"A call to arms may be wrong. We may not even know who the enemy is. And maybe the enemy is us." -- Matt Simmons

After criticizing the reckless conduct of BP in the Gulf of Mexico most of the summer, 67-year-old Matt Simmons eased into his hot tub at his home in North Haven, Maine on Aug. 8. For a short while the famous oil analyst might have pondered his grandiose plans for the world's largest $25-billion offshore wind farm. But Simmons then suffered a heart attack and drowned.

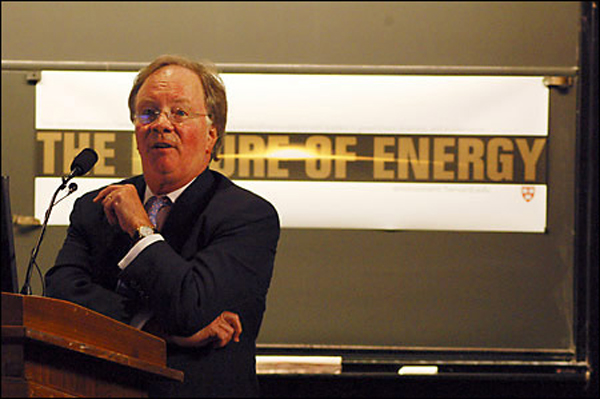

The New York Times duly observed the passing of "the noted energy banker" while Forbes called him "the crazy uncle of the oil patch." And that he was. Gadfly. Visionary. Contrarian. Educator. "Crude Cassandra." Conservative. Together with millions of Americans and Europeans, I dearly miss the life-long Republican and let me tell you why.

Not too many people in the oil patch speak honestly about the world's most powerful industry, but Simmons did. He didn’t let the money, bullshit or arrogance cloud his judgment. Or his basic reading of geology for that matter.

A Bush in his hand

Simmons, who convinced George W. Bush that America was indeed addicted to oil (and that was no easy feat), often spoke about the realities of depletion. He knew that the multinationals and state oil companies had netted most of the world's big petroleum fish 50 years ago and that the world's major oil fields, like the world's major fisheries, were all in a state of depletion. With the big, easy fish gone, industry was now chasing "junk crude" in the tar sands or the ugly, difficult and tough stuff at the bottom of the barrel. While sanity might renew ocean fishing, the depletion of cheap oil era was irreversible.

"What that means," he once said, "in the starkest possible terms, is that we are no longer going to be able to grow. It's like a human being who passes a certain age in life. Getting older does not mean the same thing as death. It means progressively diminishing capacity, a rapid decline, followed by a long tail."

Just what we need

Simmons, of course, recognized that petroleum was the industrial oxygen that built modern civilization over the last 100 years. No economy can grow its GDP without burning more oil. As a consequence he warned that the end of cheap oil would challenge every aspect of our economy as well as 100 years of lazy, oil-induced thinking. He also didn't believe that unconventional bottom-of-the-barrel replacements such as bitumen or shale gas could offset the decline.

In short, Simmons was to the oil industry what Nassim Nicholas Taleb is to economists and bankers: a breath of fresh air.

Although Canada calls itself "an energy superpower," the country's illiterate media pretty much ignored Simmons's death. And that's a huge omission.

David Hughes, a resident of Cortes Island and one the country's foremost energy analysts, says that Simmons contributions to North American life were incalculably patriotic.

"Matthew Simmons had rock star status among the peak oil crowd and it was justified," adds Hughes. "He was a straight shooter. He based everything on his analysis of the data. He woke people up. And he had a pile of integrity."

A must-stop for serious journalists

As a long time energy and business journalist I depended on Simmons a lot. He was my compass. Every week I'd visit the website of Simmons & Company, one of the world's top energy bankers in Houston, and I read over one of banker's latest presentations. They had titles like "Energy Markets in Chaos"; "Has Twilight in Energy Desert Begun!" or "What Kangaroo Court Created Our Oil and Gas Markets?"

It was like going to AIG's website and finding an honest account of unscrupulous banking practices and toxic derivatives. It was incongruous, surprising and refreshing. Simmons usually ended his detailed talks on the nature of depletion with a pithy comment such as "peaking of hydrocarbon supply is the 21st century's highest risk."

Unfortunately, you can't find his presentations at Simmons & Company anymore. After some hyperbolic comments in Forbes about BP's character (some of Simmons's criticisms were off character and over the top), he unceremoniously left the company that he founded. But it was no big deal. He had already set up the Ocean Energy Institute, and that's where his economic presentations now rest.

Seeing beneath the oily surface

Over the last decade I often wondered how the head of one of the world's most important energy banks could become a proponent of wind power, a blazing energy critic and an advocate for local food production. But the volatility and geology of oil pretty much made Simmons the man he was.

Oil's crazy uncle began life as the son of a Utah financier. Simmons frequently described himself as an investment banker who accidentally ended up spending 30 years engaged in energy-related investment banking. "Even after I graduated from Harvard Business School, I still considered energy simply as something you put into a gasoline tank."

During the oil crunch of the 1970s, he established Simmons & Company in Houston to specialize on investments in oil service and petroleum equipment. He even helped fund the offshore drilling boom in the Gulf as cheap oil supplies depleted on land. He had clients like Halliburton and Kerr McGee. In the process he learned much about 3D seismic and deep sea drilling and the profound limits of technology when it comes to energy production. As he told a Swedish crowd in 2002: "All this technology did was create the ability to drain fields faster and create far higher decline rates once new fields peaked."

In the 1990s Simmons annoyed many members of the oil patch by questioning conventional group think in the industry. When energy gurus predicted oil demand would not grow beyond 60 million barrels a day, Simmons warned that demand was growing too rapidly as it crossed 70 million barrels by 1995. When the gurus said that oil supplies would endlessly surge, Simmons documented the steady depletion of oil fields in the North Sea and Middle East.

Realizing all was not well in the energy world in 2002, Simmons reread The Club of Rome's report The Limits To Growth. Since its publication in 1972 traditional economists had trashed the report as a "doomsday book." But in his revisit Simmons found a sober account of how exponential growth and unbridled energy consumption would lead to constraints or a decline in industrial activity by 2050.

"In hindsight," he said, "The Club of Rome turned out to be right. We simply wasted 30 important years by ignoring this work."

Peak oil's vise grip equation

The following year Simmons took a look at the world's giant oilfields and found more troubling limits. Just 14 of the world's largest oilfields (more than 100,000 barrels a day) accounted for more than 20 per cent of global supply. Moreover the majority were more than 50 years old and there was little or no transparency about their decline rates.

Simmons didn't think ignorance about decline rates in the world's major energy account was terribly smart. "Until there is far better transparency on the world's giant oilfield production data and decline rates, the world can only guess at its future oil supply."

That lack of transparency got Simmons crunching numbers on oil supplies in Saudi Arabia. Energy analysts and Saudi spin-doctors said the country had fabulous reserves and could easily boost production from 9.5 million to 11 million barrels a day. But after reading through some 200 scientific papers published by the Society of Petroleum Engineers, Simmons concluded that Saudi's 200-billion reserve claim was "an illusion." Most of the country's oil came from five aging fields that required constant flooding with salt water to maintain production. He thought that Saudi Arabia was not only over producing its key fields but had probably peaked.

The Saudis hated the book, as much Alberta's Tories dislike Greenpeace. But Sadad al Husseini, a retired Saudi Aramco executive, thought Simmons got it mostly right: "Those who criticized his conclusions missed the global issues he was addressing: maturing oil resources, an over-extended industry, runaway energy demand, and the absence of a 'Plan B.'"

A vision of social justice

Unlike most analysts Simmons didn't shy away from talking about energy inequities. In a Beijing presentation in 2007 he told the Chinese that 565 million people in the U.S.A., Russia and Japan consume the equivalent of 44 barrels of oil a year while 3 billion folks in China, Brazil, Nigeria and India got by on 5.6 barrels. Simmons didn't think this sort of inequality was a recipe for global stability.

Simmons also gave the Chinese some straight advice. Lead the way in energy-efficient transportation and efficient shipping. Invest in renewables and hybrid cars. "China can cope better with oil peaking better than U.S.A. or Europe where infrastructure is too deeply embedded to make urgently needed changes." He also thought China could lead the world in creating a less energy- and oil-intensive economy.

Wise about water

Simmons understood the ugly marriage of energy and water, too. He understood that it takes energy to pump and treat water and that it takes extreme amounts of water to make energy. For example it takes three gallons of water to make one gallon of motor gasoline. Simmons also estimated that industry consumed 72 billion gallons of water in Texas's Barnett shale just to frack 10,000 gas wells over a three-and-a-half year period. Water consumption in the tar sands also horrified him.

Although no one has yet quantified how much water is needed to consume 85 million barrels of oil a day in the globe, Simmons reckoned it would be an offensive number. "Energy's water usage has been free and this wasteful practice has to stop."

In 2007 I interviewed Simmons about the tar sands for Canadian Business magazine. He was gracious and blunt. "If I were a Canadian, I'd make it illegal to use precious natural gas and potable freshwater to turn gold into lead in the tar sands."

His recommendations for policy makers were equally stark: go slow, charge for water, cap tar sands production and "find some other way to produce this atrocious resource other than using scarce natural gas... to get addicted to the tar sands doesn't make any sense to me." (According to Cambridge Energy Research Associates the tar sands annually consumes 20 per cent of Canada's natural gas demand.)

Limits to renewables

Unlike most greens Simmons didn't think renewables could be scaled up fast enough to create some kind of golden energy age. He thought an industrial wind farm looked as ugly as a refinery and cost an enormous amount of energy that only returned a small intermittent supply. Solar held promise, but he really liked the idea of using algae as a biofuel. In the end he invested in offshore wind with the idea of producing electricity to desalinate water to create ammonia to run cars. The desperate scale of the project aptly illustrates the desperate state of the challenge if not the limits of green technology.

Simmons, a hopeful man with five daughters, always talked about solutions. He felt that governments needed to keep the price of oil high in order to spur an energy transition and conserve a precious resource. He recognized that North Americans would have to consume less; lose weight and give up many of their oil-based energy slaves. Transportation by rail and boat made more energy sense than trucks, he said. Growing food locally was a must. He also called an economic globalization model based on cheap oil deeply "flawed."

C. S. Lewis, the Christian philosopher, once warned that people who sought comfort as opposed to the truth would only find soft soap, wishful thinking, "and in the end, despair."

I'll miss Simmons because he didn't peddle soap, eschewed wishful thinking and always looked for the truth. He knew there was no comfort without it. Even in the oil patch. ![]()

Read more: Energy, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: