[Editor's note: This is the third article in an in-depth Tyee Solutions Society series, "BC's Quest for Carbon Neutrality: Reports from Canada's Climate Policy Frontier." To meet the lead reporters on this project, see the accompanying profile today on The Tyee.]

When governments come to do battle with climate change, truly decisive action courts political suicide. Consider the challenge of putting a price on carbon -- arguably our most effective policy tool in averting global climate disaster. In July, Australian Prime Minister Julia Gillard unveiled a national carbon tax on that country's 500 worst polluters, after her predecessor was turfed from office when his own carbon pricing scheme withered on the vine. Gillard has been bloodied by an ongoing revolt led by the coal industry, and faces an uphill battle to win re-election in 2013.

Former federal Liberal leader Stephan Dion's political life ended when his partisan rivals, including the late Jack Layton, savaged his complex "Green Shift" carbon tax. Most Canadians didn't get it; even more didn't trust it. The "Green Shaft," as it became known, now serves only to deter any other North American politician brave enough to seriously address the issue.

Such cautionary tales make British Columbia's carbon pricing experiment all the more remarkable (see sidebar for the elements). There are a dozen or so carbon taxes in the world today (a chart laying all of them out can be found on page 16 of this report). Of all those levies, enacted by a patchwork of nations, provinces and even municipalities (Boulder, Colo., has one), B.C.'s tax has been widely hailed as a model of environmental and economic design.

We Have a Winner: British Columbia's Carbon Tax Woos Sceptics, gushed one headline in the Economist in July, as did a similarly glowing feature earlier this year in the New York Times, which suggested a B.C.-styled carbon tax could solve America's debt woes.

Yet in British Columbia today many remain less than enthused. Social advocates say the poor are being squeezed too hard by the tax, while an unfair chunk of the revenue is being given back to corporations. Environmentalists warn that the tax, which rose to $25/tonne on July 1, is too slight to change our bad energy habits. Meanwhile business leaders insist our small, resource-based economy shouldn't "dance alone" while global competitors continue to pollute unhindered.

Already one potential future premier, John Cummins of the upstart BC Conservatives, is proposing to kill the carbon tax, apparently believing the public mood has changed since then-NDP leader Carole James campaigned in 2008 on a promise to "axe the tax" -- and handed the BC Liberals a third straight majority.

But with the future of B.C.'s carbon tax experiment uncertain, and the next provincial election looming in May 2013, now may be the time for a little sober reflection: What has the B.C. carbon tax really achieved so far? What can we expect to see if we stick with the tax? And how might it need to change?

Good news for a change

One who calls our carbon tax a good-news story, is Stewart Elgie, a University of Ottawa law and economics professor and chair of the green economy think-tank Sustainable Prosperity.

Elgie says B.C.'s gasoline consumption has dropped by three per cent compared to the rest of Canada since the introduction of the tax, an effect that cannot be attributed to the post-2008 recession. He also points out that B.C.'s GDP has grown slightly in the three years since the tax appeared -- indicating at a bare minimum that the carbon tax hasn't hurt the economy. That, says Elgie, is because B.C.'s tax on fossil fuels was designed from the start to go as unnoticed as possible by being "revenue neutral" -- most of the money it collects from taxpayers is given back in the form of lower income and corporate taxes.

And while the carbon tax might not have won the last election for the Liberals, it didn't lose it for them either. (Politicians both inside and outside B.C. take note -- recent polling for the Pembina Institute shows that public support for the carbon tax remains strong; strong for a tax, at least.)

"B.C. is now the lowest per-capita gasoline user in Canada, and also has the lowest income tax rates in Canada," says Elgie. "That is in large part because of the carbon tax shift."

In 2008, B.C. emitted 68.7 million tonnes (Mt) of greenhouse gas emissions, measured in carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e). In all of 2009, total greenhouse gas emissions in British Columbia were down slightly to 66.9 megatonnes CO2e, according to the provincial government. Updated stats for 2010 will not be published until 2012.

How have other carbon taxes worked out?

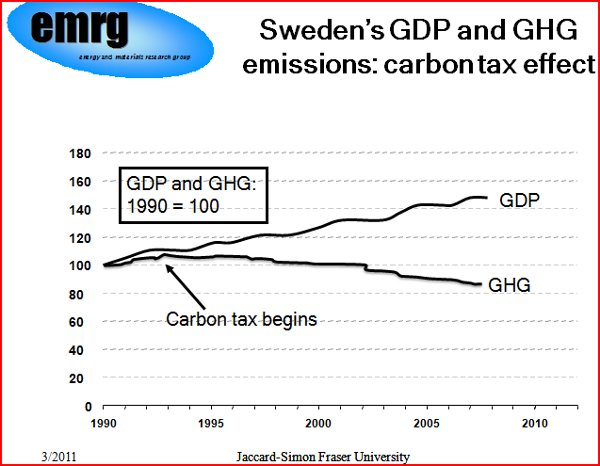

It's still early days for the B.C. tax. What can we expect in the years to come? It helps to look at Sweden, where a carbon tax has been in place for 20 years.

In 1991, Sweden imposed a carbon tax of just over $50/tonne of CO2. By December of 2008, greenhouse emissions had dropped by more than 40 per cent from levels of the mid-1970s -- well below its Kyoto commitments -- as Swedes embraced renewable energy from biomass, heat pumps and waste heat recovery, and expanded their use of district heating systems.

In 2008, Swedish Environment Minister Andreas Carlgren credited Sweden's tax policy for cutting its emissions by 20 per cent below what levels would have been without it. "A carbon tax," Calgren told the Guardian at the time, "is the most cost-effective way to make carbon cuts, and it does not prevent strong economic growth."

The Swedish carbon tax is not identical to ours. Most prominently, it is much, much higher. Sweden's tax started at about twice the dollar-per-tonne rate that ours reached only this year, and the top rate has jumped to about $100 per metric tonne since its inception. On the other hand, many Swedish industries pay a lower rate (about $22/tonne), not all fossil fuels are covered, and proceeds go into general government revenues instead of tax cuts.

But the similarities between Sweden and B.C. are nonetheless striking. Both have a small population, widely dispersed across a forested, northern land base with just a few large cities. Both rely on a lot of hydro for electricity.

"When you look at B.C.'s policies," says Mark Jaccard, an environmental economist at Simon Fraser University, "you see the very same things we saw in the first years of the Swedish policy, which is the beginning of this disconnect between economic output and emissions."

Elgie finds that pattern repeated across the handful of other European countries -- including Finland and the Netherlands -- that have followed the carbon tax path. First there is a period of adjustment, as society begins to alter its behaviour and infrastructure in response to the higher prices. During this early phase, as in B.C., critics insist the tax is not working.

But, as Elgie points out, no one buys a new car or modernizes their factory every month. Yet if you know the price of energy will keep going up over time, fuel efficiency becomes a prime consideration the next time such an investment needs to be made.

The experience of others shows that 15 years on, carbon emissions can go down by five or six per cent with no negative impact on GDP. "The story we're seeing in B.C. is pretty much the same story that's already played out in countries with more experience," says Elgie. "Good for the environment, no harm to the economy."

Tweak the tax?

That's not to say B.C.'s carbon tax couldn't be made better, even in the eyes of admirers. It covers only about 75 per cent of our greenhouse gas emissions, for one thing. The rest, such as flaring from gas wells or non-combustion processes in cement and aluminum manufacturing, remain untaxed. "Let's go after that final 25 per cent," urges Mark Jaccard.

In particular, Jaccard fingers natural gas production as a growing emission source that could "swamp all of our efforts," unless we take action. "Tell them they can't emit (greenhouse gases) into the air, end of story," he says.

But gas facilities aren't the only places where emissions "leak" past B.C.'s tax: landfills, smelters and cement kilns are others. Jaccard's view? "Regulate everybody. Tell them they'll have to measure what is coming out. And, we're taxing you on it." Jaccard says this hard line could be phased in, however, to allow companies and regional districts time to prepare.

If that seems radical, note that such an approach has been taken before in B.C. In early 2007, BC Hydro had signed contracts to receive power from two coal-fuelled plants -- until premier Gordon Campbell decreed that all future sources of electricity must be zero-emission. The projects were promptly cancelled.

B.C. Minister of Environment Terry Lake agrees that industrial emissions should not be exempt from carbon pricing. It's just a matter of which carbon pricing scheme we use to capture them -- either the carbon tax, or a California-led regional cap and trade system that B.C. is still considering joining. "There are ways to capture those fugitive emissions and I quite agree that we should," he told the Tyee. "If we didn't want to go with cap and trade, we certainly could expand the carbon tax to capture those non-combustible emissions as well."

"Devil in the details"

Marc Lee, an economist with the Canadian Centre For Policy Alternatives, gives Gordon Campbell credit for bringing in "a policy industry did not want." But while other pundits laud B.C.'s carbon tax shift, Lee is underwhelmed. He doesn't buy Elgie's "early days" optimism.

"At $25 a tonne, the carbon tax is too small to have (created) any change in behaviour, even now that we're in the fourth year," Lee says. In his view, the tax must continue to rise each year, hitting $200/tonne by 2020, to really make a dent in our greenhouse gas emissions. But the tone of Lee's voice displays his pessimism about that actually happening. "We're languishing," he says. A November report from a B.C. government finance committee recommends the carbon tax be capped next year when it hits $30/tonne.

And while British Columbia has launched a climate action plan, we continue to subsidize the dirtiest sectors of our economy most responsible for greenhouse gas emissions. We're spending billions through our Gateway Program to expand freeways between suburban Langley and East Vancouver, and building power-grid connections to carbon-spewing resource companies for free. "We have to recognize this contradiction between what the left and right hands are doing," Lee says.

Lee also cautions against overstating the benefits of B.C.'s carbon tax. Any tax that makes fossil fuels more expensive is technically a carbon tax, sending a price signal to consumers and business to use less. He cites Ontario's application of the HST to gasoline and diesel as an example. Raising the tax in July 2010 from five per cent (under GST) to 13 per cent (with HST) created a higher tax on the carbon in a litre of motor fuel than our own B.C. carbon tax.

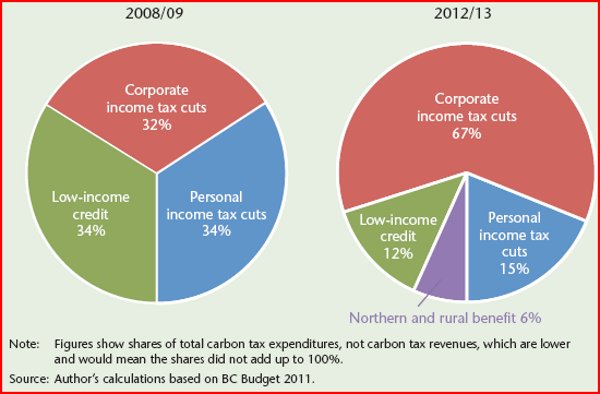

And in a report published in February, Lee points out that B.C.'s carbon tax is not "revenue neutral" as widely reported, but in fact "revenue negative." In other words, the B.C. government has given back $200 million more in tax cuts than it has actually collected from the tax.

Those tax cuts were based on the government's inaccurate projections of how much money the carbon tax would bring in. In addition to creating a gaping hole in public finances, the way the cuts were structured to favour business means that an ever-growing share of this foregone revenue will go to big corporations, at the expense of personal income taxes and support for the poor.

Lee challenges the idea that carbon tax revenue should be recycled to taxpayers at all. "Big chunks" need to flow to green investments as well as vulnerable British Columbians, he says.

"People may not like taxes, but when they do pay taxes, they expect them to pay for stuff like schools and hospitals," says Lee. "If we're going to have a carbon tax, it would make sense to be spending it on things like transit improvements, energy efficiency upgrades and green jobs."

Industry is feeling lonely

Jock Finlayson, a policy director at the Business Council of BC -- representing 250 of B.C.'s biggest companies -- insists he's not against carbon taxes in principle. "The biggest issue we have with the carbon tax isn't the design, it's the fact that we're the only jurisdiction in North America implementing it."

The scheme was implemented at a time when it was assumed many others would follow suit with carbon pricing, says Finlayson. But then came the crash of 2008, the rightward shift of federal Conservative leadership and, in the U.S., the Tea Partiers, surging gasoline prices and ongoing fears of economic collapse. The tax should not keep going up if B.C. continues to go it alone, he says.

The biggest problem moving forward, says Finlayson, is that for certain industries, like cement manufacturing, no "cost-effective" low carbon alternative products or technologies exist. Citing the tax as a disadvantage, cement industry reps claimed in March that Asian imports into B.C. were up about 15 per cent from 2008.

Stewart Elgie says the carbon tax must continue to go up to have the required environmental effect, but concedes that the most carbon-intensive industries need to be protected from "adverse economic effects." In the Swedish experience, for example, most industry pays less than the rest of society.

Others, like Jaccard, suggest the carbon price could continue to rise, but the amount of increase might be contingent on whether others join us in pricing carbon. For example, in setting its emission goals, the European Union devised not one, but two separate targets: A 20 per cent reduction by 2020 if they continued to go it alone, and a 30 per cent reduction if countries like China and the U.S. also got serious about emissions.

Marc Lee calls it absurd to give additional handouts to dirty industries that are already making huge profits by offloading the cost of their carbon pollution onto society.

"If we were to be aggressive in carbon pricing, it would dramatically undermine the competitiveness of industries like oil and gas, but that's the whole point," Lee says. "Weaning ourselves off dirty industries into clean industries... is going to create a lot more jobs than we are going to lose in oil and gas or mining."

Back to politics

The future shape of B.C.'s carbon tax may hang on how Gordon Campbell's successors interpret the concept of "revenue neutrality." Both the NDP and Christy Clark's BC Liberals are eyeing the huge amounts of money the carbon tax generates -- $848 million in the two fiscal years from mid-2008 to mid-2010. Both have suggested that revenue could do more than just cut taxes.

Therein lies political opportunity -- and hazard. About half of all carbon taxes in the world today fund carbon mitigation programs and government budgets. But to start spending B.C.'s carbon revenue -- even on "green" objectives -- after selling the tax to British Columbians as revenue neutral, only reinforces the kind of scepticism toward campaign promises that makes it so risky for politicians to impose decisive climate policy in the first place. The voting public, even those who want to do the right thing about climate change, already have enough reason not to trust politicians to keep their word.

Take Australia, where Prime Minister Julia Gillard first promised the public there would be no carbon tax. Yet, as these words are being written, Gillard has successfully created just that.

In Australia, as in B.C., the political dilemma is acute. If vote seekers are tempted to appease tax-fatigued cynics by stepping away from a carbon tax with bite, the latest scientific findings starkly reveal the cost of doing nothing. Just Monday, the United Nations weather agency announced that global concentration of C02 had exceeded most forecasts, hitting record levels.

Next Monday: B.C. has helped promote a "cap and trade" approach to reducing emissions -- but is the commitment still there? ![]()

Read more: Energy, Politics, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: