Canada’s road to net zero by 2050 will be bumpy, winding and “daunting.”

That’s the mathematical conclusion of David Hughes, one of Canada’s foremost energy analysts, in a comprehensive new report for the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives released today.

Hughes, a geoscientist and resident of Cortes Island, looked at what changes are needed in the nation’s energy mix to meet that goal. He found that the scale of change is mind-boggling. Moreover, the transition to net zero by 2050 hasn’t really begun yet.

According to recent projections by the Canada Energy Regulator, or CER, industry will have to:

- scale up wind and solar production by more than 10 times;

- increase controversial carbon capture and storage by 34 to 39 times;

- beef up direct air capture (a nascent technology) by 4,600 to 5,500 times its current world capacity;

- increase hydrogen production to 12 per cent of energy supply from nearly nothing;

- nearly triple nuclear power;

- reduce per capita energy consumption by up to 40 per cent;

- decrease fossil fuel production by up to 70 per cent; and

- triple the ability of Canadian forests to sequester carbon.

Under one of the Canada Energy Regulator’s successful scenarios, the LNG Canada terminal under construction in Kitimat would have to shut down in 2045, 20 years before its designed lifespan, stranding the $48.3-billion cost of the terminal and the Coastal GasLink pipeline built to supply it.

In other words, beyond driving electric cars and erecting windmills, there are many complexities and conundrums in striving to reduce emissions by 2050.

To add to the challenge, by Hughes’ analysis the Canada Energy Regulator projections include a whole bunch of questionable assumptions, and they do not mention real-life obstacles such as crumbling supply chains, populist politics, incompetent elites, technological disruptions, metal shortages for renewables and global inflation.

Future projections also ignore the open resistance by Alberta and Saskatchewan, which are dependent on fossil fuel revenue, to any substantive change in the energy mix.

Hughes said he wrote the report for one reason: “My objective is to provide policymakers and the public with an understanding of the scale of the problem so they can appreciate the scale that any solution is going to have to take. Only with understanding and buy-in can the necessary changes be implemented.”

He also wanted to put the math all in one place for people for easy reference.

Hughes told The Tyee that a key part of any viable solution will be the seldom heard and little discussed policy of radical energy conservation.

“Maximizing reduction of energy demand through conservation, efficiency and behavioural change will reduce the need for costly energy production infrastructure, as well as infrastructure to capture emissions, and should be at the forefront of government policy incentives.”

Energy consumption today, assumptions for tomorrow

Hughes’ analysis begins with an overview of how our global love affair with fossil fuels powered an emissions crisis over the past two centuries. He then looks at energy production, emissions and energy sector revenue within individual provinces and the country as a whole.

Then he analyzes the net-zero scenarios offered by the Canada Energy Regulator last year, which are based on an economic analysis of current and declared government policies and the most comprehensive knowledge base of Canadian energy data available.

Finally, Hughes reality-checks the CER’s assumptions, some of which are extremely optimistic, to develop an understanding of what a transition to net-zero emissions might require.

The Canada Energy Regulator offered three possible pathways to net zero in its report "Canada’s Energy Future 2023." In one scenario, Canada and the world actually accomplish the goal; in another, Canada achieves net zero but the world doesn’t; and in a third scenario, Canada sticks with existing policies and reduces emissions only 16 per cent from 2022 levels by 2050, guaranteeing accelerating climate disorder.

The only major difference between the world and Canadian scenarios is fossil fuel consumption. If the global system hits net zero by 2050, fossil fuel production declines more rapidly and LNG will be stranded in Canada; if only Canada achieves that goal, then fossil fuel production will continue at a higher level along with some LNG exports.

Hughes calls the "Canada's Energy Future 2023" report “an important first step in evaluating what it will take to meet Canada’s net-zero mandate.”

But before delving into his cold reality check on achieving net zero, Hughes takes a hard look at our current energy predicament.

Governments and citizens rarely appreciate, let alone grasp, their dependence on fossil fuels.

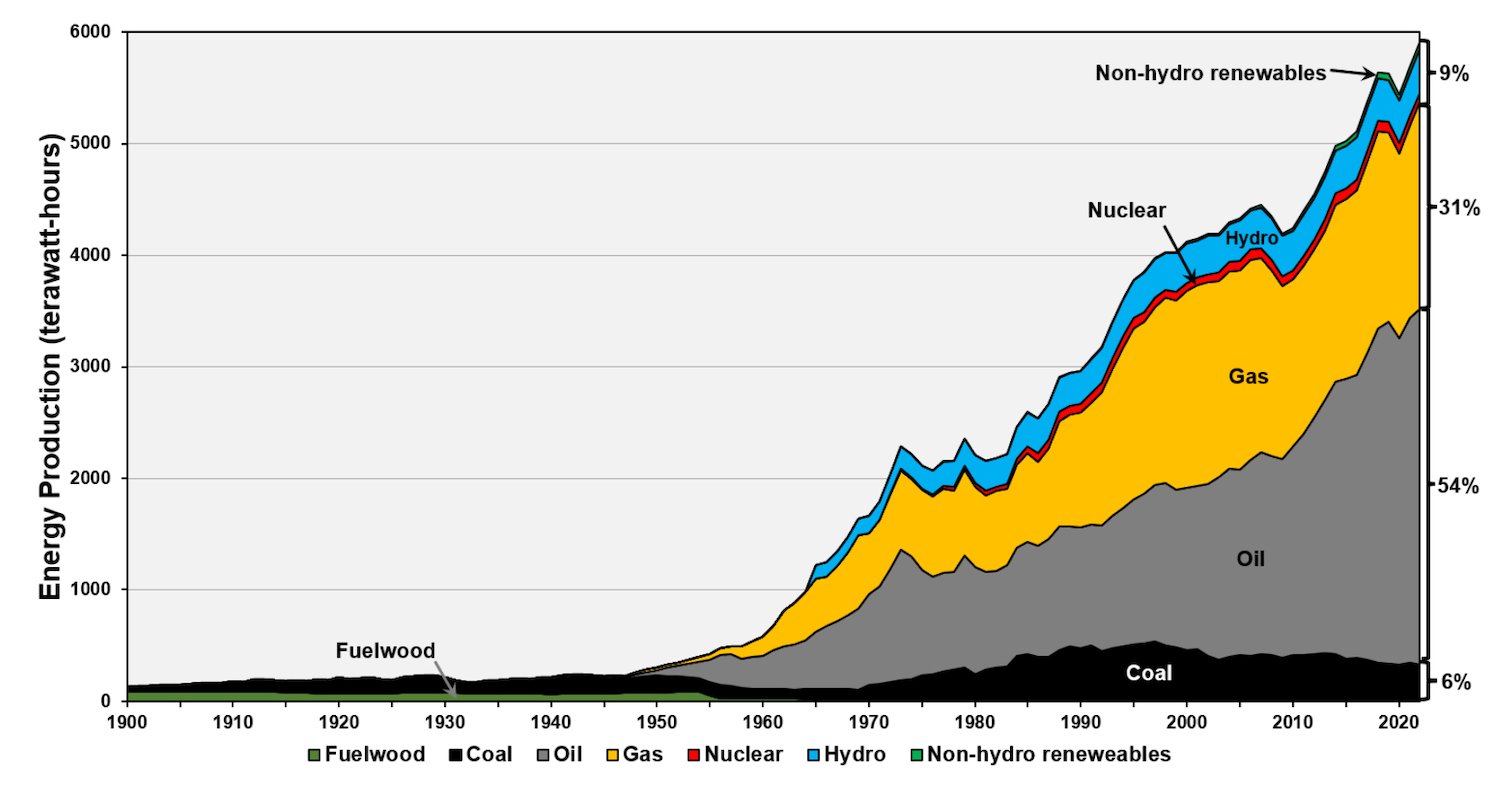

Fossil fuel consumption drives economic and human population growth. As Hughes notes, half of the oil consumed by humans has been burned in the past 27 years; half of the gas in the past 21 years; and half of the coal in the past 37 years. Since 1800, annual energy consumption has increased 32 times.

Meanwhile population has increased eight times and gross domestic product or GDP has increased 114 times. Clouds of carbon emissions have increased 1,321 times.

As a result, half of the world’s 1.77 trillion tonnes of energy-related carbon dioxide emissions have been released in the past 30 years. Fourteen per cent have been emitted since the landmark Paris Agreement of 2015. Per capita energy consumption has also increased 3.9 times since 1800 due to the rapid growth in consumption of fossil fuels.

To date, renewables haven’t made much of a dent in energy consumption or per capita fossil fuel use, notes Hughes. Renewables have “only served to increase overall energy consumption.” In 2022 fossil fuels still accounted for 82.9 per cent of total world energy consumption.

Canada reflects fossil fuel’s dominance of energy flows and then some. For starters Canada has one of the highest per capita energy consumption rates in the world. Canadians spend energy at 4.9 times the world average and 2.8 times the European average. As profligate spenders, Canadians are profligate emission producers.

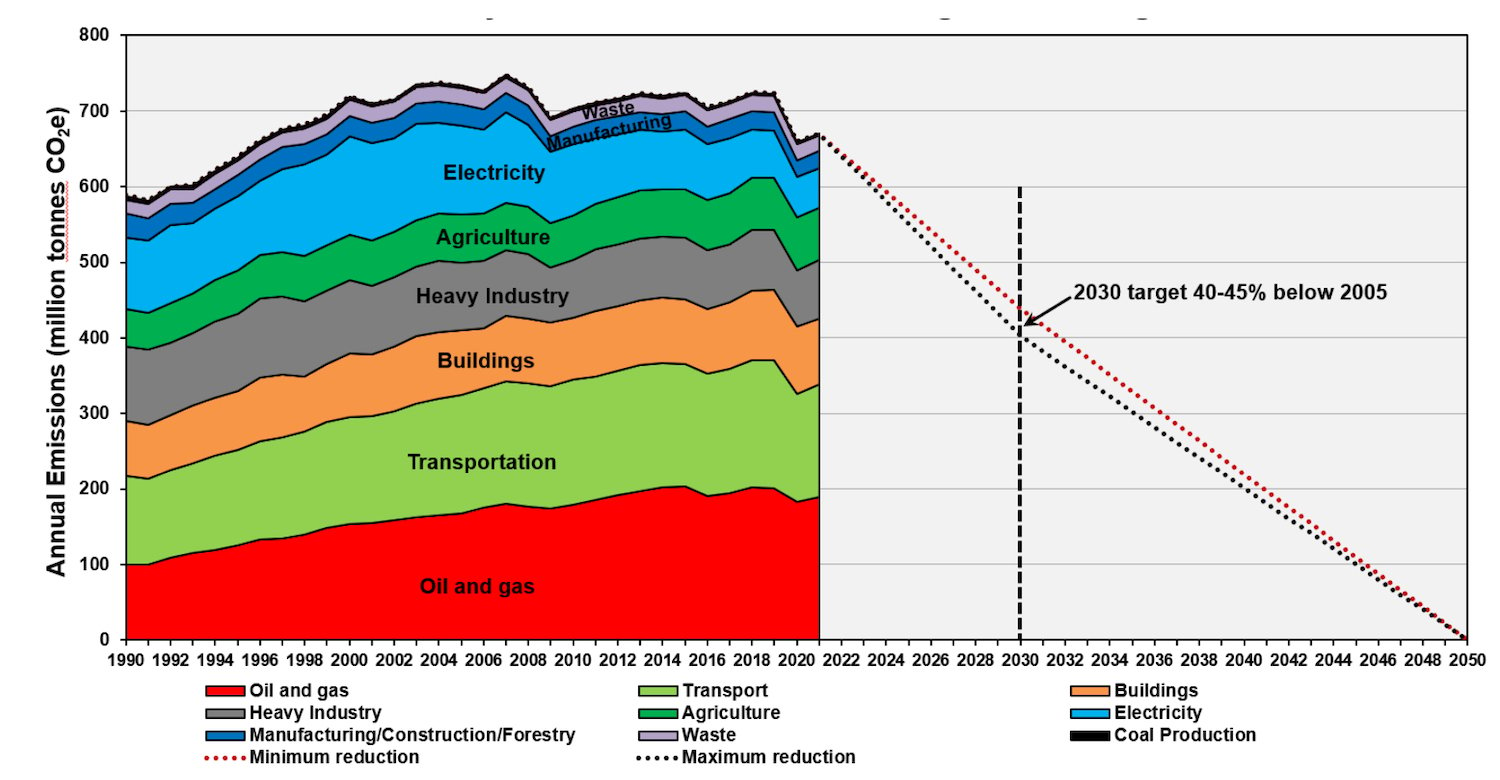

Canada is also the world’s fourth-largest oil producer. More than half of the country’s production is exported. Not surprisingly oil and gas extraction accounts for the single largest source of the country’s greenhouse gas emissions: 28 per cent. Since 1990 oil and gas emissions have grown to 189 from 100 megatonnes per year due to rising production and exports. Meanwhile the petro-economies of Alberta and Saskatchewan produce 48 per cent of Canada’s emissions yet have only 15 per cent of the country’s population.

Hughes notes another issue. Given that it takes energy to grow the economy, significant drops in emissions over the past two decades have occurred only during the 2008-09 recession and the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Canada faces daunting challenges in meeting its net-zero commitments,” Hughes writes. “These are not insurmountable but must be clearly understood and faced head-on with policies and incentives commensurate with the scale of the problem.”

Identifying the ‘big ifs’

As things now stand, Canada gets 90.8 per cent of its primary energy production from fossil fuels (54 per cent from oil, 31 per cent from natural gas, six per cent from coal). The remainder comes from hydro, nuclear and renewables. These percentages must change places to get to net zero.

The CER’s two successful scenarios assume that this is possible but with what Hughes considers a lot of questionable big ifs.

The first big if Hughes analyzes concerns the near tripling of nuclear capacity with small modular reactors. Canada would need more than 80 of these reactors built by 2050 even though only one is currently under construction. Hughes doubts that is a realistic goal unless costs and construction times can be significantly lowered. That’s something that doesn’t seem to happen in the real world anymore, particularly with nuclear power.

The next big if concerns controversial carbon capture and underground storage, or CCS — the building of facilities to capture and bury carbon under the ground for thousands of years. Even the International Energy Agency admits “the history of CCS has largely been one of unmet expectations. Progress has been slow and deployment relatively flat for years. The current level of annual CO2 capture of 45 megatons represents only 0.1 per cent of total annual energy sector emissions.”

According to the CER’s net-zero scenarios, industry would have to add 1.5 to 1.8 times Canada’s total current CCS capacity every year from now until 2050. Hughes doesn’t think that’s desirable or realistic.

Why not reduce dependence on fossil fuel even more instead? he asks.

Direct air capture raises similar problems. The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists recently called the infant technology dangerous and stupid.

“Unlike other climate technologies, the only way to make air capture a business is with oil production and perpetual giant subsidies. Misallocating resources to air capture makes the planet hotter. The only winners are the recipients of the subsidies and the builders of the boondoggles,” say the authors.

The next big if concerns the overall issue of cost. The Canada Energy Regulator largely assumes in its successful scenarios that the cost of renewables, hydrogen, batteries, CCS and nuclear power will magically go down. Yet even the International Energy Agency notes that is not the current reality: “Costs have started to increase rather than decrease in the last two years for some clean technologies such as solar photovoltaic and batteries, reflecting inflationary pressure and, in particular, surging costs for critical minerals.”

Next comes the issue of overhyped hydrogen. The Canada Energy Regulator assumes it will play a big role in getting to net zero. Hughes questions that assumption: “The use of hydrogen as an energy storage medium is in its infancy and its current production for the chemical industry is very energy- and emissions-intensive,” notes Hughes. Furthermore, “producing hydrogen from renewable electricity costs 54-82 per cent of the energy in the electricity used.” Although some hydrogen will be needed for hard-to-electrify uses, reducing the amount in the CER’s scenarios by half would be more realistic.

What it will really take

Hughes concludes that getting to net zero will be a steep, hard climb and will take much more aggressive policies than those currently on display in government.

Rather than assume that carbon capture and underground storage or direct air capture can be affordably scaled tens of times from current levels before 2050, Hughes recommends reducing fossil fuel demand by half compared with the CER scenarios.

He adds that reducing fossil fuel demand will require scaling up the proportion of energy demand supplied by electricity, which will mean more renewable generation. (Remember: hydro and renewables made up only 11.8 per cent of end-use energy demand in 2022.)

Canadian forests cannot triple their ability to sequester carbon (as the Canada Energy Regulator’s scenarios envision) without major changes in industrial practices. As Hughes reports, they have become major carbon emitters, not sinks.

The carbon released from last year’s wildfires exceeded the country’s total GHG emissions. “Clearcuts replaced with combustible monocrops” have compromised the ability of forests to capture carbon from the air, reports Hughes.

Lastly, Canadians will have to use much less energy to prevent an acceleration of the climate crisis. And that means an end to economic growth.

“Mother Nature has other priorities,” Hughes told the Tyee. “We are going to have to accept contraction, unfortunately. It has been a slice. But the math does not work for continuous growth.”

Echoes from US experts

Hughes’ findings are mirrored by a U.S. study published by the academic journal Sustainability. The authors conclude that, yes, it is theoretically possible to achieve net zero by 2050 with the following conditions.

Energy demand must be constrained to 25 per cent or less above the present level.

The development of renewable energy sources must be done at six to eight times the present rate.

Governments would have to apply aggressive energy efficiency and conservation measures; nuclear power would expand by 30 per cent or more.

Per capita energy use would need to fall by 40 per cent or more.

And carbon capture, utilization and storage technologies would have to be built everywhere.

“We readily acknowledge achieving these goals in practice will depend on some technological breakthroughs and a high level of international co-operation that are both uncertain and may not be possible,” say the U.S. researchers.

They also admit that the availability of land and metals may make the achievement daunting.

The researchers also note, as does Hughes, that “added renewable energy is not yet replacing fossil fuels because of growth in energy demand due to increases in population and per capita consumption. It only met 42 per cent of increased energy demand in 2019.”

The researchers say the biggest uncertainties in their scenario “are whether renewable energy can be increased sixfold and whether demand increase over the 2020 level can be constrained to 25 per cent.” ![]()

Read more: Energy, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: