As the saying goes: “extinction is forever.”

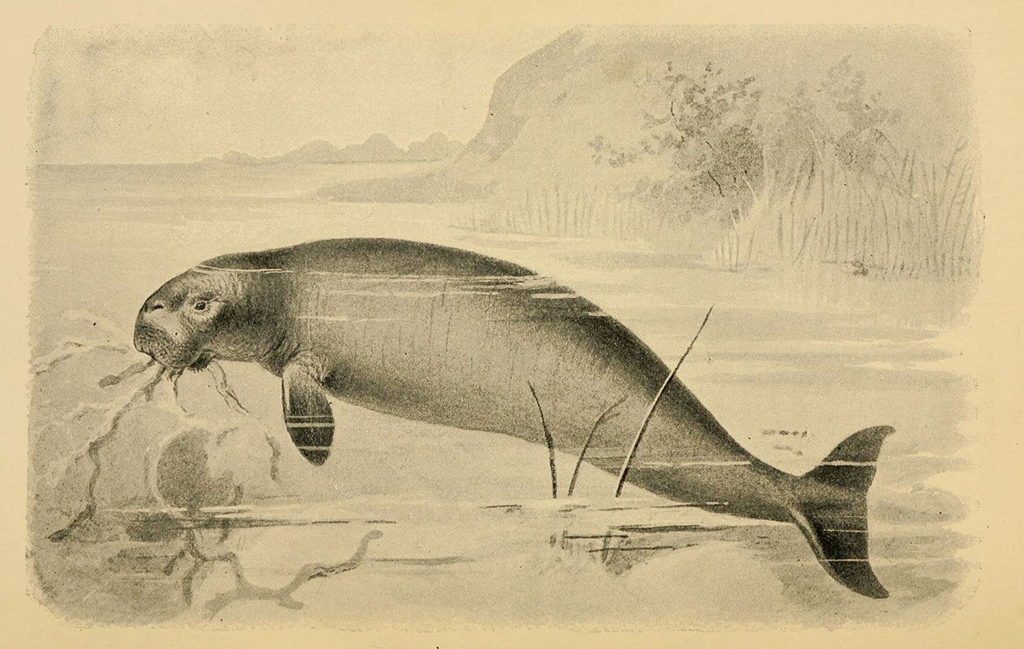

The list of extinct animals, like Steller’s sea cow, the Tasmanian wolf and the dodo, is depressing. And despite various efforts, extinction seems final.

But when does extinction start? That would seem like an easy question to answer. In the dry prose of the International Union for Conservation of Nature, extinction has occurred when “there is no reasonable doubt that the last individual of a species has died.”

And as we know from watching courtroom dramas, the concept of “no reasonable doubt” is a high bar, meant to protect the innocent in society. In conservation, it is to guard against crying wolf.

In the 1980s, it was suggested that an extinction should be declared if a species was not observed for 50 years. That seems like a long time, but it wasn’t long enough. Many species have been rediscovered decades or even centuries after their last observation.

For example, the black-browed babbler was recently recorded in the jungles of Borneo for the first time in 170 years!

It’s been almost 200 years since the last documented record of the Black-browed Babbler. This species was thought to be lost until last year, when community members in Borneo found it by chance! Conservation efforts are now underway to protect this bird. https://t.co/1WXlNlU6pg pic.twitter.com/s4qcRsYx9x

— American Bird Conservancy (@ABCbirds) February 25, 2021

And indeed, extinction need not technically be forever: some rediscovered species had been formally declared extinct. These species are referred to as Lazarus species — for instance, the Miles’ robber frog was brought back from the dead after it was located in a Honduran cloud forest in 2008.

Incorrectly declaring a species extinct can have serious consequences. Potentially urgent conservation actions for the species in question stop, and in some cases, those conservation actions can help protect entire ecosystems.

Perhaps more importantly, crying wolf undermines the credibility of extinction as a label.

Beyond reasonable doubt is a conservative position, but it leaves us in a bit of a pickle. With our colleague, Andrew Fairbairn, we recently documented that surprisingly many species have not been seen in over 50 years, and remain in a sort of limbo between extant (species that are currently living) and extinct.

Putting species in limbo is not helpful. A 2019 report by the United Nations suggested that a million species are threatened with extinction (roughly 12 per cent of all species). The actual number of species that have been declared extinct by the IUCN seems, on the face of it, much less dramatic: only 85 mammals or less than two per cent of that group, for instance.

Such a mismatch can, to put it mildly, sow confusion. And because more and more species are predicted to become extinct, discrepancies between the number of “going extinct” and the number of “gone extinct” species may become more of a problem.

In our study, we found that 562 terrestrial vertebrates — mammals, birds, amphibians and reptiles — are currently stuck in lost species limbo, almost twice as many as the number declared extinct.

None of these have been declared extinct, but none have been reliably observed for at least 50 years. The famous ivory-billed woodpecker was last seen in 1944, although purported sightings continue to this day. And the last confirmed sighting of a Canadian species, the northern curlew, was in 1963.

While most of these lost species are (or were) found in the tropics, they also hail from the United States, China, Australia and Canada, and include everything from tiny shrews and salamanders to dolphins and wild cattle.

So what should be done about the confusing problem of lost species? Clearly, the answer is to go looking for them.

That is, of course, easier said than done. Many lost species live in remote ecosystems that are difficult to reach, like inaccessible rainforests or vast tundras. There are plenty of skilled field scientists who would love nothing more than to spend their time in under-studied ecosystems searching for lost animals, but funding to support such fieldwork is becoming increasingly scarce.

Securing funding sources to support searches for lost species is therefore important. This could perhaps be helped by better awareness of and management of lost species as a group. While 50 years is an arbitrary measure, it might help focus attention by defining a clear list of candidate species.

We envision a scorecard of lost species, updated as time passes and species go on and come off when rediscovered or declared extinct.

We end with the full and depressing formal definition of extinct: “a taxon is presumed Extinct when exhaustive surveys in known and/or expected habitat, at appropriate times (diurnal, seasonal, annual), throughout its historic range have failed to record an individual.”

We believe many lost species are not extinct, and so will be rediscovered. Each rediscovery will be cause for minor celebration and, we would hope, renewed attention and interest. But we really need to know, one way or the other.

Tom Martin, a conservation scientist with the Wild Planet Trust, and Gareth Bennett, an undergraduate student in biological sciences at Simon Fraser University, co-authored this article. ![]()

Read more: Science + Tech, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: