In February of 2017, Canadians got official word that Justin Trudeau’s campaign promise to end “first-past-the-post” federal voting was moot, kaput, thoroughly broken.

The election results are laden with irony, because Trudeau’s Liberals, had they kept their word and given voters a different electoral system, might find themselves in a stronger position.

In seeking to lead a minority government Trudeau will need to build bridges to avoid being toppled. He would have benefited from a voting system that handed him more political capital at the starting line, a clearer claim that his party deserves to speak even for voters who supported other parties.

Recall that when the 2015 election began, Trudeau and his party were in third place, lagging well behind the NDP. He fought to the front by promising deficit spending and other centre-left policies, and by projecting progressive values such as feminism and environmentalism. The fight in 2015 was for the anybody-but-Harper vote and Trudeau competed superbly, in part by pledging a voting system that would put more Greens and New Democrats in Parliament.

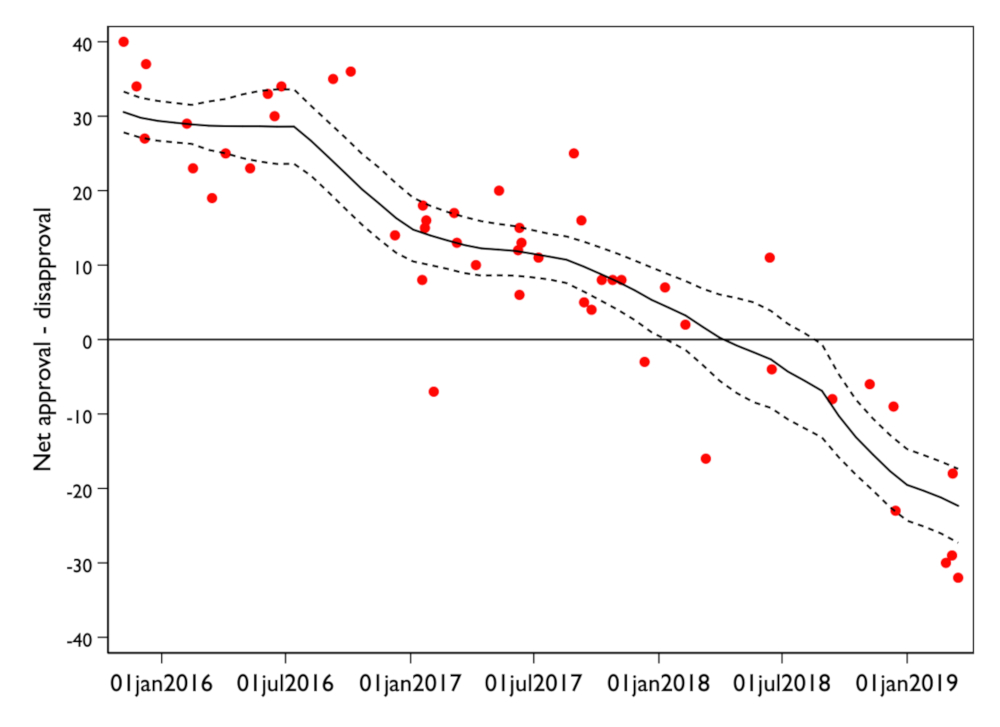

Trudeau’s honeymoon lasted more than a year, his approval rating reaching 50 per cent. Then, as UBC political scientist Richard Johnston has written, “the rot set in.” Trudeau’s ratings began sliding down, down, down. What triggered it?

Johnston finds Trudeau’s poll numbers “from early December 2016 on are clearly at a lower level than they were as late as November of that year. It is tempting to impute the shift to the fiasco that concluded the Electoral Reform Committee. Although the issue was not central in many voters’ minds, the outcome was the first high-profile broken promise. At this point, the Trudeau narrative started to shift.”

If Johnston (an expert on electoral systems) is right, it throws doubt on the Liberal claim that few Canadians really cared much about electoral reform.

More important, Trudeau not only broke a big promise, he broke a powerful spell. His “narrative” had been about a prince leaving behind his virtuous youth to fill people’s desire for a new kind of politics. He’d run as a sunny-ways idealist. On electoral reform, he was stepping out of costume, telling a different story of the self-interested cynic — a political narrative all too familiar.

Trudeau’s ruthless calculus included sacrificing one of his own. It fell to a young, female, Afghan Canadian Liberal MP, Maryam Monsef, to handle the delicate electoral reform file, and her own party made the job miserable. The Liberals created a multi-party committee to study what to do, but immediately drew charges it was stacking it in its favour.

When the committee’s majority report recommended proportional representation, Liberal members refused to sign on and recommended abandoning a 2019 deadline for reform.

As Monsef moved from one mess to another, she endured humiliation and even had to apologize at one point in the House. By the time she was mercifully shuffled to a new cabinet role in January 2017, it was clear Trudeau and his party had no stomach for electoral reform.

“Hey, how about we change our elections” is a complex conversation to conduct within any democracy. If Trudeau was serious about it, he needed to put a lot more effort and skill into making the argument, Johnston told me in an interview today.

“Part of why the electoral reform process failed,” Johnston said, “is the Liberals were unwilling to argue for their original position.” Perhaps insiders of the self-styled “natural ruling party” concluded that the party would do still better by raising the price of defection.

So here we are 34 months later, and Trudeau has eked out a chance to form a minority government. Let’s muse (and muse we must because scientific analysis is impossible given the variables) about whether he helped or hurt himself by killing electoral reform.

Recall that Trudeau had never touted proportional representation. He signalled his preference was a ranked ballot, which allows voters to mark their first, second and third choice candidates. If no candidate wins a majority, the person with the fewest first-place votes is dropped from contention and the second-place choices they received are then counted, and so on until one candidate wins a majority.

Suppose, despite Trudeau’s own preference, Canada had ended up with the proportional representation system the parliamentary committee’s majority report recommended. That would have assigned seats, basically, in proportion to votes cast.

In that case, the Liberal number of seats today would be much lower. However, the Liberals would have the most MPs in the left-of-centre coalition government that would now be ready for assembly.

Would it chafe the Liberals to have to share power that way? It shouldn’t if Trudeau was authentic in 2015 when he embraced environmental and wealth-sharing principles shared by Greens and New Democrats. Now, as leader of a pro-rep-delivered coalition government, he’d enjoy firm, formal support from his former foes in advancing those aims. He therefore would be liberated to offend some of his right-wing Liberal constituents and match his efforts more closely to the vision he espoused in 2015.

What if this election had been decided by a ranked ballot approach to voting?

UBC political scientist Kathryn Harrison told me, “Voters may have been more willing to put the Greens or NDP as their first choice, but if those parties didn’t get enough first choice votes, and the Liberals were those voters’ second choice, I’d expect the Liberals to be net winners, not losers.”

“On balance, I’d expect the Liberals to be beneficiaries of a preferential ballot, because the Conservatives would not do so well on second choices,” she said.

Johnston agrees with that analysis. In other global jurisdictions “historically the beneficiary of a ranked vote has tended to be on the right,” Johnston said. But in Canada, the more parties with significant common policies are competing on the left.

Distribution of votes among parties would not have changed much with a ranked ballot, Johnston predicts, drawing on the research he pores over. But the Liberals could well have ended up with more seats.

In any case, let’s assume ranked ballot voting delivered Trudeau roughly to the spot he now awkwardly inhabits. Namely, having to go hat in hand to the New Democrats, Bloc and Greens to convince them not to bring down his government. Forging that trust would be much easier had he not lied about electoral reform to begin with. Now how embarrassing might it be should the parties require, in return for their support, making good on his pledge to do away with first past the post.

Jagmeet Singh has said the issue is still on his agenda.

“In a minority Parliament, I would consult with our caucus and advocate for the inclusion of proportional representation as a condition of any alliance or support for a minority government,” he said during the campaign.

That will be an interesting conversation between Singh and Trudeau.

When Trudeau emerges from the discussion, he will need to summon the hopeful charm that made him prime minister four years ago. Trust me, he’ll say to Canadians. This time, trust me. ![]()

Read more: Election 2019, Federal Politics, Elections

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: