For more than a year now, scientists have been keenly arguing the role of heavy liquid droplets versus tinier, lighter aerosol droplets in feeding the pandemic.

It’s basically a debate about the complex physical behaviour of particles that drop to the ground versus those that float and move around like fine dust.

Droplets spewed from a sneeze, laugh or cough tend to be larger than five microns in size. (Five microns is about one-tenth the width of a thin strand of human hair.)

Many researchers argue that these dense droplets, thanks to gravity, fall to ground, about six feet away from the person sending them forth, and that’s how COVID-19 spreads — just like most respiratory diseases. You inhale a droplet or pick one up from surfaces.

But compared to droplets of such size, aerosols behave much differently. As tiny particles, they can float much greater distances than two metres, attach to dust and hover in the air for hours. They can travel on air currents, too. That means any poorly ventilated room could infect a pile of people in short order.

Says WHO?

Last month, a review funded by the World Health Organization dubiously concluded that COVID-19 wasn’t an unqualified airborne concern.

The researchers argued that they just couldn’t find viable virus travelling in the air: “The lack of recoverable viral culture samples of SARS-CoV-2 prevents firm conclusions to be drawn about airborne transmission.”

The WHO-funded study barely mentions that recovering viruses from the air is damned tricky business, because viral vacuum cleaners typically tend to rip and destroy the outer envelope of the virus.

In contrast, a Lancet paper by a group of prominent researchers (including Canadian epidemiologist David Fisman) called WHO’s conclusions nonsense. The authors offered a variety of evidence to support airborne transmission as the central pathway for COVID-19 infection.

This vital scientific debate, which has been raging for months, isn’t trivial.

If, as the WHO argues, the coronavirus is largely spread by large respiratory droplets, then the status quo is working. All you need to do is wipe surfaces, physically distance and don masks within droplet distance of another person.

But if the virus is primarily airborne, as an increasing number of researchers suspect, then the status-quo policies are as full of holes as Swiss cheese.

Battling an airborne virus, in other words, requires more than the status quo. It requires good ventilation, air filtration, avoidance of crowds especially in any indoor environment, and the use of high-quality masks as well as better masks (N95) for frontline workers.

In a pandemic where aerosols do much of the heavy spreading in crowded and essential workplaces, ventilation then becomes a key intervention while wiping surfaces largely gets demoted to public theatre.

The Lancet case for aerosol spread

The Lancet article explains in plain English why COVID-19 is primarily airborne, and this evidence is worth repeating for public health reasons. Or as another group of Korean researchers put it: “Aerosol transmission indoors with insufficient ventilation needs to be appreciated.”

Here are the facts to know supporting the aerosol argument:

1. Trapped air, shared, is a threat. The spread of infections in big-box facilities has been a constant theme of this pandemic. Superspreading events tend to happen in poorly ventilated and packed indoor venues such as long-term care facilities, slaughterhouses, church choir concerts, funerals, cruise ships, prisons and restaurants.

An infamous Seattle choir group composed of 61 people sang their hearts out for two hours. They washed their hands and kept their distance. Yet 33 contracted the virus and two died. In China, one passenger infected eight of 49 people on a tour bus. One sat 4.5 metres away. Infected restaurant diners have spread the virus to people up to 21 feet away. In one Korean call centre nearly half of the 216-member workforce on an entire floor became infected. And so on.

The location of box-like facilities that spread aerosols among a crowded workforce has had dramatic public health consequences. Per capita infection rates for COVID-19 increased by 110 per cent in communities housing large beef-packing facilities for instance. The rate climbed to 160 per cent with pork slaughtering.

2. The virus floats through vents. In Australia, people staying in quarantine hotels in separate rooms have acquired COVID-19 — proving that aerosols can move through ventilation systems that are largely designed to control odours, not viruses.

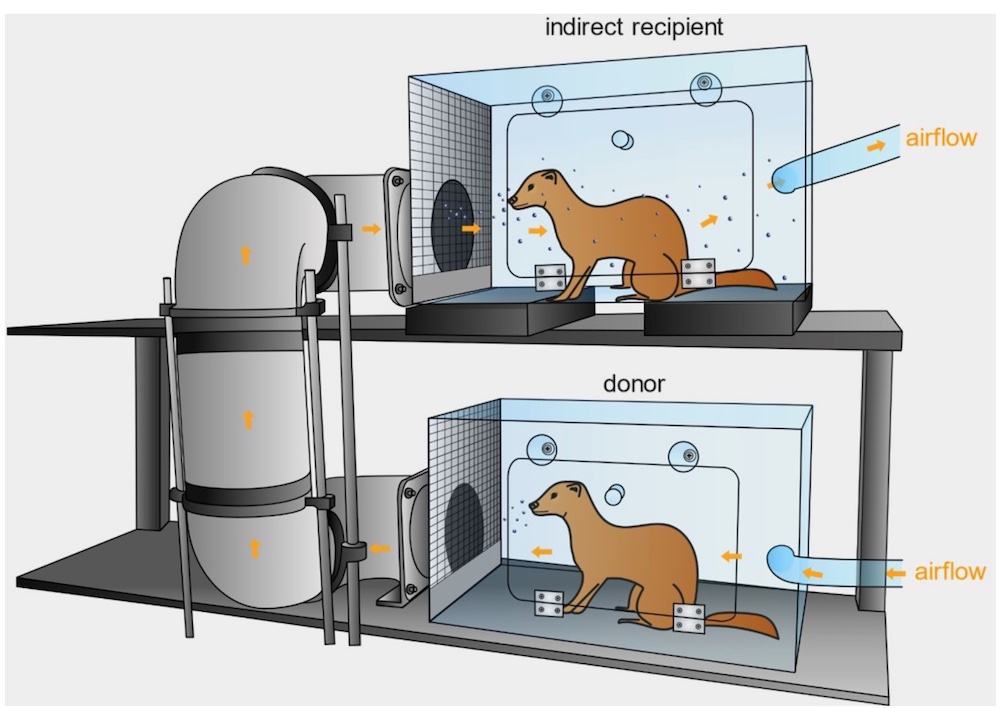

Caged animals such as ferrets have infected other ferrets connected only by a shared air duct with lots of right angles to capture large particles, illustrating once again the role of aerosols in transmission.

And researchers have found COVID-19 trapped in air filters and building ducts in hospitals with COVID-19 patients. Heavier droplets can’t float into those areas.

3. Talking is the new sneezing. People don’t have to be coughing or sneezing to spread COVID-19. Asymptomatic carriers, which account for up to 50 per cent of infections, can spread the coronavirus just by talking and breathing. One study found that just one minute of loud speaking produced upwards of 1,000 small, virus-laden aerosols micrometres in diameter. They can float in the air for at least eight minutes.

4. Wind and sun chase it away. Transmission of the coronavirus doesn’t happen as frequently outdoors as it does indoors. That’s because the wind disperses or dilutes the aerosols, or ultraviolet radiation zaps them. (In one experiment, a room with direct sunlight dispatched a COVID-19 aerosol in six minutes; in contrast the virus survived 125 minutes in darkness.) After the Black Lives Matter demonstrations last year, many researchers predicted massive clusters of COVID-19. That didn’t happen. A beach with lots of people is much safer than any Amazon warehouse.

5. Hospitals, even with PPE, are vulnerable. COVID-19 outbreaks have happened frequently in hospitals and long-term care facilities despite strict contact and droplet protection and the use of PPE designed to block out droplets instead of aerosols. More than 84,000 health-care workers in Canada have contracted COVID-19.

6. Aerosols hang in the air a good while. In lab experiments, researchers have created aerosols that have remained infectious in the air for up to three hours. Infectious aerosols have been found in the rooms of COVID-19 patients as well as their cars. Wiping down surfaces doesn’t eliminate the threat, because you can’t wipe down the air.

7. Much research points to aerosols. According to the Lancet researchers, they looked but couldn’t find any study that provided strong or consistent evidence to refute the hypothesis of airborne SARS-CoV-2 transmission.

To date, there isn’t a lot of research that actively supports droplets in the air or on surfaces as the primary cause of infection. Since the 1930s, medical researchers have assumed that large respiratory droplets in the air or on surfaces accounted for most if not all respiratory infections. Because of this spray-borne dogma, researchers missed the airborne transmission of measles and TB for a long time.

In sum, the Lancet researchers concluded that “it is a scientific error to use lack of direct evidence of SARS-CoV-2 in some air samples to cast doubt on airborne transmission while overlooking the quality and strength of the overall evidence base.”

The nations that figured right

Many countries that successfully battled COVID didn’t wait for researchers like those in the Lancet to tell them what to do. From the onset, those in charge just assumed that aerosols played a major role in COVID-19’s spread.

Taiwanese officials, for example, took their clue by watching videos of Chinese doctors at work in Wuhan hospitals at the beginning of the pandemic. They all wore respirators (N95 masks). That was enough evidence for the Taiwan government to focus on aerosol transmission.

In China, authorities still assume that flushing toilets, which disperses aerosols, can also be a route of transmission because COVID-19 typically infects the bowels and human excrement.

Japan identified aerosols as a problem when it sent trained professionals to inspect the afflicted cruise ship Diamond Princess.

Although masked and protected for droplet exposure, these officials came down with COVID-19. Japanese researchers then adopted a highly effective public health campaign: avoid the three C’s: close contact, close quarters and crowded places. Subway trains, for example, opened their windows while masked commuters were told not to talk on the trains. Likely as a consequence, Japan, which has the world’s oldest population, never witnessed anywhere near the death rates of Canada.

Slow on the draw

The spray-borne and aerosol-borne debate illustrates another feature of this pandemic: the failure to act early with incomplete evidence during an emergency.

Throughout much of this pandemic, the medical community, fearful of being wrong or making mistakes, has often waited for overwhelming evidence to make decisions. (No military leaders fight a battle that way unless they want to lose.)

Encumbered by this herd thinking, public health officials have responded too late to key developments such as the importance of masks, aerosols, transmission in schools and the emergence of more infectious variants. Not surprisingly, public health outsiders and complexity experts such as Zeynep Tufekci, a U.S. sociologist, carried the burden of sounding the alarm about the importance of aerosol transmission and masks.

Minimizing risks in the face of uncertainty has not served the goals of public health during the pandemic, noted U.K. epidemiologist Deepti Gurdasani in a recent series of tweets.

“If we were to wait for data to accumulate before taking any action, when risks are high in the midst of a pandemic, we would always be firefighting, rather than preventing,” noted Gurdasani.

“I'd rather have advised caution, and be wrong, rather than minimized risk without basis and be wrong,” she added.

Uncertainty shouldn’t mean inaction. “It means we consider the space of possible outcomes and risks, try and reduce risk and uncertainty to the best extent we can — especially when the risks are large. So many countries in Southeast Asia, Asia understood this early on. We still don't,” said Gurdasani.

So here’s what we should do right now, without any more hemming and hawing and delay. Pay attention to ventilation — the kind that spreads the coronavirus and the better version that lowers its circulation. Know that close contact in closed quarters is ideal for this coronavirus to spread, and wearing a mask under such circumstances is not enough to stop it. Get even more serious about the quality of masks you wear and the distance you keep from others, spending as little time as possible collected with random others crowded indoors.

The evidence points extremely strongly to the fact that aerosols exhaled and floating, not droplets sneezed and splattered onto surfaces, are advancing this pandemic. And given the rise of the variants, this will likely remain a critical issue for some time to come. ![]()

Read more: Coronavirus, Science + Tech

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: