[Editor's note: Read the previous story in this series here. You can also click here to download a copy of the entire series in PDF.]

One of Canada's most affordable green homes stands not in the swaggering "Green Capital" of Vancouver, but in B.C.'s actual capital, Victoria.

Designer Keith Dewey built his own home out of eight end-of-life shipping containers. In so doing, he saved five years worth of electricity and spared about 70 trees -- all while cutting the cost of his new home by roughly 28 per cent.

"Initially, everyone's perception is that steel containers must be cold, cramped and uninviting," Dewey said of the reaction to his custom home, pictured in the slide show above. "That perception dissipates as soon as they step inside."

Dewey, who will talk about his home this Thursday night at the Quick Homes Superchallenge, added, "I was trying to create a green house that was well within the realm of feasibility for an average builder. So I didn't get too extreme with anything."

Victoria inspector supported the plan

"The idea of using shipping containers came to my attention back in 2000, when I saw a magazine cover about a project called Future Shack, which was developed in Australia," Dewey told The Tyee. "That really captivated my imagination."

The designer toyed with the concept over the next few years, and, "when the opportunity arose for us to design our own house, it was a natural development of the ideas that I'd conceptualized."

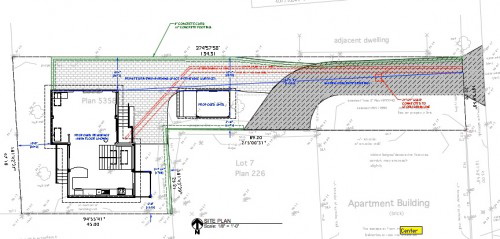

Dewey built the home he calls Zigloo Domestique in 2006. The 1,920-square-foot home is nestled into a small L-shaped lot in the Fernwood neighbourhood. The open-plan home rests on a typical residential foundation.

The City of Victoria's building inspector required Dewey to employ a structural engineer and a building envelope specialist, but otherwise treated the project like any other single-family residential home.

"We found ways to harmonize what is already known about the residential building industry with things that are already known about the shipping container industry," Dewey said of his approach.

For example, he framed two-inch interior walls at two-foot centres, and sprayed foam insulation into the void.

"It ended up being closer to four inches of foam, because there's a little bit of an air gap between the two-by-two wall and the steel, and then there's the corrugated nature of the steel wall itself," Dewey said. "We got R-28, which is well above the minimum requirement."

He topped the house with a conventional wood-framed roof, and dry walled much of the interior -- leaving strategically placed sections of corrugated steel as accents.

The house carries a traditional mortgage.

"I was able to convince the mortgage and insurance companies of the fact that this is a steel frame building, which just happens to have steel cladding. Once they were able to categorize it that way, then it was not problem," he said.

'A natural resource of consumer society'

"The sustainability issue was important for me. In my mind, a sustainable concept is one that makes use of materials that have already served their purpose. So I went out looking for end-of-life containers... things that were between 12 and 26 years old," Dewey said.

"These shipping containers, of course, we've got them all over the place. In a way they've become a natural resource of consumer society: everything comes to us in this box, but we have no use for the box now," he said.

Dewey bought eight used shipping containers, each measuring 20 feet long by eight feet wide by 8.5 feet high. He paid between $2,000 and $2,400 per container.

"A lot of them had dents and dings. One even had a breach on the side,” he said. "By itemizing our inventory, I was able to use those in areas where I would be cutting out portions of the wall."

Thousands of old shipping containers like the ones Dewey bought are melted and recycled into new steel every year due to a variety of economic factors, including ocean-going insurance requirements, the high price paid for scrap metal, and North America's ongoing trade imbalance with Asia.

By reusing -- rather than recycling -- most of the steel in those eight containers, Dewey saved something in the range of 50,000 kilowatt-hours of energy. That's enough hydro to light his home from the day he moved in through sometime next year.

Dewey also saved a small forest. Though Zigloo Domestique makes extensive use of manufactured wood products such as paneling and cabinetry, it employs less raw framing timber than a wood-frame house.

"I figured that I saved 70 trees worth of wood by reusing the containers," Dewey said.

The house has a concrete floor on the main level, which was poured atop a grid of hot water lines that provide radiant heat. The hot water is supplied by an on-demand (tankless) hot water heater.

"It's a very efficiently heated house... by heating the basement and the main floor, the residual heat rises up the stairwell and flows through the remainder of the house," Dewey said.

"It's easy to cool, too. By strategically placing operable windows, we are able to get really nice summer breezes," he added.

A custom home for a spec-house price

"My idea was to design a custom home, using sustainable materials, and do it for the same price they were building spec quality houses out in the low-cost subdivisions," Dewey said.

In Victoria, spec homes run about $150 per square foot, while custom homes average about double that.

In addition to the engineer and envelope specialist, Dewey contracted professionals for all the trade work such as electrical, plumbing, drywall, painting, etc. The only cost he avoided was his own design fee.

"I didn't cash in any favours on this one. I wanted to see what the costs really were," he said.

"As it all turns out, we were able to do it for $180 per square foot," he said.

"I would easily stack this house up against any house out there for $250 per square foot or more. So I'm assuming we saved in the realm of $70 per square foot, mostly as a result of the reuse of these containers."

That works out to a 28 per cent savings, which is consistent with the 25 per cent estimate provided by Barry Naef of the Intermodal Steel Building Unit (ISBU) Association.

Dewey acknowledged that he spent an inordinate amount of time and money working out solutions to specific design problems. The building envelope, for example, required considerable attention.

"When you put two containers together, there is this inevitable quarter-inch gap. So we had to develop a library of little details that could prevent water and drainage," he said.

"I'm sure I will be able to do these things much more efficiently next time."

Public perception remains a challenge

Dewey has several new container-based construction projects in the works. He said they all face the same challenges.

Perception is the first. The most common container buildings are the thousands of workers' camps scattered across the booming Arab states, along with a small number of mining camps in remote locations.

"They look a bit like concentration camps... That does not help overcome the perception problem," he said.

"That's why I think the designer is a really important element. There are lots of engineers and fabricators who can fabricate something low cost, easy to maintain, and durable. But if it's not appealing, if it's not an attractive thing for people to walk by, then it's not going to work in an urban environment."

Unrealistic expectations about cost are the second challenge.

"Nine times out of ten people are wanting something cheaper... People call me and they say, 'Oh, it's a box, and it's cheap,'" he complained.

"There is money to be saved using shipping containers," he said, "but the cost of the house is much more than the cost of the used container."

Dewey does anticipate that once the form becomes more widely accepted, complete homes will be manufactured in low-wage regions and sold worldwide.

"We're not quite there yet, but there is the potential for these homes to become extremely affordable in pre-fab manufacturing," he said.

He designed a pre-fab workers housing complex called Modulute, which would have created 220 small, self-contained suites. Whistler approved the $3 million project a couple years before the recent Winter Games, but the American vendor contracted to prefabricate the containers was unable to secure financing during the 2008 recession.

"It was an easily stackable configure that could have been removed and reinstalled somewhere else," Dewey said. "It's a bit of a shame. It would have been a real nice spotlight project during the Games."

For the time being, he said, the container concept is catching on much more quickly in Europe. He cited Amsterdam's Keetwonen project and London's Container City developments as examples. (See yesterday's slide show for pictures of those projects.)

"I guess there's sort of a conservative mindset in North American culture," Dewey chuckled. "We say, 'I've got to see it to believe it. And I'm not going to look too hard to try to find it.'"

For a vitual tour of Zigloo Domestique, click on the slide show at the top of this page or visit Dewey's web site.

Tomorrow: Could pre-fab suites make buying a home as simple as buying a refrigerator? ![]()

Read more: Environment, Urban Planning + Architecture

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Do not:

Do: