All summer long millions of British Columbians and Albertans have lived under a grey shroud of wildfire smoke — the North American West’s new and most deadly form of air pollution. Our celebrated blue skies have become another hostage of climate change.

But what happens when escalating levels of wildfire smoke propelled by hotter and drier climate conditions meet an ever-changing COVID pandemic?

Well, you get what one Harvard researcher calls “a very dangerous combination.”

Or what bureaucrats at the United Nations call “unprecedented” territory.

As a result many of us are now living in anxious and uncertain landscapes where wildfire smoke obscures the sun, reddens the moon, silences all bird song, and insidiously inflames lungs and hearts all summer long.

One non-linear global emergency (climate crisis) has collided with another non-linear global crisis (the pandemic) to make matters worse.

We are now living in an evolving science story that highlights how quickly daily life is being rearranged by air pollution, viruses, particulate matter and the unpredictable complexity of climate change.

Marshall Burke, a Stanford expert on wildfire smoke, described the intensity and duration of dirty air in the western United States as a “first order concern.”

He added that "It is going to be the most important impact of climate change felt by millions of Americans and Canadians.”

Smoke will be the rude face of climate change that most people encounter — at least here in the continental West. “It will be on par with heat waves,” said Burke.

Sarah Henderson, a senior scientist at the BC Centre For Disease Control, signalled the threat last summer in the American Journal of Public Health, writing that the pandemic was about to collide with the North American West’s extended wildfire season thanks to hotter temperatures.

She explained that wildfire smoke, a complex body of chemicals, was characterized by high levels of microscopic concentrations of particulate matter that can float around for weeks or months in the air.

Particulate matter, whether created by diesel trucks or burning trees, is a big public health problem.

These ash-like particles, about one thirtieth the width of a human hair, can inflame the lungs and kick the immune system to go into overdrive. It attacks these particles as though they were invading viruses or bacteria. Wildfire smoke poses higher risks to people with heart or lung ailments, the elderly, children and fetuses.

A damaged lung functions as poorly as disturbed soil; weeds and viruses thrive in wounded terrains.

Populations that have inhaled large levels of wildfire particulate tend to have higher rates of hospitalization for breathing and heart problems.

Smoke travels far. A conflagration in Quebec can dramatically affect hospitalization rates in New England, a thousand miles away.

And smoke has been shown to increase everyone’s susceptibility to viral infections, including influenza.

As a result Henderson warned that wildfires could fill the air with clouds of particulate matter and amplify the pandemic.

She estimated that just a moderate season of wildfires, driven by climate change, had “the potential to increase the impact of the COVID-19 outbreak by approximately 10 per cent.”

Turns out Henderson pretty much called it.

Just last week a group of Harvard researchers released a study that actually tested Henderson’s hypothesis, one shared and pursued by other researchers.

The team at Harvard pored over COVID statistics, wildfire data and particulate levels for 92 counties in Oregon, California and Washington during last year’s fire season. Incredibly, the period lasted from March to December.

Then the researchers built a statistical model to quantify “the extent to which wildfire smoke may have contributed to excess COVID-19 cases and deaths in the three states.” (More than 73,000 people died of COVID in the region during the study period.)

Here’s what they found. Wherever particulate matter on average rose by 10 micrograms per cubic metre each day over a 28 day period — the rate much of B.C. and Alberta have recently experienced — COVID cases increased by an average of 11 per cent and deaths by nearly nine per cent.

There was much variation among the areas as one might expect. In some of the smokiest places air pollution played an ever-greater role accounting for more than half of all COVID infections and 70 per cent of deaths.

Particulate matter is measured in micrograms per cubic metre of air. In the Harvard study westerners normally breathed 6.4 micrograms per cubic metre on clear blue days without fire.

But during wildfire season that picture rapidly darkened. Particulate levels rose on average to 31.2 micrograms per cubic metre. In some communities people breathed 500 micrograms per cubic metre of smoke particulate for four days in a row.

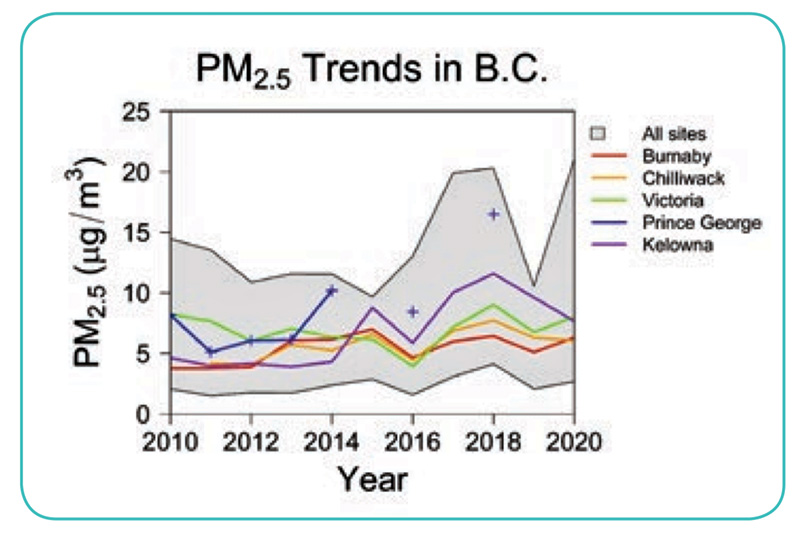

The same story occurred in B.C. Throughout much of this summer many communities in the province’s interior have been breathing 100 micrograms for successive days.

The B.C. government sets a daily objective of 25 micrograms, but thanks to wildfire smoke most interior communities have exceeded that guideline. Such overshoots are increasingly common. During B.C.’s 2017 fire season, for example, particulate levels exceeded the 25 micrograms per cubic metre standard on 33 of the 72 days in Kamloops. On some days, people were breathing 274 micrograms per cubic metre.

The Harvard researchers concluded by saying they had found “strong evidence that wildfires amplified the effect of short-term exposure to PM2.5 on COVID-19 cases and deaths.”

The mechanism, however, is not clearly understood. The researchers suggested that short-term exposure to smoke might do one of two things. It may increase the likelihood of severe infection by turning asymptomatic cases into full-blown disease. Or it may cause more severe infection, leading to death.

There is also a possibility that the virus travels farther in air with higher particulates. And smoke drives people indoors, where the virus is more easily shared.

(Christopher Carlsen, director of the Air Pollution Exposure Lab at UBC, noted that the Harvard study was “correlative but does not link the wildfires to COVID with causative certainty" because there are so many other variables to consider such as masking and existing health conditions. But he added “there is strong biological plausibility for fires worsening COVID” because of the known damage PM2.5 can do to lungs.)

Researchers have long known that air pollution can transform the potency of respiratory viruses. Italian researchers first noticed this COVID connection, as industrial cities like Milan and Bergamo were hard hit by the pandemic last year. Researchers suspect that high levels of particulate matter for two months prior to the pandemic partly explain why COVID hit those places hard.

In the Italian cities, particulate pollution came from industry, not wildfires. But the lesson to researchers is plain. “Populations that live in areas at high levels of pollutants are in a chronic inflammatory state, which makes them more susceptible to respiratory and cardiovascular diseases. “

Other studies have estimated that 17 per cent of COVID deaths in North America could be attributed to particulate air pollution. Another study found that just an increase in one microgram per cubic metre of the average concentration of particulate matter could translate to an 11 per cent increase in COVID mortality.

After the publication of the Harvard study, Francesca Dominici, it’s senior author, offered a telling comment: “This study provides policymakers with key information regarding how the effects of one global crisis — climate change — can have cascading effects on concurrent global crises — in this case, the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Burke, an associate professor of earth systems sciences at Stanford University, salutes that assessment. He is part of a team that has been studying the impact of growing wildfire seasons on human health, and the news is not good.

His team also thought about doing a similar study on COVID and smoke but he’s glad the Harvard team actually did one. “I thought the effect sizes (around 10 per cent more COVID) were reasonable.”

“This is yet another reason why we should do everything we can to avoid exposure to wildfire smoke,” added Burke.

That’s much easier said than done on the North American West Coast and surrounding areas. Or for that matter Greece, Algeria, Italy and Siberia where “unprecedented” wildfires have consumed forests the size of countries.

Burke’s work on wildfire smoke has highlighted some distressing public health trends. Ashen skies used to account for about 10 to 20 per cent of the particulate matter or dirty air that North American westerners would encounter in a year.

“But we’ve seen in the last five years a doubling or tripling of smoke-based particulates in the air,” noted Burke. “It is now the majority of pollution in many areas.”

B.C., a province slow to acknowledge the impact of climate change on its secondary plantation forests, has been no exception.

During its “unprecedented” 2017 wildfire season smoke particulate levels soared. According to a 2018 report by the BC Lung Association, places like Williams Lake and Kamloops particulate matter concentrations in July and August averaged 71 and 48 micrograms per cubic metre.

In what seems like a long time ago, authorities once regarded averages of 3.8 and 5.6 micrograms per cubic metre as “normal” in the region. But those blue skies are increasingly rare.

It is probably no accident that the highest level of COVID infections in B.C. are largely confined to areas in the Interior with the highest daily averages of particulate matter. These regions include the Arrow Lakes and Central Okanagan.

What worries Burke and other researchers is that continental westerners really haven’t seen anything yet. Smoke particulate levels are expected to rise as more heat domes and higher temperatures dominate western Canadian and American summers and dry up our forests.

The public health implications are explosive. “Any exposure is bad and the more exposure you get, the worse it is. There is no safe level,” said Burke.

Moreover wildfire particulates behave the same as any other particulate in terms of public health implications. “Some scientists suggest it may even be worse.”

As climate change transforms forests into ash piles, things are changing so fast that researchers still can’t answer a lot of questions about the dangers of wildfire smoke.

“Do you get more extreme health effects at higher particulate levels above 100? We don’t have a good answer to that,” said Burke.

Still, Burke recently calculated that wildfires in California alone increased mortality by 3,000 deaths over the period of a month in 2020 alone.

“These overall effects can be in large part attributable to climate change, which has dramatically increased the likelihood and severity of wildfire,” he noted on an internet post.

So here’s what science and the smoke is now telling us. Wildfire seasons are now breaking all records while particulate smoke is obscuring our present, and will cloud our future as climate change accelerates.

Smoke-filled skies have abruptly become the dominant form of pollution in the North American West. This dirty air is now damaging our lungs and suppressing our immune systems — sometimes a thousand miles away from the fire.

Hepa filters and N95 respirators will soon replace cowboy boots and Stetson hats as symbols of the North American West.

Meanwhile inflamed lungs are more susceptible to viral infections such as COVID and influenza. And whatever other microbial opportunist that might come along next.

Smoke, just like COVID, targets more vulnerable groups of citizens including those with immature or older lungs.

There is still much to learn about the health impact of wildfire smoke on people living in burning landscapes, noted Burke. It’s as if we exist in a thick haze, trying to understand how to piece together the effects of climate change, a mutating coronavirus and connected threats.

“It has all changed so rapidly,” he said, “that the science hasn’t caught up yet.” ![]()

Read more: Coronavirus, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: