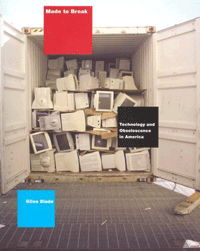

- Made to Break: Technology and Obsolescence in America

- Harvard University Press (2005)

- Bookstore Finder

Itching for a sweet new Nokia? It's probably high time. Your friends have been knocking your phone for years. Face it, you're talking into the personal-electronics equivalent of Sputnik. The screen is cracked, the battery is flagging. And no Bluetooth!?

Well hold your horses, says Giles Slade.

In Made to Break: Technology and Obsolescence in America, the Richmond, B.C.-based author explains in painful detail why cast-off cell phones -- and countless other products and electronic devices, from pocket calculators to PCs -- are quietly creating the largest toxic waste stream the world has ever known. The situation is bad, and in three years' time, he notes, it's about to get much worse.

To be clear, Made to Break is not a book about e-waste. (There are several of those out there, including Elizabeth Grossman's excellent High Tech Trash.) Rather, it is a meticulous history of planned obsolescence -- the practice of engineering or designing products in such a manner that they become either socially undesirable or non-functional after a given time period. Under the banner of "innovation." Slade argues that this technical and psychological obsolescence -- and the parallel phenomenon of disposability -- have over the course of a century become so ingrained in western consumer culture that our very economy depends on it to survive.

For many decades, trash was simply the relatively benign end-product of the endless struggle to keep up with the Joneses. But the digital age marked the start of a darker chapter in our ongoing love affair with the latest-and-greatest. Our gadgets, it seems, simply get older much faster than they used to. This gradual tightening of product life-cycles dominates the final -- and perhaps most disturbing -- section of Made to Break.

We asked Slade to give us a quick and painless upgrade.

James Glave: You portray planned obsolescence and disposability as forces of evil and waste. But are there any obsolete products that truly deserved to die?

Giles Slade: Cloth diapers. Though disposable diapers are very serious pollutants, cloth is not very effective. Disposables are just so user-friendly. In the same way that Tampax tampons made Kotex obsolete, I don't think we can go back. I am a big fan of disposable diapers.

How do obsolescence and disposability interrelate? And did the initial architects of disposability foresee the issue of waste?

Disposability was first created with paper clothing products, like paper shirt-fronts, collars and cuffs. You'd take off your shirt collar at the end of the day and stick it in the stove, and it was gone. It was only later that metal watches and Gillette razor blades started going into landfills. Once disposability was invented, then planned obsolescence could occur. We had invented mass production, and we had to feed the machine -- we had to get people to buy new stuff -- and obsolescence emerged as the answer. Waste was simply the after-phenomenon.

When did this happen; can we pinpoint when American industry first embraced obsolescence as a business practice?

When Alfred Sloan took over General Motors in 1923, he found he had to bring a really bad Chevrolet to market. It was a piece of crap. He planned to improve the car, but he had no time. So he tarted it up with some styling changes, and then undercut the price of Ford's Model T. It worked like a charm. He invented psychological obsolescence.

Which one single invention stands out in your mind as the killer app of obsolescence -- the one product that prompted or compelled us to chuck its predecessor, with grim consequences?

It hasn't happened yet but it's just about to. By 2009, the FCC [the U.S. Federal Communications Commission] will have mandated the complete change from analog to digital television. All the older TVs have cathode-ray tubes that contain maybe five to 10 pounds of lead. Television enjoys a 95 per cent market penetration in the United States, which would mean that, conservatively, there are about 300 million of them out there in living rooms and dens and basements. And they are about to be chucked. The sheer amount of toxic lead that is about to enter the waste stream is simply going to overwhelm it -- there are not enough container ships to send these obsolete televisions off to Asia where they can be broken up safely. This is a massive biohazard that is about to enter America's groundwater. And it is going to happen because electronic manufacturers lobbied the FCC to mandate digital TV. The problem for them was, there is not enough obsolescence in the television market; they are built to last five to seven years. That was too long.

Is it too late to stop this?

In the U.S., four states have enacted take-back programs similar to the regulations in Europe, where electronics manufacturers have to pay to collect and disassemble TV cathode-ray tubes. About 19 others are considering similar legislation. There are four similar bills in the Congress and the Senate. But there is no political will to do this because it is an invisible issue.

Your book seems to give Apple a reasonably positive treatment. But what about the allegations that the iPod is engineered to die after 18 months or so?

Steve Jobs came out recently and pretty much admitted that the iPod should be thought of as a disposable product. It is a slick, sleek thing, and you would never consider that it comes from a fundamentally dirty industry. In fact, the amount of toxins that go into an iPod is enormous. There are more than 68 million of these things out there, and they are full of cadmium, beryllium and lead. And Apple has deliberately created them so they only last a year. The company has a voluntary take-back program, but how many people use it? They won't say. I am hugely personally disappointed in Steve Jobs. He turned into Darth Vader.

But the real Darth Vader in your book isn't Steve Jobs, it's the mobile phone, which you explain is now on roughly a 12-month product life-cycle. You have given all the cellphone holdouts a whole new set of reasons to feel smug.

I do own a cell phone, a Motorola flip-phone. It is a wonderful device, but I plan to hang on to it for a long time. Cellphones are now deliberately underbuilt: They are so closely linked to style and fashion, that manufacturers realize people want to trade them in after a year or so, and so they make them to break. Some manufacturers are being smarter about it. Ericsson has designed a prototype cellphone that uses a process called "metal memory" to disassemble itself when you are finished with it. When it receives a signal from its owner, it will take itself apart into distinct recyclable components. Motorola makes a phone that contains a sunflower seed. Obviously nobody is going to plant the phone in the garden, but it illustrates a point that it should be disposed of properly.

Made to Break details a fascinating and obscure chapter in the Cold War, in which the West intentionally leaked faulty technology to the Soviets -- chips and software that, once installed, failed with spectacular results. What does this have to do with obsolescence?

The Soviets had this policy of stealing tech from other people -- they had a whole sector employing some 20,000 people who were dedicated to stealing secrets from the West. But the Americans learned where the agents were operating. The Soviets tried to buy pipeline-control software from an American firm, but couldn't, so they infiltrated a Canadian firm -- nobody will tell me its name -- and stole the software. But with some help from U.S. intelligence, this Canadian company had intentionally leaked them tampered software; it operated very well for 18 months, and then, in 1983, it collapsed. It directed volumes of gas into pipelines that could not withstand the pressure. Sometime that year, U.S. satellites picked up a tremendous blast in Siberia. It was a three-kiloton explosion, the most monumental non-nuclear explosion and fire ever seen from space. This episode is significant because it revealed how planned obsolescence -- the technological Trojan Horse -- had become such a cultural principal in the United States that it was elevated to the level of geopolitics, and in that arena it worked very well.

Your critics will say that the flipside of obsolescence is innovation. Isn't it a pretty fatalistic view that innovation is fundamentally making our lives worse instead of better?

In researching this book, I came to respect technology a lot more and to see it as another field of human endeavour like the arts. It is, in fact, heroic. I am not down on innovation, I'm not down on tool use. I am down on the careless and casual consumption of IT products for silly pleasures. This is a period in our existence that better end pretty soon, because we are going to poison our kids with it -- all for toys. We are at a similar point in the history of technology as what happened with the sexual revolution when HIV came along. All of a sudden, you had to be very careful and conscious. We have to practice safe and conscious information-technology consumption, so we don't junk an iPod every year, so we don't throw all this poison into the water or send it off to Asia where it can be processed. We are at a critical point where we either have to act now, or act when the crisis occurs. It is admittedly a very dark view, but it is also very mainstream.

Are we to blame, or is industry?

A lot of it is simply greedy IT manufacturers. In Europe, they have passed laws that make sure that electronic manufacturers can't use toxic substances in devices when they manufacture new things. They have to pay to back the old ones and disassemble them and reuse them.

Governments and companies would do the same thing here if we demanded it. But we don't. Why not?

We have become creatures of conscious self-display. You are what you drive or wear. You are the model Blackberry that you use. Life used to be better when things weren't that reductive. There is a sense of entitlement that we suffer under that doesn't exist in other cultures -- one that really makes us weaker. I am the last person who wants to give up my car, and I don't want my kids to go without food. But we are doing all this on credit, and I don't think it is going to last.

Your conclusion calls for a new emphasis on education and techno-literacy. Where is this awareness going to come from?

The world is becoming so much more complex that intelligent people are casting around for areas of knowledge and experience that they've put off informing themselves about for too long. There's almost a glut of books, articles and programs about global warming and the environment. Young people are concerned about the environment, hip to new tech, and they see that they need to know more about the connections between the two. After all, this generation's cultural hero is an iPod. The world is becoming an enormously complex place in many different ways, and anyone who wants to participate is watching, reading, scanning, and listening, trying to find pieces of the picture that will help them cope, become successful, make their way. Technology and the environment are now primed to become mainstream issues -- and election issues. So things are looking up.

James Glave ([email protected]) is a writer living on Bowen Island, B.C. He blogs about climate change and sustainability issues at The Big Melt. ![]()