[Editor’s note: When it comes to the big picture on pandemics, Tyee contributing editor Andrew Nikiforuk wrote the book. It’s called Pandemonium: Bird Flu, Mad Cow Disease and other Biological Plagues of the 21st Century. Written in 2006, it’s unfortunately very much of the moment and predicted the current pandemonium. Looking at the current COVID-19, Nikiforuk offers these lessons for people in charge, and not.]

As local governments try to implement their pandemic preparedness plans, they will rudely discover what Thomas Glass, an American public health researcher warned years ago: “Disaster planning does not go as planned.”

Communities under biological attack often respond collectively and creatively, argues Glass. They normally do so without emergency professions in the neighbourhood.

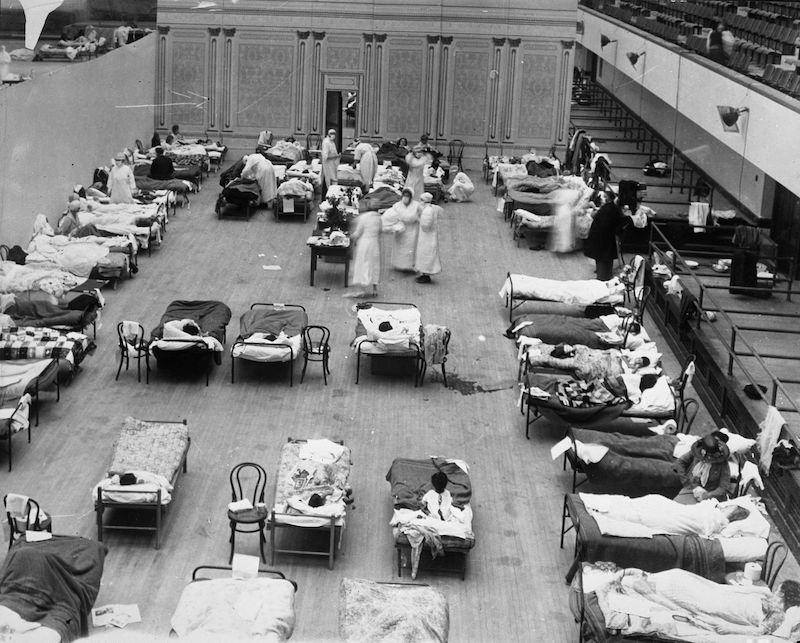

In the absence of white coats, they will form spontaneous groups that will establish their own roles, rules and leaders. Government plans that don’t recognize and support the public as first responders and as the only auxiliaries that truly matter will fail and fail miserably. During the 1918-19 pandemic, the public fed and nursed the sick at home and then buried the dead. The next severe pandemic will be no different.

Though the impact of COVID-19 is, for now, projected to be far less catastrophic than the Spanish Flu, we are already seeing economic shock, a social collapsing inwards, and, based on a mortality rate of one to two per cent, the prospect of 500,000 to one million deaths in North America.

Here are some lessons taught by past pandemics.

Cities with strong civic traditions and public health programs respond better than uncivil places.

During the 1918 pandemic, Philadelphia suffered horribly while San Francisco did not. Philadelphia, a city led by crooked mayor and inept public health authorities, abandoned its most vulnerable and dumped the dead outside police stations while proclaiming, “There is no cause for alarm.”

In contrast San Francisco, which had recovered from an earthquake, marshalled community resources. When the schools closed, teachers volunteered to serve as nurses, gravediggers and telephone operators. The city focused on containing the invader as opposed to corralling panic. Every citizen wore a mask and pitched in.

Pandemics and disasters have never been equal opportunity events.

They generally target the most vulnerable — or the very people that professionals often leave out of their plans such as the elderly, prison inmates, the homeless and Indigenous communities.

People respond creatively and resourcefully to tragedy and natural disaster.

Panic is the exception, not the rule, among ordinary people. The same, however, cannot always be said of professionals as the Katrina hurricane debacle and the handling of SARS in Ontario demonstrated so well. Ordinary people react the way they live as parents, co-workers, neighbours, and church and synagogue members. In other words, pandemic planning must treat civilians as competent allies.

Hospitals will be on the front lines of any pandemic and are often the first institutions overwhelmed by a surge in numbers.

Quite often they can amplify the disease, as has been the case in Italy. Citizens can support their hospitals by avoiding them. They also need to request tests from mobile units, not hospitals.

The outcome of a pandemic or a disaster is not set in stone.

It will be shaped by complex interactions of citizens and authorities and an unforeseen constellation of events. Transparent planning that engages the local community improves the outcome. It’s okay for civilians to improvise. ![]()

Read more: Health

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: