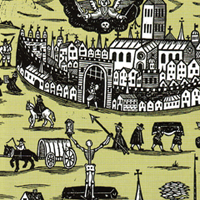

- Dread: How Fear and Fantasy Have Fueled Epidemics from the Black Death to Avian Flu

- Public Affairs Books (2009)

This is a very timely book. While anxiety rises and falls over swine flu, Dr. Philip Alcabes, a public-health expert in New York City, gives us some much-needed perspective.

Dread is a history of cultural and political responses to pandemics and epidemics -- words we still can't define.

"There’s no constant, neatly defined thing that we can all agree is an epidemic," Alcabes says. "Nor do we agree on how to describe one." The World Health Organization is no better at defining "pandemic." As long as such definitions are hazy, they become convenient ways to promote various social and political agendas.

Still, Alcabes finds that epidemics differ from routine illnesses in three ways. They are physical events, microbial disturbances in the ecosystem that affect human wellbeing. They can trigger a social crisis by disrupting the stability of communities. And they are narratives that, like any story, explain the world as a struggle between good guys and bad guys.

Plague as moral judgment

The epidemics of ancient times were supposed to be the result of divine annoyance with human behaviour. Oedipus angered the gods by his unknowing incest, but his people of Thebes suffered pestilence for it.

By the 14th century, epidemics were seen to be divine punishment for bad behaviour, but now God was angry with unpopular groups. The urban poor, who caught plague more readily than the rich, clearly deserved it. So did the Jews, who were often slaughtered in huge pogroms before they ever got a chance to catch bubonic plague.

In later epidemics, like cholera, the poor were again blamed for their illness. Now the cause of their misery was their tendency to live in filth and ignorance, combined with feeble constitutions resulting from drink and dissipation.

Plague as pretext for state intervention

Alcabes argues that since at least the 14th century, disease outbreaks have stimulated the growth of the modern state. If the ungodly were provoking divinely sent plagues, then the state and church needed to persecute the impious and sinful. If the bad habits of the poor were making them sick, then the state must control their licentious behaviour. Fear of epidemics, like fear of terrorism, gave the state enormous leverage against its own people.

So by the mid-19th century, when the germ theory of disease began to take hold, governments felt a duty to extend their powers still further, enforcing new levels of sanitation on the poor.

Surprisingly, Alcabes argues that the germ theory actually succeeded too well. Germs became the only cause of disease. The social conditions under which disease flourished were increasingly ignored. (Rudolf Virchow, the doctor who saw politics as the practice of medicine on a large scale, was a germ-theory skeptic). Public health experts relied increasingly on promoting sanitation, and again blamed the dirty, ignorant poor for getting sick.

Plague as pretext for racism

In the squalid decades of immigration to North America, virtually every immigrant group was blamed for carrying some alarming new germ. After the cholera-carrying Irish of the 1840s and 50s, it was the Jews bringing TB and the Italians bringing polio. Blacks, of course, were famous carriers of syphilis.

Blaming minorities for disease helped to stoke North American racism even as medical science began to understand how bacteria and viruses operate. The American eugenics movement, designed to prevent the "inferior" from reproducing, was the direct inspiration for similar Nazi legislation against homosexuals, the mentally ill, and racial minorities. Hitler praised the Americans for leading the way.

Alcabes argues that these social responses were most intense in the cases of epidemics. The routine background noise of endemic disease has never stirred the same kind of anxiety. The diseases that really kill us, like the auto accidents that also kill us by scores of thousands every year, just don't register.

Likewise with gunshot deaths, which in the US have averaged about 30,000 a year since 2000. (The toll since 1962 has been well over one million Americans). Except for the occasional "shooting spree," such deaths draw little attention and no effort to prevent further mortality.

Instead, we worry about bad sexual behaviour that leads to HIV/AIDS. We condemn people with TB who neglect to take all their medicine and thereby help the bacterium gain resistance to antibiotics.

Plague as anything we don't approve of

Now, says Alcabes, the fear has shifted from the diseases themselves to conditions that increase "risk" of contracting them: obesity, unsafe sex, and so on.

And of course we worry (Alcabes thinks needlessly) about H5N1. Statistically, he has a good argument. Only one of the last four or five influenza pandemics was really deadly, and H5N1 could, like H1N1, become highly contagious but not very lethal at all.

As with early plagues, we tend to look for someone to blame for the spread our current epidemics: Indonesia's health minister, and the ignorant villagers of her country, take the blame for H5N1. An American multinational pork producer in Mexico takes the blame for swine flu.

In these cases, as with early plagues, we may feel that our superior knowledge of the threat removes the issue of choice: To survive, we need to plan, to prepare, to alert our neighbours... and if necessary, to impose emergency rules on the ignorant. Every new case, every new fatality, gives us a stronger argument for imposing those rules and punishing those who break them.

On these points, Dr. Alcabes provides a useful perspective. Yes, it's a scandal that we don't attack the endemic diseases with the energy we devote to "virtual" pandemics. Yes, it's folly to ignore preventable deaths from accidents and violence. Yes, we worry about "risk" conditions at home while ignoring real diseases elsewhere.

And he is certainly right that we have ignored the social context that gives bacteria and viruses their big opportunity. While he might not say it as bluntly, much of what we consider hygiene is little more than an attempt by the anxious middle class to control the dirty, lawless, sexually profligate poor.

In his blog, Alcabes is currently arguing that a real healthcare system must be universal if it is to work at all. In the US, many still consider this idea to be heresy.

After 2500 years, we still think sudden disease outbreaks must be someone else's fault: sinners, foreigners, poor people, communists. Alcabes makes a strong case that when a new disease discovers us, we ourselves invite it in.

Read more: Health