The seawall was my first Vancouver love. I’ve spent many Sunday afternoons whipping around Stanley Park on my bike, taking in the forests, beaches and mountains while spotting harbour seals hunting in the kelp beds just offshore.

It’s still my personal escape from the noise and chaos of the city — without having to leave the city at all.

Imagine my surprise then when I watched local videographer Uytae Lee make a case for tearing it down. (Here's his video.)

In his video, Lee highlights the seawall’s impact on intertidal habitat, the constant need for expensive repairs and the fact that it will be rendered useless by sea level rise. There are piles of academic papers espousing the harm seawalls cause to shoreline habitats, including one of mine.

But these issues don’t pertain to our seawall, right? Ours isn’t like the others. It’s different. But as I watched the atmospheric rivers of 2021 rage on, the Vancouver seawall — and my relationship with it — began to show cracks.

Rosy beginnings

Construction of the seawall in Stanley Park began in 1917, as people started noticing that the ocean was slowly washing the park’s sandy cliffs into the sea. Stonemason James Cunningham had the idea of putting a wall between the land and the ocean and thus, the seawall was born. By 1980, the full loop around Stanley Park was complete. Locals and tourists alike flocked to its unique setting and spectacular views.

Today, the seawall is the longest continuous waterfront pathway in the world, drawing millions of visitors and single-handedly supporting a plethora of bicycle rentals in the West End. It’s an icon of Vancouver and symbolizes the city’s commitment to having a waterfront accessible to all. Glowing ratings from Tripadvisor, the New York Times and my visiting mother all make it clear: people love this thing.

And so do I. Where else in a major city can you walk uninterrupted along the waterfront for a sprawling 22 kilometres? The seawall is part of Vancouver’s unique culture; one of getting outside, enjoying the weather and connecting with nature.

That doesn’t mean it should stay.

Red flags

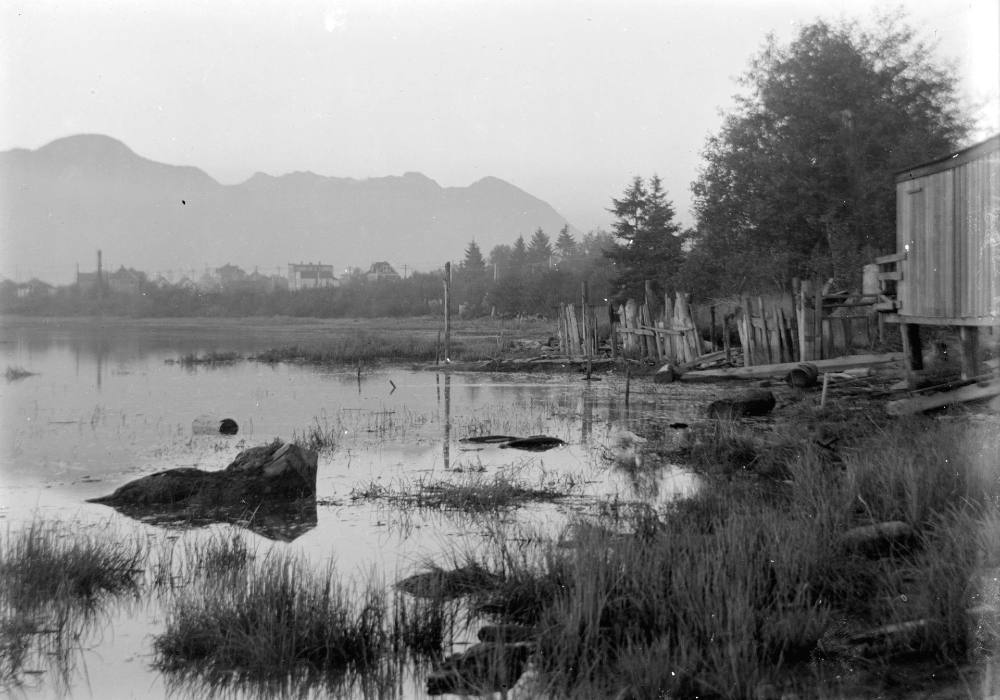

Prior to colonization, Vancouver’s coastline was a hotspot for aquatic life. The tidal mud flats around what is now False Creek supported a robust shellfish population harvested and stewarded by local Indigenous communities. Eelgrass meadows, known as “nature’s nursery,” provided safe havens for juvenile salmon and herring making their way out to the Salish Sea. Along the shores of what is now Stanley Park were large swathes of sandy intertidal habitat — created by erosion of the sandstone bedrock — that supported starfish and crustacean populations. These were complex, dynamic ecosystems, damaged heavily by the addition of the seawall.

In False Creek, the “boggy” mud flats were deemed a nuisance to development and filled in for industrial and subsequent residential use, creating a homogenous, desolate habitat today. Gone are the eelgrass beds, the salmon streams and herring spawning grounds. In their place are only the most resilient creatures — mussels and barnacles — stubbornly clinging to a now steep-sided and rocky shore.

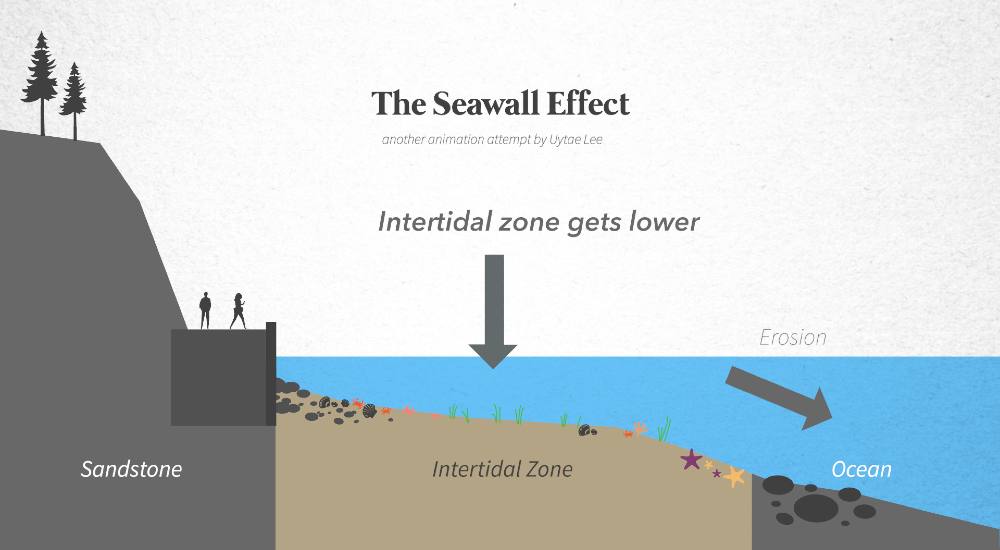

Over in Stanley Park, where wave action is greater, the nearshore habitat faced a different problem: a lack of sand. This illustration by Lee demonstrates this effect.

The seawall stops erosion of the sandstone bedrock, preventing new sand from being added into the intertidal zone — important for eelgrass, starfish and native crabs that make home in the sand. At the same time, the ocean is pulling existing sand from the intertidal zone out to sea. The result is a depleted, rocky habitat devoid of the same burrowing creatures that once called the area home.

But nature is resilient, and a quick peek under the waves still yields observations of life forms that have made their homes on the seawall. However, these underwater communities differ greatly compared to those around natural shorelines, due to differences in habitat structure, wave intensity and other physical factors.

This is why seawalls are also favourable for the spread of non-native species such as the European green crab, who are more adept at surviving in hostile, disturbed environments. This mix of habitat loss and competition with invasive species is another blow to an already at-risk starfish population suffering mass die-offs due to “sea star wasting syndrome.”

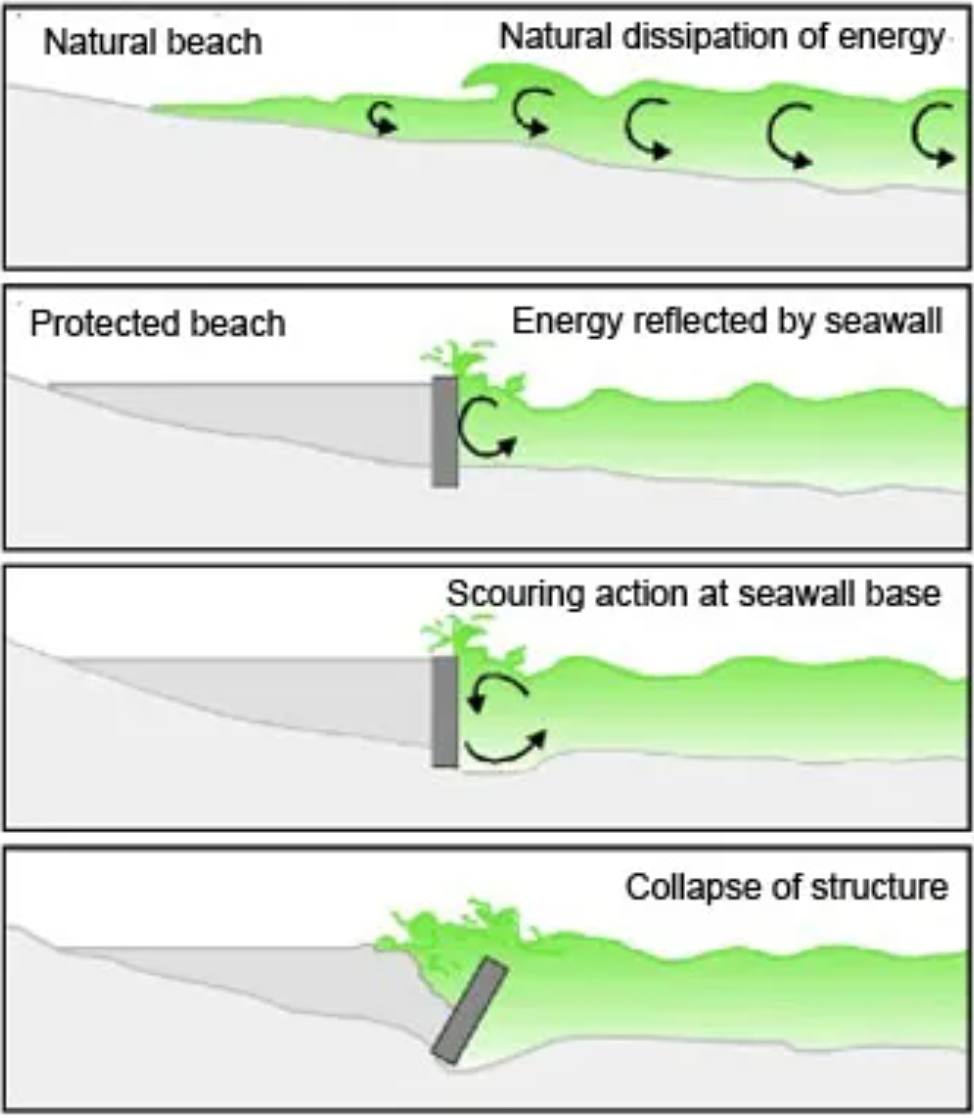

It’s not just starfish that are paying a price. We are as well. Each year, storm surges and king tides deal expensive blows to our precious waterfront path. Ironically, seawalls increase wave energy, redirecting it into the intertidal zone and causing seafloor scouring. This often results in seawall collapse. Increased turbulence also makes it harder for aquatic plants to establish and grow, leaving an already barren habitat even more desolate.

There’s also climate change. In Vancouver, it’s expected that approximately one metre of sea level rise will occur by 2100. Adaptation projects to cope with the rising waters often run into the millions of dollars.

It’s obvious that our current strategy for the seawall — patching its holes, making it taller, and hoping for the best — is unsustainable. And demolishing the thing outright is sure to draw the ire of every jogger and cyclist in town.

So where do we go from here?

Moving on

Local conservation startup Surge has some ideas. Launched in 2021, Surge wants to create Canada’s first “living breakwaters,” offshore oyster reefs with a dual function. They break up wave energy before it reaches the coast while filtering the water at the same time. Oyster reefs are less expensive to build and maintain compared to seawalls and as living pieces of infrastructure, they’re better suited to an increasingly unpredictable marine environment. These breakwaters are just one piece of a larger movement to seek nature-based solutions to deal with climate impacts.

Surge’s founders Sherry Da and Will Crolla, both local youth, shared some of their goals with me.

“We want to first and foremost complete a successful pilot stage,” says Crolla. “Achieving this means finding an available coastal engineer to help us with the technical side of the design, then working with necessary stakeholders to identify the best locations for this project.”

Da also brings up a roadblock that they have been facing: finding funding.

“Funding has definitely been a challenge,” Da tells me. “There is a lot of talk about youth leadership, engagement and capacity building, but there are not sustained systems of support to allow us to bring our ideas to fruition, especially as a young social entrepreneurship.”

The work of Surge underscores a shared desire that many youth-led movements have for immediate, on-the-ground climate action.

Crolla puts it well: “If we work together and look at better solutions instead of doing the same thing over and over, we can create more resilient communities, ecosystems, cities and societies.”

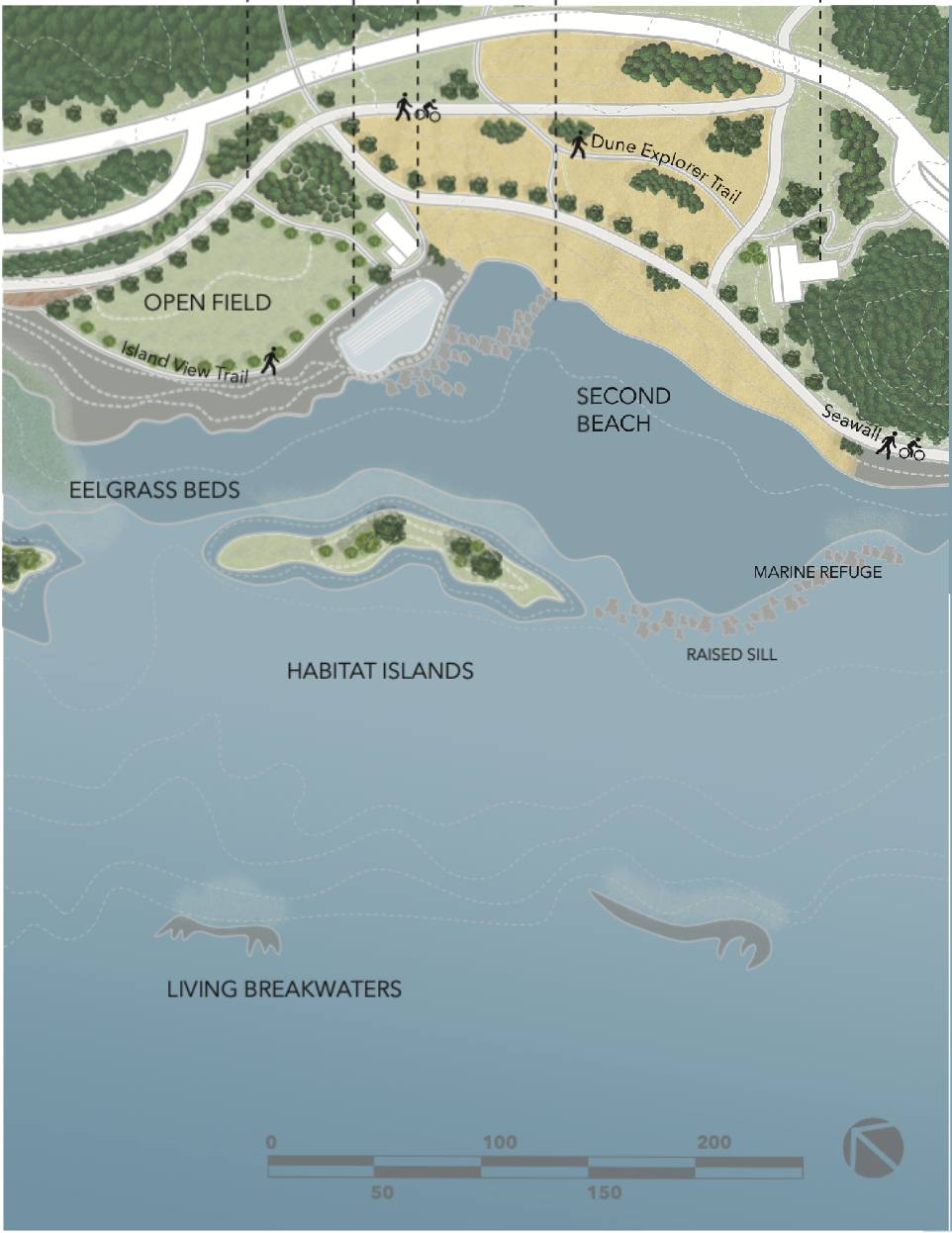

Their eventual goal is that oyster reefs can be part of a redesigned Vancouver shoreline that includes historical habitat types like eelgrass meadows and coastal salt marshes.

A better future

What does this redesigned coast look like? Landscape architect Ali Canning’s thesis, titled "Walled Off," imagines new configurations for the Stanley Park seawall that are more resilient to storms by restoring habitats such as tidal flats, natural rocky shores and sand dunes.

Canning’s designs also acknowledge the social, economic and cultural benefits that the seawall provides to residents and visitors of Vancouver. Her designs maintain public access to the water through a network of boardwalks and seaside paths and they encourage a more informed connection to the natural environment through the use of educational signage.

In False Creek, the City of Vancouver recently held the Sea2City Design Challenge, tasking teams of architects, planners and engineers to come up with designs that restore historical biodiversity and build flood resiliency. Preliminary designs include softening shorelines and building elevated walkways above restored mudflats and eelgrass meadows.

The Squamish Streamkeepers are also working in the False Creek area, building and maintaining artificial herring spawning substrate at Fisherman’s Wharf with the goal of bringing back a once-abundant herring population that has suffered greatly due to the loss of their natural spawning habitat.

There’s also the False Creek Friends society, who alongside the Hakai Institute, conducted the first-ever “BioBlitz” of False Creek in September. The goal of the BioBlitz was “building a library of life” and raising awareness that no, False Creek is not dead.

Researchers, planners and local communities are slowly realizing that greening the urban environment is often the best way to adapt our cities to the ongoing climate emergency. For too long, environmental action has been framed as sacrifices we must make to protect the Earth. Give up meat. Buy less. Take shorter showers. And while reducing our consumption is important, restoring the complex, vibrant habitats that our cities were built on can create a more livable, resilient city for residents too. ![]()

Read more: Municipal Politics, Environment, Urban Planning

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: