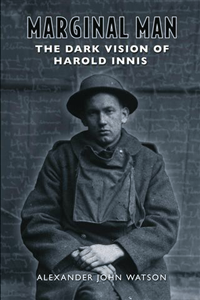

- Marginal Man: The Dark Vision of Harold Innis

- University of Toronto Press (2005)

- Bookstore Finder

Harold Innis lives in the shadows of Canadian history. If we know him at all, it's as a precursor of Marshall McLuhan and some vague kind of early nationalist. But for 30 years he was the country's leading economist and historian, an influential academic and a scholar who anticipated the hypertextual age of the web.

A recent book about him brings Innis back to life, and reminds us that the issues he dealt with are still with us. Marginal Man: The Dark Vision of Harold Innis, by Alexander John Watson, portrays a man more radical, and more conservative, than any other scholar of his time or ours.

The metaphor of the margin was ingrained in Innis's thought: the periphery, not the centre; the province, not the capital; the blank edge of the page, not the text. Millions of Canadians have seen themselves as marginal, distant first from the British Empire and then from imperial America. A century ago, ambitious young Canadians moved to London to advance their careers. Now they move to New York or L.A. Only then do we here at home see them as truly successful.

Early in his life, Innis took one enormous step beyond that parochial view: he stayed home. Once taken, that step led him farther than most of us have dared to go.

He had grown up in rural Ontario, a farm boy who graduated from Woodstock Collegiate Institute (now McMaster University). He then enlisted in the army in 1916. As a signalman he often worked beyond the safety of the trenches, and he suffered a shrapnel wound that took seven years to heal.

Convalescing in England, Innis completed his master's degree through Khaki University, and returned to Canada before the war's end. He thought of a career in law, but decided he needed to know more to qualify himself. So he went to the University of Chicago for a PhD in economics, and returned to Canada as a young professor in the University of Toronto's department of political economy.

Ideas arose from 'dirt research'

Canada in 1920 was a marginal country: a strip of English, Irish, Scots and Quebecois, living close to the U.S. border. Innis chose to explore the economics of this country, doing "dirt research" by travelling from coast to coast (often at his own expense).

He talked to loggers and miners, trappers and farmers, and learned that a geographic logic underlies the country. The natural trade routes run east and west, along the rivers and lakes -- though Innis himself had to fight for Ottawa to create maps that would show these routes.

His research taught Innis that empires acquire provinces, and the provinces in turn supply the resources to sustain the empires. What's more, empires become blinded by their own success. Their vision of the world seems self-evidently correct and the source of their achievement.

Innis thought the real insights come from the provinces, from the margin. Canada should therefore understand itself and the world in Canadian terms -- not in terms of some ideology imported from Europe or the U.S.

This was not the daydream of a jingoistic nationalist. As Innis read history, the marginal societies have always had a clearer understanding of the world than their imperial neighbours.

The marginal Greeks rejected imperial Persia, and founded western civilization. The marginal Macedonians conquered Greece and Persia, and in turn fell to the marginal Romans. On the margins of medieval Europe and imperial Spain, England rose to greatness around the world until marginal America became the new empire.

Imperial academia rejected

Some say that academic politics is so vicious because the stakes are so small. Innis, a brilliant academic politician, saw the stakes as enormous -- nothing less than the fate of the nation and western civilization.

To import ready-made philosophies and ideologies from the imperial centres, Innis thought, would subvert scholarship and cripple the nation. So he fought for Canadians to be appointed to professorships in Canadian universities, though British and American academics might bring more prestige. (The same issue arose in the 1960s as Canadian universities and colleges expanded to serve the baby boomers, and Americans streamed in to meet the demand.)

He defined academic freedom in terms few academics today would dare to support. For Innis, the university must be completely independent of the society that supported it. Its scholars must be truly disinterested, pursuing knowledge and truth regardless of political consequences. They must develop their view of the world from their own research, on their own ground.

To pursue the implications of this insight, Innis moved from books on the CPR, the fur trade and the cod fishery to explorations of the communication systems of ancient and modern empires. But while he pursued this project through the 1930s and 1940s, he was also working hard to keep Canada marginal.

His studies of Canada's economy made him an academic star, influential in business as well as post-secondary institutions. He recruited young Canadian scholars to the University of Toronto, rather than Brits or Yanks who would bring their imperial baggage with them.

He also fought to keep the university, as an institution, as independent as possible of political trends and fashions. The scholar's role, as he saw it, was to serve the state by providing accurate and unbiased knowledge. Moreover, it would be knowledge gained from thousands of years of history.

'Royal commissioner from hell'

As Watson observes, this was a political position, and Innis was an intensely political man. But his deliberate detachment from everyday political events meant he won battles but lost the war. He could find no made-in-Canada solution to the Depression, while his colleagues imported Keynes or Marx. (When they got into political trouble, though, Innis defended them fiercely.)

The Second World War led to countless academics leaving the universities for military service or work in the bureaucracy. Innis stayed where he was, defending liberal arts programs when they might have been cut to help the war effort. Looking beyond immediate problems, Innis ensured that veterans had a university to return to.

While he fought for university autonomy, Innis fully supported the idea of the scholar-advisor to the state. Despite an enormous workload, he also served on three royal commissions. His standards, says Watson, made him "the royal commissioner from hell" -- rigorous, uncompromising, and determined to tell the government exactly what he thought.

As he moved beyond orthodox economic history, it was to larger issues that "dirt research" couldn't illuminate. Instead, Innis plunged into classical studies, using other scholars' work to understand the origins of empires and how communications sustained those empires.

Hypertext on paper

Watson describes Innis at work, surrounded by semicircles of books on the floor, and piles of papers on every surface. He organized his information much as we do on our computers...but Innis had no computer.

Instead he pencilled notes in the margins of the books he read, and transcribed relevant passages onto paper. He made primitive photostat copies of his notes, giving him white text on a black background. He then literally cut and pasted these notes into a gigantic manuscript. From this he carved articles and books that now look like a rough form of hypertext.

As today's web-surfing students should know, his hit-and-run research methods began to look dangerously like plagiarism. Innis could get away with it, but it was not a method he could teach his students.

Just as hypertext baffles many people accustomed to sequential, linear argument, Innis's late works baffled more readers than they enlightened. He also startled cold-war North America by arguing that the American Empire, not the Soviet Union, was the real danger to world peace. Russia, he claimed, historically sought stability and conservatism; America had inherited the western European drive for change at all costs. Watson argues persuasively that this was a logical progression of Innis's views, not a mid-life lapse into ideological fantasy.

Innis on war-mongering, circa 1948

Innis's research findings, however dubiously achieved, put him far ahead of his time. Consider a paragraph written in 1948:

"Formerly it required time to influence public opinion in favour of war. We have now reached the position in which opinion is systematically aroused and kept near boiling point. … [The] attitude [of the U.S.] reminds one of the stories of the fanatic fear of mice shown by elephants."

Innis's was a dark vision because he saw the "mechanized" media as replacing ordinary face-to-face conversation. Such conversations since Socrates had helped equip free individuals to build free societies by examining many points of view. Instead we were to be increasingly dominated by a single point of view in print and electronic media: the view of the imperial centre.

Would Innis have been cheered by the rise of the Internet and its millions of online conversations? Probably not. As Watson observes, the advent of the web is eradicating margins. The blogosphere simply multiplies the number of outlets for the same few messages.

If we are to hope for new insights and criticism of the imperial centre, Watson says, we will have to turn to marginal groups: immigrants, women, gays, First Nations, francophones and Hispanics. They are as trapped in the imperial centre as the rest of us, but they still maintain a healthy alienation from the centre's self-referential follies.

And just as Innis studied half-forgotten early thinkers, says Watson, we should study those on the margin of time: "Returning to the great thinkers of our past to see if they are still speaking to us across the years."

Harold Innis was ahead of his time 60 years ago. Perhaps we are ready to understand him now, but we won't know until we listen to him again.

Crawford Kilian is a frequent contributor to The Tyee.

Related articles: For Harold Adams Innis:

The Bias of Communications & Monopolies of Power, click here. For Harold Innis: An Intellectual at the Edge of Empire, click here. For Harold Innis: A Contemporary Perspective, click here. ![]()