi’s infamous rural romp The Evil Dead, wherein demons meet the long arm of chainsaw justice.

The list of artists, architects and, yes, products represented in the exhibition is exhaustive — from Benning to Frank Lloyd Wright, but it barely indicates the depth of what is on offer. There are summer cabins, winter chalets, cabins underground, cabins perched on cliffs — every possible permutation — rustic, sleek, homespun, high tech. Some are made of crap, and some are so exquisite that you may feel weak in the knees. Cabin, take me away!

But perhaps the most startling aspect of the show, despite its breadth, is how deeply personal it feels.

In a recent walkthrough with co-curator Volland, a flood of associations came tumbling out of the woodwork — Waldenian visions of quiet, contemplative spaces where your thoughts could gently unfurl and untangle themselves from the jangly noise of the outside world. As angst falls away, a vision of a better, more thoughtful life emerges. Even if this is a fantasy, it is an exceedingly powerful one that has continued to evolve as humans have become evermore disconnected from the physical world.

The show is divided into three sections — Shelter, Utopia, and Porn — with a fair amount of bleed between the three. As Volland explains, there was such a wealth of content that, “We could have just kept going and going.”

For every person on the planet there is apparently a cabin — be they a writer, artist or Unabomber. Ted Kaczynski’s infamous abode is the first thing to greet visitors in the exhibition. It is a curious choice and establishes the nature of the show with a bang, one might say. Far from being a romantic dappled retreat for moony souls looking to write poems to a pond, there is a darker side to cabin life. From its use as a colonialist land grab, a hidey hole for dark doings and of course, a setting for many horror films. Cabin Fever includes a recreation of a classic horror film setup, a rustic retreat, a flickering television set, and crepuscular darkness curling in at the edges.

But despite a commitment to detailing the more problematic aspects of cabin history, the predominant theme is still deeply romantic. Perhaps it is inescapable, the allure of the thing, the powerful pull of solitude, peace, self-containment and to be perfectly blunt, lust. These things are horny-making, hence the show’s final section Porn, dedicated to the nature of desire that cabins inspire, or, maybe more correctly, the desire for nature. Authentic, genuine, rough and tough — all of the qualities that cabins represent are commodified, airbrushed, fetishized and sold to a public eager for idealized images. Websites like Cabin Porn may be the nadir of this impulse, but it has been around for a long while, fueling political and social aims from a broad array of different folk.

As Volland writes in an essay in the show’s catalogue, the idea came from a very personal impulse — namely the construction of her family’s cabin in Three Rivers, California. It is an eloquent and thoughtful piece that delineates not only the major themes and influences of the exhibition, but also the funny and, occasionally, unconscious ideations that manifest in the right clothes, the right furnishings, the just so knick-knacks that spell out the correct form of cabin life.

Almost everyone has a cabin concept in their mind, a place to run to when the world becomes too much. It wends its way through contemporary culture with an aspirational knife edge. One gallery wall is dedicated to American Heritage brands like Pendleton and Filson as well as Canadian newcomers like Roots, all promising well-worn experience in red checks and warm brown leather. This very human yearning has been utilized not only as a sales tool (everything from Lincoln logs to backpackers’ perfume) but has also been exploited by corporations seeking to humanize the workplace. Vancouver’s Hootsuite designed its headquarters to resemble a log cabin, complete with cots and assorted bits of random wood, to combat urban angst.

As someone who grew up in cabin country, I can tell you that rural life is not all it’s cracked up to be. Yes, it’s beautiful, but it’s also lonely, dreary and stultifyingly dull. Not to mention teeming with bugs. In the log house of my Kootenay childhood, every season of the year brought a new insect invasion. Cluster flies blackened the windows in the spring. Huge carpenter ants came on in the fall. Cedar bugs were an ongoing ever-present horror. My grandfather dubbed them “super friendlies” for their habit of flying right into your face and settling in your hair.

The disjunction between reality and fantasy is captured most notably in an essay from Diana Saverin entitled "The Terror and the Tedium of Living like Thoreau."

Saverin writes: “So I rented a small cabin on a hill, where I was planning to live some version of the American dream, following a template laid out by Thoreau. He’d gone to the woods, as he put it, to live deliberately: ‘to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.’ He’d gone there to ‘suck out all the marrow of life.’ That’s what solitude in the wilderness was all about: living life close to the bone, where it’s sweetest. In my own cabin, I imagined, I’d think in sentences, notice the breeze, leave behind the frivolities of society and technology — everything that wasn’t life raw and vivid and real.”

Saverin’s work is only one ripe offering in the overstuffed collection of essays and images that accompanies the show. With only a short while to buzz through the catalogue, I was staggered by the amount of information it contained.

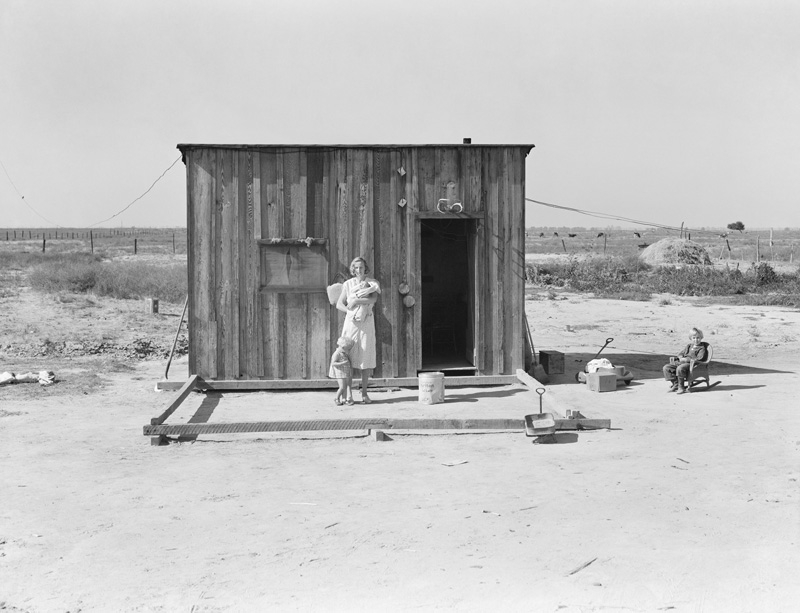

Cabin Fever limits itself to Canada and the U.S., but even within those continental parameters there is an overflowing wealth of material including photographs from Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange and Mattie Gunterman, architectural models, plans, and images from PARTISANS, Patkau Architects, MacKay-Lyons Sweetapple Architects, Eero Saarinen, Rudolph Schindler, Scott & Scott Architects, and paintings from Frederick Varley and Jack Shadbolt. At the centre of the exhibit are 17 architectural models that pull from a variety of different cultural influences from Norway to Scotland. Organized chronologically, the timeline skips along from the modernist era of ski chalets and modular fireplaces to the contemporary phenomenon of tiny houses. Designs from Whistler’s nouveau A-frame to a structure called Grotto Sauna may cause you to covet thy neighbour’s cabin.

Some structures are distinctly humble, ramshackle even, while others are so artfully designed that you could keel over in an architecturally induced swoon. A photographic series of ice-fishing cabins is equal parts twisted and twee. But in the midst of this rich cache of imagery, the final project from Frank Lloyd Wright leaps out. It is a cabin so sublimely elegant and beautiful that viewers might simply combust on the spot. There will be little piles of grey dust where people once stood.

Partly, this variety of form is manifestation of the people building and living in these places. The siren call of the cabin has drawn successive waves of folk into the woods to fashion a home for themselves — from the utopian idealists of Drop City to good old Bucky Fuller’s geodesic domes. In the Kootenays, there were draft dodgers, back-to-the-landers, hippy dippy ideologues and dope growers, right next door to Depression-era farmers who had set up homesteads years before. Some people came, got eaten alive by mosquitoes and promptly returned to the city, but a few stayed and became part of the cultural landscape along with the houses they made for themselves.

Some worked better than others.

In the mid-‘70s, my grandfather came back from delivering a load of firewood to some new arrivals who had decided to build a geodesic dome on top of a mountain. “Those people are going to die up there,” my grandfather said matter-of-factly. A prediction that proved almost true as winter descended and the dome was impossible to heat.

Other structures, like Leaf House on Hornby Island, are so well integrated into the landscape that they look like they simply sprouted overnight, a kind of mycelium structure.

Cabin Fever is replete with different ideas (Utopia! Distopia! Porn!), as well as astounding objects. A model of Fuller’s famous dome is in place, as is a full-size edition of Liz Magor’s cabin. I wandered around, bumping into the army of gallery workers who were busily assembling the show in time for opening day on June 9, but there was simply too much to process. This is an exhibition that requires more than a couple of visits.

More critically, there is much to think about and a desire to return to cabins of yore, seminal cabins, if you will, not just Thoreau’s joint, but also Little House on the Prairie. It’s tricky to untangle your own personal associations, dreams and fantasies from the images on display, but perhaps that is the point of Cabin Fever.

Moving from the fundaments of shelter and survival to a luxurious jewel box on a hill speaks to the wider cultural shift. But something core remains. The impulse to strip away all excess and get right down to the bare blunt parts of existence emerges most clearly in the show’s catalogue. (After all, writers and cabins go together like cheese and wine.) Artists such as Edward Abbey, Margaret Atwood, James Benning, W.E.B. DuBois, Karl Ove Knausgaard, Michael Pollan and Henry David Thoreau each grapple with what the cabin means.

As curator Volland writes in her essay, her attraction to the idea originated from the “combination of humble shelter and sublime landscape.”

The call of the cabin endures, offering up the possibility of another kind of life, one where we are an integral part of the place we live. Whether that is nestled into a hillside o’er-looking a lake or curled deep in the forest, we are home.

Secrets & Lies

On Sept. 28, 2016, some 14 counts of fraud were levelled against a notary public named Rashida Samji.

Over the course of 10 years, Samji had convinced almost 300 people to part with more than $110 million, money that was supposed to be invested in winery projects being undertaken in South Africa and South America. Samji’s Ponzi scheme came to a staggering halt when the full scope of the scam came to light in 2012.

But despite being caught red-handed, and ordered to repay the money to the people that she defrauded, the woman never spent a day in jail. All that changed when Samji lost her appeal to the Supreme Court of Canada this past week.

All of which is rather curious timing for a new production from Theatre Conspiracy. Director Jiv Parasram brings the complex story to life with the help of artistic director Tim Carlson and Playwright Theatre Centre’s Kathleen Flaherty. Victim Impact opens on June 8 at the Vancouver East Cultural Centre.

Parasram recently answered a few questions for The Tyee about the production.

Although, she hasn’t served any jail time, Samji’s life is relatively normal. She has a job and is still out there walking around, but as Parasram points out her life isn’t quite what it once was when she lived high on other people’s money.

As Parasram relates even after the script was assembled, the tone often changed as evidence continued to roll in. In the face of ongoing developments, fashioning a narrative was something of a challenge. In addition to the amount of information available about the case, the proceedings needed to be clarified as much as possible while retaining a sense of the larger picture. But ultimately it was the emotional impact that arose from a profound sense of betrayal that fuelled the production.

Although white collar crime isn’t as exciting as a bank heist, the inherent drama of the grift is replete in the story. There was also a cultural aspect with many members of the South Asian community targeted and predated upon by Samji and her accomplice Arvin Patel, who worked at Coast Capital Savings. Many of the connections came through personal contacts and even the credit union itself when its façade of trust and good faith was exploited.

Ponzi schemes are confidence games, and the taken often feel culpable. Despite the lack of violent criminal acts, there is still a sense of assault and trespass. In the case of Samj’s crimes, the nature of her betrayal took place on a community level. As Jiv points out, “Microfinance is really important to migrant populations, it helps a community to grow.” He goes on to explain the hybrid nature of the play that involves a podcast encompassing more detailed information about the case. The added context allows audiences to come to the show with a more thorough grounding in the story. “It’s really handy,” Parasram says, “to talk about the larger picture of fraud.”

But what does he want people to take away with them? “A sense of caution,” he says. Be careful where you place your trust, pay attention and be vigilant.

All sound advice in a precarious world. And another reason to flee to the forest and build a cabin far away from predatory humanity.

Fashion is a cruel mistress

If you need a little frivolity, some capes and a gigantic outsize sense of style, then The Gospel According to André is just the ticket. Kate Novack’s documentary portrait of André Leon Talley is filled with its titular subject’s irrepressible energy and character. At the centre of the fashion world since he moved to New York at the height of the ‘70s disco debauchery, the man worked at Interview Magazine and Vogue and was Diana Vreeland’s trusted accomplice. Even for those who think fashion is slightly insane, this is a fascinating film about the changing world of style, as well as a powerful reminder of the ongoing forces of race and class that continue to dominate American culture.

And with that, I am off to Paris, to see what André Leon Talley calls the place of “true originality.”

Au revoir, Angler! ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: