As a junior biologist working for the Fraser Valley Conservancy, I’ve been working on putting together a map of our frog and salamander observations. So much of this data is collected by citizen scientists, who submit their photos or videos to programs like iNaturalist or Fraser Valley Conservancy’s Frog Finders program.

The conservancy focuses a lot of our efforts on amphibians. We do annual surveys in the spring, searching wetlands for frogs and salamanders. We also make efforts to protect and enhance their habitat. But before any of these activities can happen, we need to know where they are. That’s where all these amphibian observations come in.

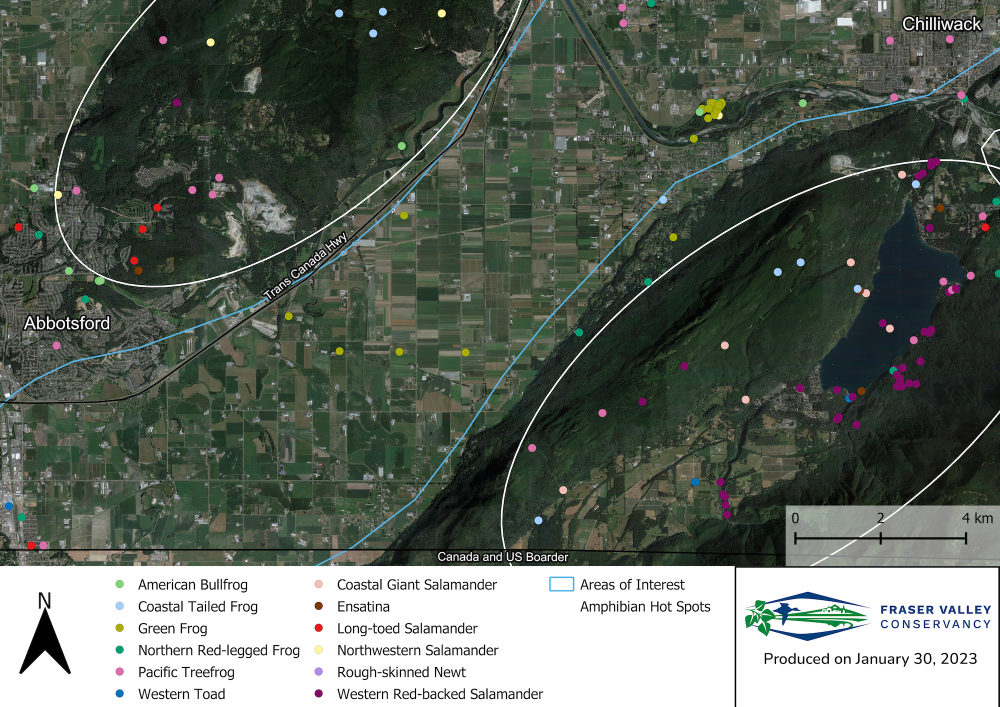

Thousands of the points on the map started as photos, videos and audio clips that were submitted by citizens — and I’m hoping that if you live in Metro Vancouver, I can convince you to do some citizen science, too. Looking through all the data, you learn how much of an impact a single photo can have.

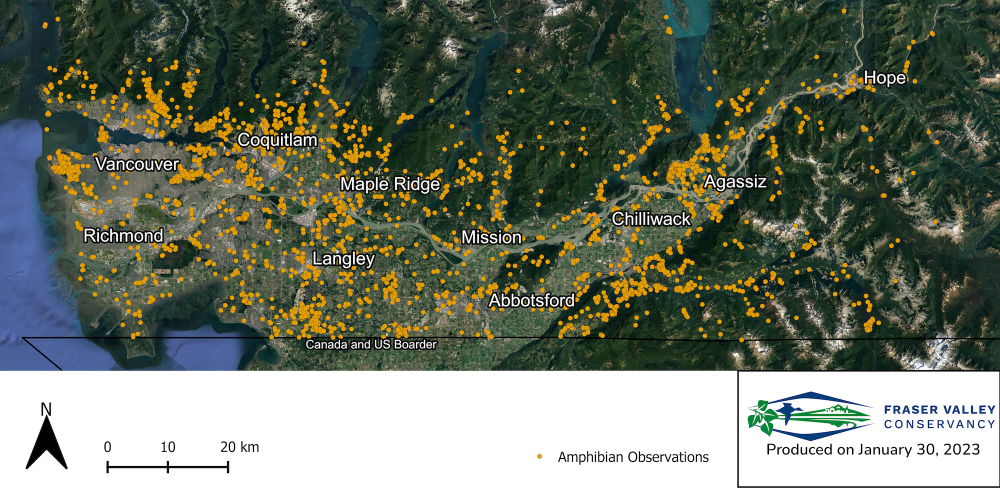

When I first began making maps, I felt like the whole map was covered in orange dots, each representing an amphibian.

Once I zoomed in, I realized there are huge areas with little or no amphibian observations.

It seemed impossible that only a handful of observations have been made in some of these areas, like Sumas Prairie, an area that was covered in water only a hundred years ago. When this water was drained, surely these amphibians persisted. So where are they all?

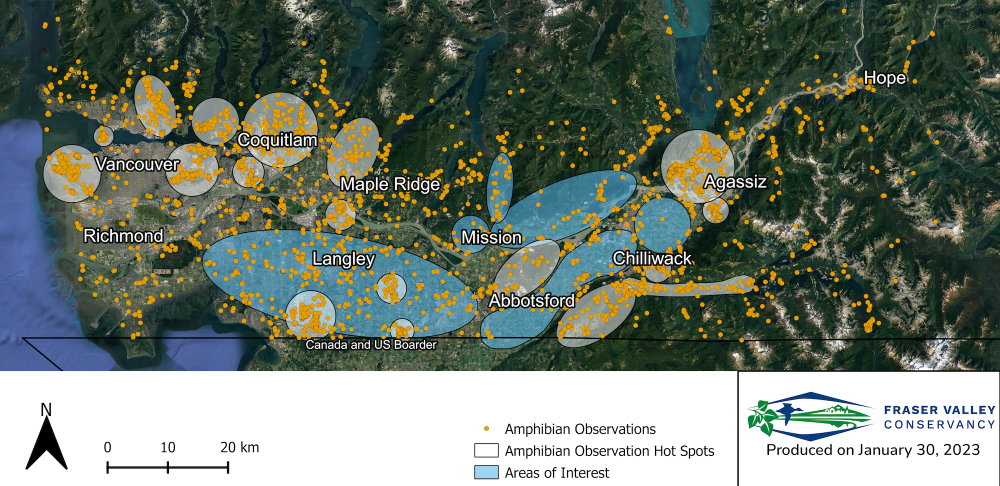

I found that huge portions of the Fraser Valley are lacking amphibian observations, but other portions are rich with amphibians. From here, I was able to identify “amphibian observation hot spots.” These are areas where many amphibians have been sighted and reported. I also identified areas of interest — where there haven’t been many observations but could be great for amphibians. Many of the hot spots surround public parks or protected areas. Whereas many of the areas of interest contain private land.

Looking at the hot spots, it might seem like there are more amphibians there compared to outside them — but this isn’t the case. They just haven’t been reported as thoroughly as they have inside the hot spots.

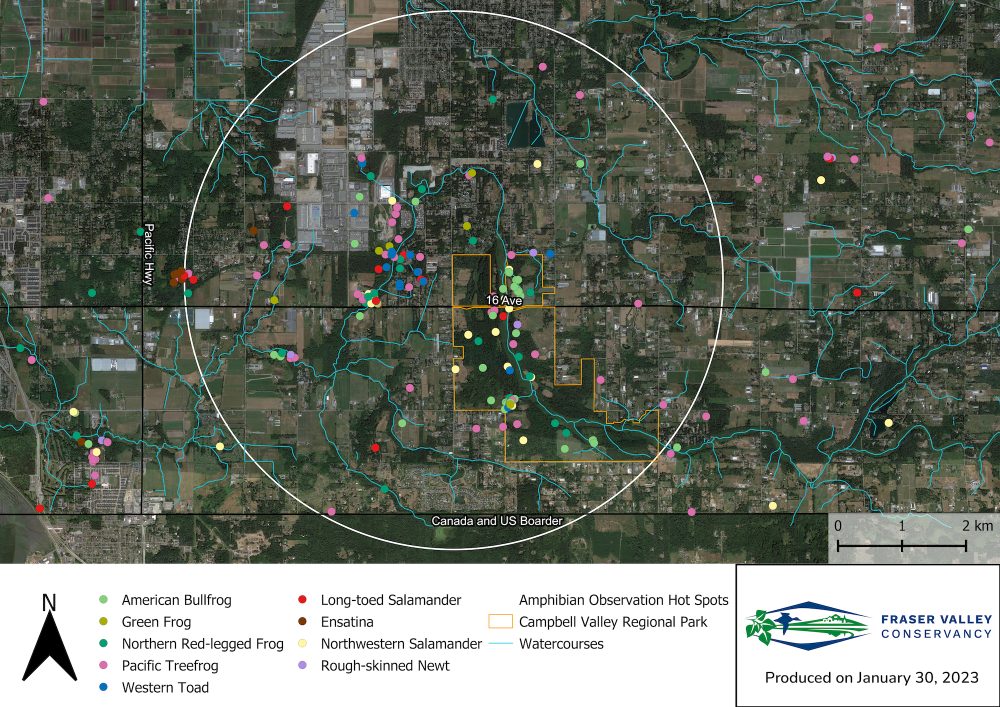

Campbell Valley Regional Park, for example, has so many different observations inside the hot spot, but way fewer outside. The amphibian habitat doesn’t stop at the edge of the park. It continues through the farmland and residential areas and so do the amphibians. Amphibians use the waterways, and you can see that the water travels way beyond the hot spot.

Sightings of frogs and salamanders just aren’t being reported outside the park. Lots of people think that reporting their wildlife sightings outside of parks isn’t important, but it is!

Amphibians are important to their ecosystems and sensitive to changes, so biologists need to know where they are. Even if its a poor-quality audio clip or a blurry photo, its evidence that amphibians are in an area, and that’s good news.

When there aren’t any amphibians, it’s a sign that the area might be polluted or lack healthy habitat features. Some amphibians, like western toads, need a mix of healthy forest and wetland habitat. For toads to survive they need these habitats to be connected so they can move between them.

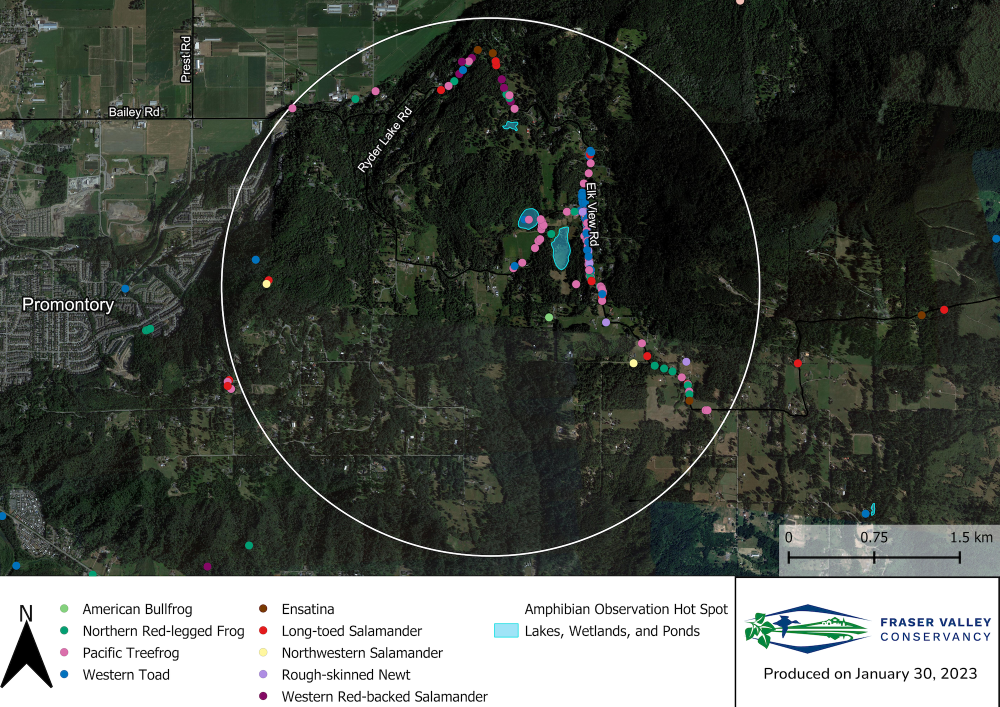

Ryder Lake provides a great example of how a picture can make a big difference. Residents of the community noticed toads dying on the roadways that sit between the forest and the wetland. They reported these sightings and reached out for help, which got the conservancy involved.

Because of these reports from the community, the FVC was able to tell which location along the road would be the best place to build a tunnel for the toads. Projects like this make a huge difference for the toads’ survival and wouldn’t be possible without those initial citizen reports.

So many strategies for protecting wildlife begin with citizen science data. While there are a decent number of observations in parks and protected wildlife areas, there are shockingly few on private land. It’s not that amphibians aren’t there, but that they aren’t being reported. That’s where you and your photos come in. Submitting photos to citizen science programs helps to fill the map and can result in real change.

Circling back to Sumas Prairie — there are waterways all throughout the prairie that amphibians might be using but still have no reports. But citizens like you can help find them and fill the map up with as many observations as possible, allowing biologists to protect these amphibians and their homes.

The current lack of observations is, in some ways, a great opportunity. I get excited about how I could be a part of discovering where these amphibians are, and that’s true for everyone. There could be new populations of frogs or salamanders that no one knows about. You could even discover a population that needs help.

Join me and the Fraser Valley Conservancy in discovering and protecting amphibians by submitting your photos or videos through the Frog Finders form today — or the next time you’re out and about and see a frog. ![]()

Read more: Science + Tech, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: