Provincial and municipal officials were warned repeatedly that the dikes in one of the cities hit hardest by the floods that paralyzed southern British Columbia in 2021 were structurally unsound and could fail should water levels in local rivers rise quickly.

For years preceding the disaster, however, they did nothing to fix the City of Merritt’s seriously compromised frontline flood protection infrastructure.

When a pineapple express slammed into southwest B.C. in mid-November that year, the Coldwater River, swollen with rainwater and snowmelt, pushed through the city’s dikes like an ocean wave washing away a sandcastle.

Merritt’s drinking and wastewater treatment plants were then overwhelmed, triggering an emergency evacuation of the city’s 7,000 residents.

The severe flooding caused at least $150 million in property damage, including to scarce rental housing. More than a year-and-a-half later, hundreds of Merritt residents are still not back in homes rendered uninhabitable by the catastrophe.

The failure to respond to one damning report after another is captured in over 5,000 pages of documents released in response to a freedom of information request by the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives B.C. office. The documents also raise questions about lax provincial government oversight of dikes in Abbotsford and Princeton, two other communities where dikes failed.

The FOI request was filed after the extensive flooding that paralyzed southwest B.C. in 2021. The disaster caused sections of highways and bridges to wash away, destroyed or extensively damaged farmlands, farmhouses, residential homes and businesses and triggered a landslide that raced down a mountainside killing five people. The repair bills soared into the billions.

One lonely email

Under British Columbia’s Dike Maintenance Act, local diking authorities must file annual inspection reports with the provincial inspector of dikes. The inspector is then supposed to review those reports and can order local authorities to take corrective action.

The CCPA-BC requested copies of all such inspection reports filed between 2017 and 2021 by the cities of Abbotsford and Merritt and the Town of Princeton — the three communities where sections of dikes collapsed and extensive flooding occurred — as well as reports filed by the cities of Chilliwack and Richmond.

The FOI request also asked for copies of all responses, including any orders from the provincial government.

But in the nearly 5,300 pages of FOI documents, not one order by the provincial inspector of dikes — or any deputy inspector — is found, despite evidence of chronic problems.

In fact, the FOI records furnish only a single provincial government document — a lonely email — from one public servant to another where the substandard nature of Princeton’s dikes is noted, but only after its dikes were overwhelmed by surging rivers and the damage done.

‘Severely compromised’

The FOI record shows that in 2018 both officials in Merritt and the provincial government knew that the city’s dikes were plagued by problems.

A report prepared for Merritt by Aaron Hahn, a registered professional engineer with Interior Dams (an Okanagan-based company), noted that sections of Merritt’s dikes were “severely modified by unauthorized excavation and soil stockpiling” and that fixing those dikes must be a “high priority,” meaning that problems be addressed within two years.

That didn’t happen.

Hahn also noted that sections of the dike had been undercut or scoured by the river and that “reinstating” or “reconstructing” those dike sections was a high priority.

That didn’t happen either.

Hahn further noted there was rampant unchecked growth of large cottonwood trees and other vegetation along sections of the dike, which he warned had “severely compromised the integrity of the dike structure.”

Removing the trees and restoring those dikes must be a high priority, Hahn wrote.

Once again, that didn’t happen.

We know this because in each of the following three years, Hahn was contracted for more work by the City of Merritt and each of his subsequent reports noted the same problems, which the city then sent along to the province.

His last letter and report prior to the flooding were dated June 19, 2021, noting that with the “exception of minor changes to erosion patterns and vegetation growth,” all earlier problems and more remained.

“Unauthorized excavations” had occurred at several places. Private property owners had illegally built fences and stairs on the dikes themselves. “Excessive” tree growth continued to destabilize the dikes. Riprap, or stone used to line riverbanks and prevent erosion, had washed away making the dikes vulnerable should river levels rise.

Lastly, dike walls were slumping and dike crests narrowing, which compromised the flood protection infrastructure.

“Interior Dams recommends immediate implementation of maintenance and other activities,” Hahn wrote to Danyal Malkani, an engineering technologist with the city.

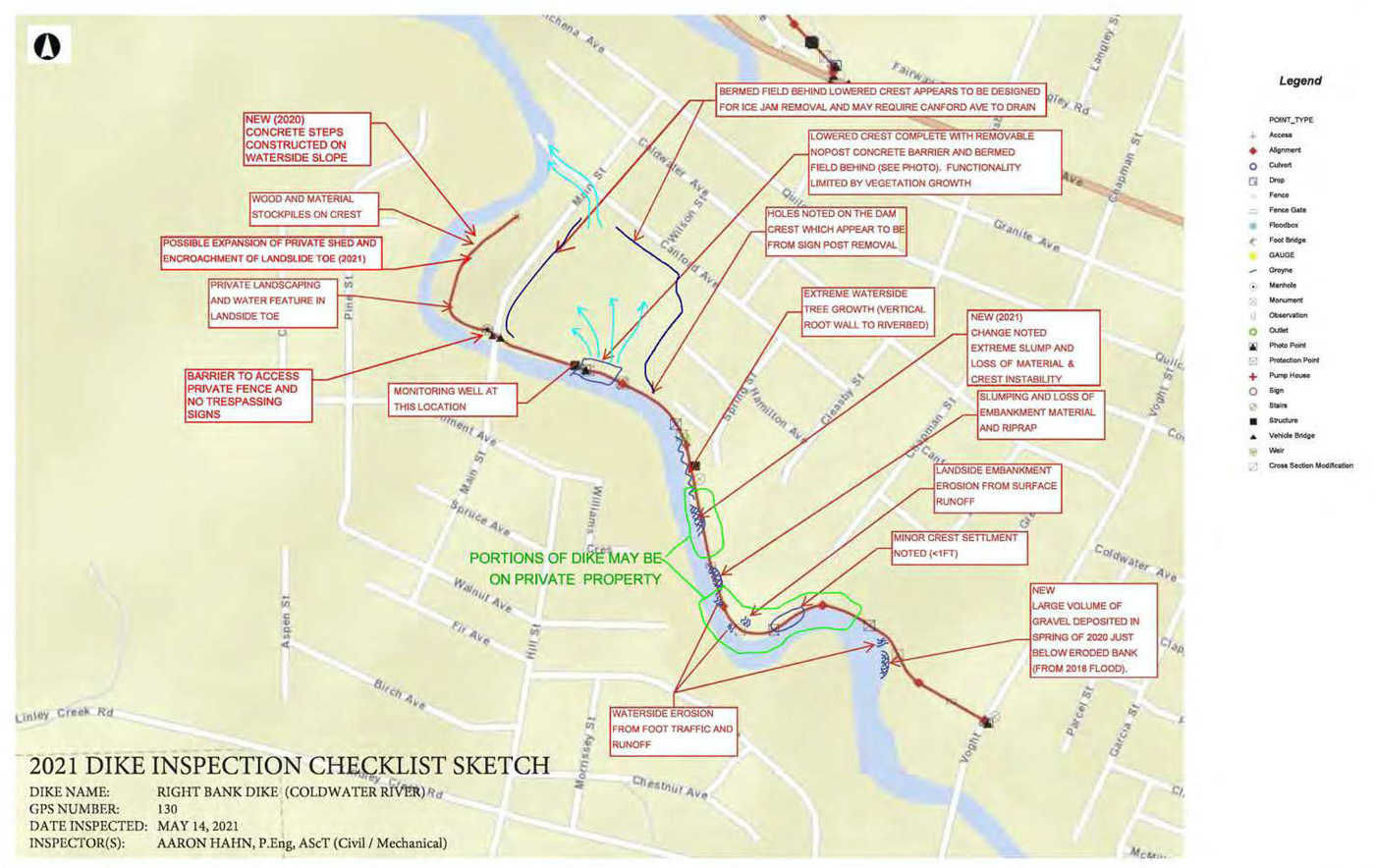

A map prepared by Hahn flagged 19 issues of concern on the left bank of the Coldwater River, including evidence of a sinkhole near the dike, unmapped drainage pipes, “severely eroded” dike sections, “irregular” dike crests and a “large slump.”

A second map itemized 16 additional problems on the river’s right bank including eroded sections of dike due to excessive foot traffic and water runoff and instances of “extreme” slumping and lowering of the dike’s crest height.

Less than five months after Hahn’s report, Merritt’s structurally unsound dikes failed, just as city and provincial officials knew or ought to have known they would.

Cut and paste inspection reports

The City of Merritt was not alone in submitting dike inspection reports to the province that ought to have rung alarm bells.

When heavy rains began falling in mid-November 2021, the Town of Princeton’s dikes proved no match for the overflowing Similkameen and Tulameen rivers.

When the dikes failed, widespread damage occurred to several blocks of houses, including multiple-unit buildings housing elderly residents and people with disabilities.

A year after the flooding, many houses remained unlivable or damaged beyond repair and half the town’s residents were still unable to get drinking water out of their taps.

Details on just how poor Princeton’s dikes were not available from the FOI record. A major reason for this is the town filed only minimal information with the provincial inspector of dikes and in most years filed no information at all.

Princeton’s population is less than half of Merritt’s and its budget is under a third of its more populous rural cousin, which may explain why Princeton opted to have town staff undertake dike inspections rather than hiring a professional engineer. While this is permissible under the regulations, registered professionals are bound by a code of ethics and can be sanctioned for failing to adhere to that code, which requires engineers to “hold paramount the safety, health and welfare of the public.” A municipal employee lacking such accreditation is not bound by such a code and may also lack the expertise or sophistication that a civil engineer would bring to the job.

For example, in 2017 the City of Merritt chose not to hire a professional engineer and had one of its own employees do the dike inspection that year. That employee concluded that the proliferation of large cottonwood trees growing on top of the city’s dikes was “providing good stability” to the structures. Just the opposite conclusion was drawn each subsequent year by Aaron Hahn, the professional engineer hired by the city to inspect its dikes.

In Princeton, the reporting by non-professional staff was scant to say the least.

The five-year FOI record furnishes only two annual inspection reports, one in 2018, the other in early 2021, 10 months before the disastrous flood.

Both reports consisted of brief, hand-written notes on a prepared “dike inspection checklist” that the inspector of dikes required local authorities to complete. Notably, Princeton’s report for 2021 actually used the outdated and shorter 2018 dike inspection checklist.

On the first page of the 2021 report, the year 2021 is in a different font than the rest of the document and appears to have been printed out on a separate piece of paper, then cut out and pasted over the year 2018.

Infrequent as Princeton’s reporting was, the handwritten notes revealed enough for provincial officials to know that the town’s dikes were not in good shape.

Yet neither Princeton’s lack of annual reporting nor the cut-and-paste job triggered any alarm with provincial dike authorities. In fact, the sole provincial government document in the FOI record characterized Princeton’s reporting as “relatively satisfactory.”

“Just FYI, this info may not be for now, but may be needed several days down the road,” Rudy Sung, a senior flood safety engineer in the Ministry of Forests Water Management Branch, wrote to Shaun Reimer, head of the ministry’s public safety and protection office on Nov. 15, 2021, the day when the unprecedented flooding visited upon southern B.C. made headlines across the country.

“In the recent years, Princeton has somewhat consistently been submitting the annual dike inspection report… and the report quality has been somewhat satisfactory,” Sung’s email continued before concluding that the dikes along both rivers were “not built to withstand a 200+ year event.”

This, Sung noted, was exactly the kind of event that unfolded on the Tulameen and Similkameen rivers in November 2021, although it was hard to say exactly how engorged the raging rivers became because the force of the rushing water had actually blown out a water gauge.

High enough?

In addition to Merritt and Princeton, the City of Abbotsford filed reports that should have — but apparently did not — trigger a response from the inspector of dikes.

Provincial and municipal officials have known for years that dikes, including those in the populous Lower Mainland and Fraser Valley regions, are lower in height than they should be, in some cases by a metre or more.

Complicating matters, only in recent years have local dike authorities been required to measure and report dike crests in their annual inspection reports.

The FOI record shows, however, that in Abbotsford, the Fraser Valley community that was hit hard by November’s floods when its dikes failed, such measurements weren’t done, or if they were the data was not provided.

Yet Abbotsford’s failure to respond to such a key question did not result in the inspector of dikes ordering Abbotsford to do the measurements and submit a revised report even though the inspector had the powers needed to compel the city to do that work and was part of a professional association whose code of ethics placed a top priority on public health and safety.

A ‘new approach’ to floodplain management

All of this played out against the backdrop of the provincial government having offloaded its floodplain management responsibilities.

In 2003, with the official Opposition reduced to just two NDP MLAs, the provincial government under then-premier Gordon Campbell’s leadership easily passed new legislation — the Flood Hazard Statutes Amendment Act — transferring powers to approve developments on flood plains from provincial to local authorities.

With the change, communities like Merritt, Princeton and Abbotsford could issue new building permits on floodplains without first seeking or obtaining provincial approval.

The new legislation was one of many sweeping changes that effectively moved the provincial government away from prescribing how things were to be done to relying on outside professionals to make such calls, with the province retaining powers to monitor their actions and ensure compliance with relevant regulations.

So began the era of “professional reliance."

“Local governments are best equipped to make decisions about what should or should not be built in their communities," said Joyce Murray, then-minister of Water, Land and Air Protection. “We believe they are perfectly capable of making these decisions in the best interests of their citizens and our new approach gives them the flexibility to do that.”

In the legislature, Murray’s cabinet colleague and then-Chilliwack MLA John Les was an enthusiastic supporter of the bill. Les had been a real estate agent and mayor of the city, which along with neighbouring Abbotsford was in the midst of a building boom.

The importance of the riding that Les represented, whose population was rapidly growing and that had a significant dike system, was reflected in the press announcement, which featured a validating quote from then-Chilliwack mayor Clint Hames.

“These changes are good news for cities like Chilliwack,” Hames said, adding: “The old system didn’t recognize the flood protection provided by our dike network and it interfered with proper planning and development. These changes will reduce the cost of building and buying a new home on the flood plain by thousands of dollars and will result in more logical and effective city planning.”

What remained unchanged, however, was that the province would continue to require local dike authorities to prepare and submit annual dike inspection reports and the provincial inspector of dikes would retain powers to order local dike authorities to take action.

The changes initiated by the Campbell government, and championed by the real estate agent turned politician, were seen by many as a sop to the development industry and in the ensuing years urban sprawl in Abbotsford, Chilliwack and other Fraser Valley communities exploded, upping the consequences should dikes fail.

If anything, such growth should have prompted increased regulatory oversight by the province.

But since the legislative changes, three successive provincial inspectors of dikes (Neil Peters, Mitchell Hahn and Yannic Brugman) — all professional engineers who are bound by the same code of ethics that engineers working in the private sector are — did not issue any orders to local dike authorities to improve deficient dikes.

Or if they did, the government could not point to one.

Is the regulator regulating?

In an emailed response to questions submitted by the CCPA-BC, Nigel McInnis, a senior public affairs officer with the Ministry of Forests, wrote that when the Dike Maintenance Act first became law in 1953 it was “not intended” that dike inspectors would issue such orders.

How, exactly, the ministry discerned what the intentions of the original drafters of the bill were 70 years ago is unclear.

The email, which McInnis asked to be attributed as “background” from the ministry, went on to say that “DMA orders have been typically used to stop works and activities that would negatively impact the dike, or to enable the Diking Authority to perform their dike related duties when there is land ownership or right-of-way issues.”

It then added: “there have been no DMA Orders issued to diking authorities to make improvements to the dikes under their authority in recent years.”

A review of the DMA shows, however, that its drafters gave the inspector of dikes unambiguous powers to force local authorities to perform work on dikes.

The DMA stipulates that the inspector could “enter on any land and on a dike” to carry out inspections and could at any time “require a diking authority… to replace, renew, alter, add to, improve or remove a dike.”

Inspectors could even order local dike authorities to build entirely new dikes and if they felt local authorities were not doing the work in a timely way they could initiate the work themselves and bill the authorities for the cost.

Yet that appears never to have happened, either under the auspices of the Ministry of Forests or under previous ministries that had responsibility for dikes including the briefly lived Ministry of Sustainable Resource Management and before that the provincial Ministry of Environment.

Cowichan Valley MLA and Green Party Leader Sonia Furstenau said she was dismayed that the FOI record appeared to indicate that successive governments failed to use the regulatory powers at their disposal to force needed dike improvements.

Furstenau noted this is far from an isolated problem. The auditor general, for example, examined compliance and enforcement in the province’s mining sector in a 2016 report and the government’s oversight of dam safety in the province in a report five years later. In both cases, the government was found lacking when it came to exercising the regulatory powers at its disposal.

As with dikes, regulatory oversight of dams in the province falls under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Forests but at one time was vested in the Ministry of Environment.

The auditor general concluded that the Ministry of Forests had not adequately verified or enforced compliance with the province’s dam safety regulations, an observation that Furstenau said has parallels with its record of oversight of dikes.

“This is a public safety issue, with lives and the well-being of communities at risk,” Furstenau said. “We need a government that takes its responsibility to protect the public and the environment seriously.”

Furstenau added that the government must become more proactive because the alternative will be potentially bigger, unforeseen bills down the road and not just for replacing deficient infrastructure.

For example, the provincial government is named in a class action lawsuit in Abbotsford as a result of the flood-related damages there and its alleged failure to provide early and effective warning to local residents and businesses of what was to come.

It also faces other potentially significant legal costs stemming from the landslide that killed five people on Highway 99 during 2021’s storms, a landslide that lawyers acting for surviving family members say was triggered by an improperly decommissioned logging road, for which the province bears ultimate responsibility.

Could further class actions await?

“A government that consistently fails to act proactively to create, maintain and protect critical infrastructure will also consistently pay far higher costs when infrastructure fails,” Furstenau predicts.

Fires, floods and a granddaughter lost

As wildfires have raged across the province for much of this year, it’s understandable that few people may have thought much about the floods of two years ago and what awaits us with a new rainy season.

But those very same fires can worsen the severity of future floods. When wildfires burn intensely in watersheds they can change forest soils, making them wax-like. If a huge amount of rain is then dumped on such lands, more water than normal will course downhill into creeks and rivers because the altered soils can’t absorb water like they used to.

Such fires burned near Merritt prior to 2021’s floods, something that Allan Chapman, a professional hydrologist and former head of B.C.’s River Forecast Centre — the frontline provincial agency tasked with warning the public of imminent flooding — says contributed to the “beyond extreme" water levels in the Coldwater River that year.

Hundreds of Merritt residents lost their homes either temporarily or permanently following the floods, including Michael Goetz, who became Merritt’s mayor nearly one year after the epochal event, which many now believe is a harbinger of climate change.

Goetz, however, lost something far more precious, his granddaughter.

Six-year-old Amber Young died during the emergency evacuation of the city when the car her mother, Goetz’s daughter Jordan Goetz Young, was driving hit black ice and collided with a utility vehicle. Goetz’s other granddaughter, five-year-old Hailey, was also in the car and narrowly escaped having to have her shattered arm amputated.

Months later, Goetz, who had previously served on Merritt’s council, became the city’s new mayor. On entering the race, he said his two top priorities were getting the city’s substandard dikes built to a higher standard and encouraging the province to approve more “prescribed burning” — deliberately set and controlled fires — that can help reduce the severity of future wildfires.

A time for bigger steps

Now well into his first year in office, Mayor Goetz is learning just how tough it is to deal with the damage caused by the floods.

He says the provincial government provided much-needed initial help, including $2.9 million to build dikes around the city’s sewage treatment plant so that it would not again be overrun by floodwaters.

The province also provided money to purchase 31 trailers to temporarily shelter people who lost their homes.

“We’ve got 241 houses that are still standing but nothing inside — no walls or ceilings. They are completely uninhabitable,” Goetz says.

More recently, Bowinn Ma, B.C.’s minister of emergency management and climate readiness, announced the province would pay $9.6 million to replace the Middlesboro bridge, which was left half hanging over the Coldwater River after the floods. She also announced the province would provide another $2.5 million to build new dikes in the immediate vicinity of the bridge, without which the bridge cannot be built, Goetz said.

All this is to the good. But substantially more funds are needed to rebuild the city’s deficient dikes themselves, money that has yet to appear from either the provincial or federal governments. This means that “not one rock has moved” to rebuild Merritt’s vital flood protection infrastructure, Goetz says.

The estimated cost to replace the dikes along the Nicola and Coldwater rivers ranges between $140 and $160 million, while the money that Merritt annually collects in property taxes from local residences and businesses is $9 million, Goetz says.

Complicating matters, the city’s industrial tax base has shrunk in recent years with the closure of sawmills. Money — and a lot of it — will need to come from the federal and provincial governments to build dikes that will withstand future flood events, Goetz adds.

George Abbott, who served in three different cabinet positions while Gordon Campbell was premier, said that Merritt’s dilemma underscores the challenges ahead “around magnitude of costs for effective community protection. And floods, of course, are just one of the symptoms of climate change that we need to address.”

He said the disaster and apparent breakdown in regulation demands “a number of shifts in public policy.”

He believes what is needed is an “ongoing federal-provincial-First Nations-local government partnership” that is focused on “planning, prevention, response and recovery” in relation to the climate change-fuelled double-whammy of fires and floods.

It is unavoidable that mounting an effective response to such events will require significant funding and there must be “a dedicated funding stream, whether in the form of a carbon tax, gas tax or novel community protection tax” to do the job, Abbott said, adding that the “costs for response and recovery will continue to grow unless we take bigger steps on prevention and mitigation.”

Taking charge

That bigger steps are needed, is undeniable.

Nine years before November 2021’s floods, the B.C. government released a report that estimated what it would cost to raise “sea dikes” — dikes that protect communities from rising sea levels and that are critical to the well-being of vast numbers of people in the province’s most populous metropolitan region.

The price tag then was just under $9.5 billion.

“Who’s going to pay for that,” John Clague, a geoscientist at Simon Fraser University, asked. “Municipalities don’t have that kind of money.”

Because that now decade-old report was only focused on sea dikes, no estimate was made of the costs to replace or upgrade dikes near villages, towns and cities in the vast interior region of the province where rising river levels can do immense damage, as witnessed in Abbotsford, Merritt and Princeton in 2021 and in communities like Grand Forks in 2018.

In September 2022, 10 months after 2021’s devastating floods, the Union of BC Municipalities passed a resolution calling on the provincial government to take back responsibility for dikes and to dramatically increase funding for flood preparedness.

Hundreds of local government representatives endorsed the resolution. Similar resolutions had been passed by Union of BC Municipalities members in 2014 and again in 2015.

Since then, the province has promised a new flood strategy. To date, however, it has only released an Intentions Paper, which identifies a number of action items including one to “strengthen dike regulatory programs.”

The document does not propose what a strengthened regulatory regime would look like.

Meanwhile, the most-recent provincial budget hints at the challenges ahead.

Citing 2021’s wildfires, an unprecedented heat dome and devastating floods, the provincial government earmarked $1 billion over three years to support communities as they sought to rebuild after the back-to-back-to-back disasters. Another $750 million was earmarked for contingencies over two years for disaster response and recovery, and another $100 million per year over three years to repair or replace “provincial public-sector infrastructure damaged from climate emergencies.”

It is unclear how much of this combined $2 billion-plus in projected spending for disaster response will involve dike upgrades or replacements, as the word dike is not mentioned once in the main budget document’s 182 pages.

But one thing is clear as far as communities most directly in harm’s way are concerned.

The time has come for the provincial government to assume full control of dikes, to co-ordinate and fund the upgrading and replacement of dikes as needed. Also, the province must ensure that when known problems persist at dikes — as was glaringly the case in Merritt — regulatory inaction is investigated and those dikes are fixed immediately to keep local residents safe. ![]()

Read more: Environment, Urban Planning

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: