- A Long Way Gone: Memoir of a Boy Soldier

- Douglas & McIntyre (2007)

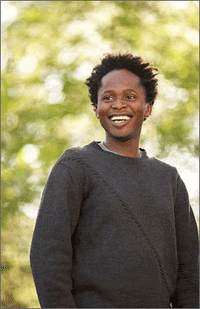

Meeting Ishmael Beah is a disorienting experience. Here is someone who once competed with other child soldiers to see who could slash the throats of captured prisoners most quickly. Beah won. It's one of many chilling scenes in his book, A Long Way Gone: Memoir of a Boy Soldier.

And yet here was Beah when I met him, courteously holding the door of an elevator for me to enter. That was in March, during the Vancouver leg of his book tour. In our conversation, Beah proved to be charming, eloquent and humorous. He was also a publicist's dream: dressed in a hip maroon shirt and blue jeans, with Gap ad good looks and a smile that would make a room full of dental hygienists swoon.

It has been a remarkable year for Beah. His book rides high on bestseller lists. He has graced American talk shows and starred in Bling'd, a VH1 documentary that takes American rappers to the diamond mines of Sierra Leone. Even Jon Stewart has paid tribute.

'Second life'

All these successes belong to what Beah, now 26, calls his "second life." But they would not have happened were it not for the cruelty of his first life in Sierra Leone. "I was in college when I started to write a book about my past," said Beah. "I thought the writing would help me understand certain things and come to terms with certain things. For lack of better word, that it would be 'therapeutic.'"

But before I tell you more about Beah, I want give you two reasons why you should read his book right now: the Omar Khadr and Charles Taylor trials.

On Monday last week, two United States military judges decided to drop war crimes charges against Khadr, who has been held in the Guantanamo Bay prison for five years. Khadr was accused of killing an American medic during a battle with U.S. forces in Afghanistan in 2002. The judges dismissed the case because Khadr had been classified as an "enemy combatant," and military commissions like the one at Guantanamo Bay can only try "unlawful enemy combatants." (This is not a trivial technicality: the military commissions were created to circumvent the United States' obligations under the Geneva Convention, which would normally apply to enemy combatants. See here, for example.) Prosecutors will likely appeal the ruling, but no tribunal yet exists to hear that appeal. Khadr will remain at Guantanamo Bay indefinitely.

Child adults

But whether Khadr was a lawful or unlawful combatant, one thing is certain: he was 15 years old when American soldiers captured him. Should a child soldier be tried for war crimes?

U.S. Army Sergeant First Class Layne Morris argues that Khadr should be treated as an adult. For proof, Morris described Khadr's behaviour in the battle in which Khadr allegedly killed an American soldier. (Morris was injured in the same clash.) Trapped in a compound besieged by American troops, Khadr chose not to escape with a group of women. The Americans then bombed the compound, killing most of Khadr's companions. When American ground forces entered, the injured Khadr threw a grenade at them. "Anyone who thinks those are the actions of a child, I can't even take them seriously," Morris told CBC's The Current on Tuesday.

Had he read Ishmael Beah's book, Morris would know that this is exactly how a child soldier would act. They are fierce fighters and suicidally loyal to superiors -- that is why child soldiers are used. Moreover, international legal convention, psychological research, and common sense all tell us that most youths are easily manipulated and therefore not entirely responsible for their actions. Indeed, David Crane, the former chief prosecutor at the Special Court for Sierra Leone, said that he would not prosecute child soldiers because they were "as much victims as the people they raped, maimed and mutilated."

Ishmael Beah committed much more heinous acts than those attributed to Omar Khadr. Now Beah is on talk shows and Khadr remains in indefinite incarceration. Were their situations really different? Or is it just that Beah killed Sierra Leonean civilians, while Khadr allegedly killed a single American soldier?

Fascinatingly repugnant

Now here is the second reason why this book is timely: Charles Taylor is on trial in The Hague. The former president of Liberia is accused of fomenting a civil war in Sierra Leone that caused over 50,000 deaths. The conflict, fuelled in part by proceeds from "blood diamonds," became notorious for roving militias that torched villages, kidnapped and raped women and amputated limbs. Many of the perpetrators were children, and one of the charges against Taylor is that he conscripted child soldiers.

The trial will get plenty of attention. Not only is Taylor a former African leader, he is also a fascinatingly repugnant individual. Born in Liberia, he studied in the United States, escaped from a prison in Massachusetts, trained in Libyan revolutionary camps under Muammar Gaddafi, and led a vicious rebel army in Liberia. Liberian civilians became so terrified of Taylor's forces that they elected him president in 1997 in the hope that this would end the civil war. Charles Taylor's winning election slogan was: "He killed my ma, he killed my pa, I vote for him."

Ishmael Beah, when we spoke in March, said that he was looking forward to Taylor's trial. "It shows people that no one is above law, not even a former president."

But Beah added that the trial should have taken place in Sierra Leone, instead of being moved to The Netherlands out of fear of attack by Taylor sympathizers. "Sierra Leoneans should be able to see justice done in their own country," said Beah. "Removing him to The Hague shows that in Sierra Leone, all you have to do is threaten violence and the judicial system will cower."

Lost boys

With the trials of Omar Khadr and Charles Taylor now in the news, A Long Way Gone is a timely book. But it is also a compelling work of literature, one that will be read long after the headlines change.

The story begins with Beah, then 12, on his way to a nearby village to perform in a rap and dance group with his older brother. When rebels attack, the boys are separated. Beah begins a picaresque journey across the war torn countryside, looking for family members. He often wanders with other lost boys, all of them hungry, ill, desperate, chased by wild boar and by villagers who think they are rebel spies.

Beah's descriptions of these travels, seen through the eyes of a traumatized child, are tinged with magic realism. Here is Beah fleeing with a group of boys from a rebel attack:

I was behind Alhaji, who parted the bushes like a diver heading to the surface for air. Some of the buses slapped me, but I didn't stop. The gunshots grew louder behind us. We ran for hours, deeper into the forest. The path ended, but we kept running until the sky swallowed the sun and gave birth to the moon. The bullets continued to fly behind us, but now their redness could be seen as they pierced through the bushes. The moon disappeared and took the stars with it, making the sky weep. Its tears saved us from the red bullets.

We spent the night breathing heavily under bushes soaked with rain.

At last, Beah and the other children find themselves in a village protected by a government-aligned militia. The commander gives the boys a choice: join his forces and help fight the rebels, or continue to wander the countryside in fear of the next attack. Soon the boys are carrying AK-47s and sneaking through the jungle toward their first battle.

'Rambo' revived

In the months that follow, the new recruits are kept high on drugs, whether engaged in combat or watching war movies at base camp. Killing soon becomes a routine, and often a game. As the boys advance on one village, Beah's friend decides to use a tactic he learned from the Rambo movies. He smears himself in dirt and crawls toward the huts. Beah watches as his friend sneaks behind a man, covers his mouth and slices his throat open. (I felt like photocopying this page in the book and mailing it to Sylvester Stallone with the words: "Sly, you must be proud that so many kids look up to you.")

Then, one day, some men from UNICEF arrive and take the youngest child soldiers away to be decommissioned and rehabilitated. Beah is one of them. He was 15 at the time -- the same age as Omar Khadr was when captured. But while Khadr was put in a military prison, Beah was taken to a rehabilitation centre called Benin Home.

The staff at Benin Home are the real heroes of Beah's memoir. In the first weeks the former child soldiers suffer excruciating withdrawal symptoms, and they self-medicate with violence, attacking each other and the centre's staff.

When Beah returned to Sierra Leone last year, he visited Benin Home and thanked the counsellors. "Those people were amazingly strong," Beah told me. "We would do all kinds of things to them and they would come back and help us. Their only goal was to show us that we were trusted and that we could get hold of ourselves. They rekindled our humanity."

Ultimately, Beah's story gives us reason to be fearful and optimistic about children who are dragged into war.

"You know, it really is not difficult to turn a child into a killer," said Beah. "It requires serious coercion and extreme violence, which in the context of war can happen easily.

"But to heal a child requires genuine care and compassion and a real, long-term commitment. It is extremely difficult. But it can be done."