The so-called “zombie deer disease” has arrived in British Columbia.

Experts who’ve long predicted the day would come without firm government action say that chronic wasting disease threatens deer and other public wildlife in the province. And they warn chronic wasting disease could put at risk agricultural trade, food sources for First Nations and licensed hunters, and even human health.

The B.C. government quietly announced on Feb. 1 that it had detected chronic wasting disease in a mule deer shot by a hunter and in a white-tailed deer killed by an automobile from the Kootenay region south of Cranbrook.

The Canadian Food Inspection Agency reference laboratory confirmed the diagnosis on Jan. 31, 2024.

Chronic wasting disease is a relative of bovine spongiform encephalopathy, commonly known as mad cow disease, which caused extensive global trade disruption. It’s been described as the pathogen from hell, or what scientists call “a new challenge for wildlife epidemiology.”

It is already responsible for a population decline in mule deer in North America, reversing decades of conservation work.

Some experts fear it may become an extinction event for deer: infected populations in some parts of the continent are already experiencing mortality declines of 10 to 20 per cent a year.

“What does the extinction of deer mean to an ecosystem and the food security of the First Nations?” asked Darrel Rowledge, director of the Calgary-based Alliance for Public Wildlife. “People in B.C. need to start asking questions about cause and consequence of this disease.”

Rowledge, a hunter and businessman, has been talking about and tracking the spread of the brain-eating disease for nearly 30 years and advocating for government action with limited success.

“I wasn’t surprised by the B.C. news. The border won’t stop this disease,” Rowledge told the Tyee.

“This is a highly fatal and contagious disease that humans created. Absent a miracle, it's an extinction event for deer. It presents devastating threats for trade and our economy, and the possible implications for human health are all but unthinkable.”

The B.C. CWD surveillance and response plan issued a similar dire warning in 2023: “The diagnosis of CWD in one or multiple cervid populations in B.C. has the potential for far-reaching conservation, social and economic impacts. The disease threatens food security for First Nations and licensed hunters, cultural traditions, agricultural practices and local economies.”

How chronic wasting disease kills cervids

Chronic wasting disease is caused by a prion, a misfolded protein, that destroys brain cells in mule deer, moose, elk, sika deer and reindeer. The brain-eating disease is 100 per cent fatal and highly transmissible, especially among captive populations of deer raised in confined feeding operations. It has an incubation period of 18 to 24 months.

As soon as a deer is infected, it begins to shed infectious prions in semen, blood, urine, saliva and antler velvet to other deer and its surrounding habitat. Before death, an infected deer will drool, lose coordination, waste away and behave in a demented fashion.

The 230 people killed by mad cow disease in the United Kingdom all died in a similar and horrible fashion. That event in the 1990s occurred after the contamination of U.K.’s beef food chain by 180,000 contaminated cattle that had been fed bone meal.

Brain-eating prions simply defy traditional biology. They are smaller than the smallest known virus and can survive in tissue long after death. They can cross the species barrier and incubate for decades. They appear to be almost indestructible and can contaminate pastures, animal feed, feeding equipment, medical tools and blood. Only combustion at 1,000 degrees Celsius can destroy prion infectivity. Incredibly, prions can remain infectious after burning at 600 degrees Celsius.

According to Rowledge, decomposing carcasses flood prions into the environment, “binding to minerals and creating ‘super-sites’ that remain infectious for years or even decades.” In addition to direct animal-to-animal spread, CWD prions remain infectious on plants and almost any surface, in soil and water, and can persist in the environment for decades.

Chronic Wasting Disease is now the largest biomass of infectious prions in global history and many experts are concerned that a spillover into humans could cause a nightmarish pandemic. Following the experimental transfer of the chronic wasting disease to macaques, the closest non-human primates allowed in research, Health Canada concluded in 2017 that “CWD has the potential to infect humans.”

The World Health Organization also advises that no meat that is likely to carry the agent for chronic wasting disease should enter the human or animal food chain.

Yet Rowledge estimates that as many as 25,000 hunters are eating contaminated venison every year on the continent. “If people are shown susceptible, it will be chaos, with massive campaigns to slaughter the deer spreading indestructible prions into our food supplies. The world would stop our agricultural exports; it would shut down our economies, and we have no conceivable solutions,” said Rowledge.

Some jurisdictions test for chronic wasting disease in killed deer but others do not. The testing also takes weeks to complete.

The origins and spread of chronic wasting disease

Chronic wasting disease first erupted at an experimental agricultural station in Colorado in 1967 where scientists were conducting feeding experiments on captive deer. Sheep infected with scrapie, another prion disease, served as the control group.

Originally confined to Colorado, the new disease soon spread thanks to the legalization of the game ranching industry in the 1980s. That controversial industry rears captive elk or deer in pens for meat, antlers or sport shooting.

Promoted by politicians such as Alberta premiers Don Getty and Ralph Klein to supposedly diversify agriculture, the captive wildlife industry spread chronic wasting disease and other diseases such as tuberculosis from the U.S. to parts of Alberta and Saskatchewan where wild and escaped captive deer mingled.

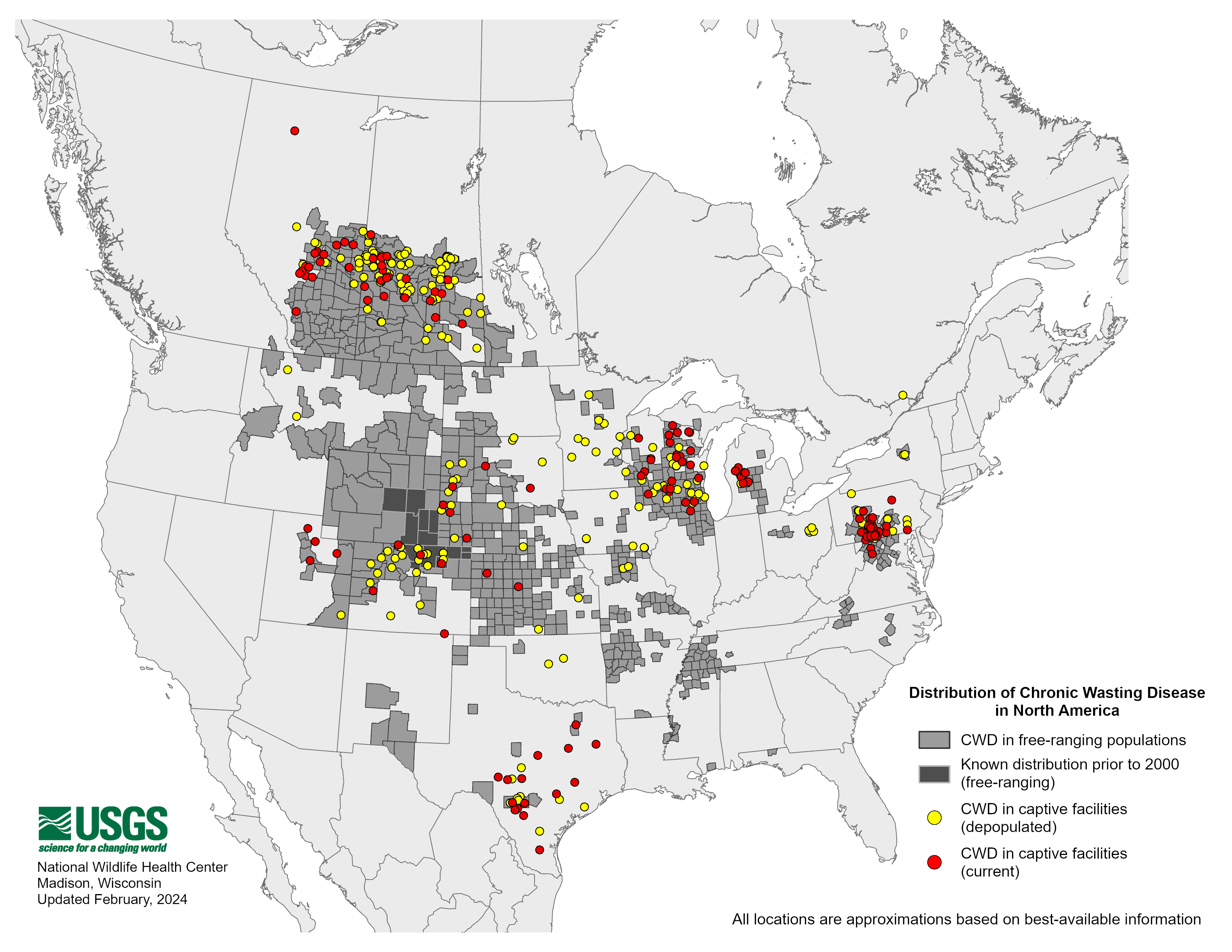

Since then, the movement of carcasses and even contaminated hay has spread the almost indestructible pathogen across the continent and to other species such as moose. Zombie deer disease can now be found in 32 states, five Canadian provinces, Norway, Finland, Sweden and South Korea.

The threat of agricultural trade sanctions are real. Due to a serious chronic wasting disease outbreak among reindeer, Norway banned imports of hay or straw from any state or province with chronic wasting disease in 2018.

“We have been watching CWD spread province to province, state to state for at least 20 years, so this is terrible news for British Columbians,” said Jesse Zeman, Executive Director of the B.C. Wildlife Federation. “CWD is devastating to cervid populations. Continued vigilance and testing are key to organizing preventative measures.”

But Rowledge told the Tyee that governments have been watching the spread of the disease for decades and doing nothing. The fact that there still exist game ranches in Alberta and Saskatchewan actively spreading disease, he added, is scandalous.

“We need to control this epidemic by restricting the movement of captive deer or wild carcasses and we need to make sure contaminated meat is not entering the food chain.”

Rowledge has called upon governments to “enact and enforce an immediate ban on the movement of all live cervids, all potentially CWD-infected carcasses, animal parts, products, exposed equipment, or other sources of infectious materials.”

In addition, government needs to “eliminate cervid farms with a plan for compensation and/or transition of operations to acceptable alternatives.”

Governments must also mandate “convenient, cost-free, rapid testing of all animals harvested from CWD-affected areas.”

Could chronic wasting disease jump to humans?

A growing number of scientists are seriously concerned about chronic wasting disease possibly spreading into human populations.

In fact the University of Minnesota’s Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy, or CIDRAP, recently launched a program enlisting 67 experts from around the world to prepare for a possible spillover from deer to humans or domesticated farm animals.

“There’s no evidence yet that we’ve seen crossover into humans, but what if it were to happen?” epidemiologist Michael Osterholm recently asked in Fortune magazine. “There’s enough concern that it could happen that we have to be prepared. If we find 25 years from now that all this work we did was unnecessary, that would be the greatest victory of all.”

One recent U.S. study found that climate change will accelerate the spread of the disease in south Texas and compromise efforts to manage and control its spread in leading to near extermination of deer in that state. ![]()

Read more: Indigenous, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: