A nameless Second World War U.S. infantryman is reported to have said, "No war is ever really over until the last veteran is dead." By that measure, Canada's war in Afghanistan is still raging, and former Veterans Affairs minister Julian Fantino was effectively a wartime deserter in place, right from the start of his hitch to its inglorious end. But he was just following orders.

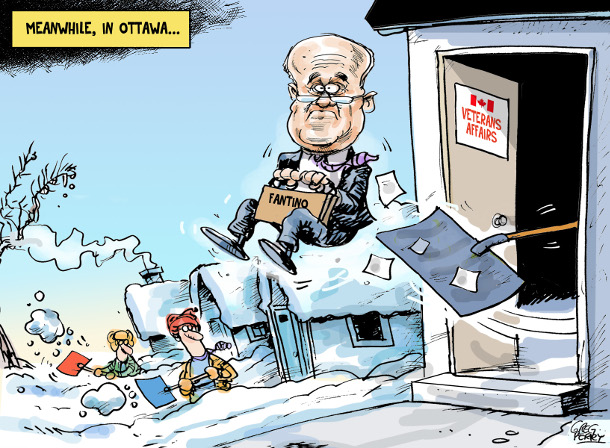

Fantino was turfed out of his job yesterday, after 18 messy and embarrassing months spent alienating both veterans and the serving military. Among other achievements, he cut $1.13 billion in Veterans Affairs spending and dropped a quarter of his ministry's staff. Meanwhile, the Auditor General reamed out the ministry for its slowness in providing mental-health services.

Fantino shut down ministry offices, stood up veterans who wanted to talk with him about it, and even cravenly ran from a veteran's wife. Some tough cop.

In one sense, Fantino was acting in a great Canadian tradition launched during the First World War, when politicians promised veterans they'd live in a "land fit for heroes" and then stiffed them when they got home. In another, he was just a good soldier, doing what his commanding officer's staff told him to do.

Back in the First World War, a half-mad, half-crooked war minister like Sir Sam Hughes could run amok for years before his political masters finally sacked him. But that was a different era, when MPs had their own power bases. Fantino was completely a creature of Prime Minister Stephen Harper and the Prime Minister's Office. He was reportedly approached by Harper before running as the acclaimed Conservative candidate in a 2010 byelection.

Proof of the Peter Principle

His narrow victory looks in hindsight like a proof of the Peter Principle -- that people rise in organizations until they reach their level of incompetence. Fantino had risen in police ranks for decades, surviving numerous controversies, and his career in paramilitary organizations made him seem suited for a cabinet post as associate minister of National Defence. But as military procurement boss, he mishandled the F-35 fighter jet file (in fairness, the Conservative position on that file was absurd), and was soon packed off to Veterans Affairs Canada in July 2013.

His misbehaviour in that office seemed to clash with the Harper government's professed pro-military position. But Harper has always been what the Americans call a "chickenhawk," a guy eager to have someone else fight his wars for him. While those who died in Afghanistan might take a last ride down the "Highway of Heroes," those who came back alive were an annoyance and a financial embarrassment. Hence the office reductions and unspent billion dollars.

Somehow the Conservatives have always framed themselves as supporters of the military, and suggested that questioning war is for cowards and spoilsports. Those who truly support our troops understand that it is a lifetime commitment: those who put their lives on the line for our sake have a permanent claim on us. To shirk that claim is to dishonour ourselves and insult all who have suffered and died for Canada over the past two centuries. And that the Conservatives have done.

Full disclosure: I am a veteran of the U.S. Army, honourably discharged in 1965 after two years of easy duty in Fort Ord, California. I cut the orders sending other guys to Vietnam, back when you had to stand in line to get there. (The rest of us, draftees and lifers alike, thought they were nuts -- as the classic Second World War Bill Mauldin cartoon put it, "That can't be no combat man -- he's lookin' for a fight.")

My first thousand-yard stare

By the time I got out, though, Vietnam was understood in the ranks to be reasonable grounds for draft dodging or desertion, and the next decade vindicated our view. After a couple of years of futile mass anti-war marches in San Francisco, my wife and I moved to Canada. There, as a young teacher, I met my first post traumatic stress disorder case: A young Canadian, one of those who had gone south to fight in greater numbers than Americans had come north to avoid fighting. He had the first thousand-yard stare I'd ever seen. He would not be the last.

If Vietnam had any redeeming value at all, it was that we learned you could go to war and come home physically unharmed but with a gravely wounded soul. The First World War's "shell shock" had morphed into the Second's "combat fatigue," supposedly a rare hazard for combat troops. Later research found that just one kind of person could survive 30 days of combat without psychological damage: psychopaths. That led, in my time, to U.S. Army research into LSD and others drugs to make you crazy enough for combat (I could have volunteered as a guinea pig).

But the brass and their political masters rarely suffer PTSD; Romeo Dallaire is one of the few generals I know of who came back with a case. It's a disease of the foot soldier, the beat cop, the firefighter, not the generals and police chiefs.

Hard decisions for other people

So Fantino, whatever shocks he experienced as a beat cop, overcame them to rise in a series of bureaucracies where "hard decisions" are easy for the decision-makers and hard for those who endure them. His boss, Harper, has been even better insulated, whether he was criticizing Jean Chretien for keeping us out of Iraq or spending unknown fortunes to bring war equipment home from Afghanistan. (It seems impossible to find the cost of that little housekeeping item.)

Presumably Harper feels equally insulated from the men and women he sent into harm's way, and whom he now finds inconvenient to support. And politically, that's a reasonable position. We were once a nation in arms, with the world's third-largest navy and over one million men and women in service. Every family had someone in that service, or had lost someone. Now the active Canadian Forces are about 68,000 -- about 10 per cent of the Canadian 2006 farm population of 684,000.

How many farmers do you know, even if you depend on them for your burger and fries? How many soldiers and sailors do you know, even if you depend on them for your life and liberty? Why should you care if some woman you don't know is terrified of her soldier-husband's drinking and violence? Or if parents you don't know are suffering because their soldier-son's violence is ripping the family apart, long after you could ever have found Kandahar on a map?

Fantino's unanswered questions

Those are the questions that Fantino couldn't answer because Harper didn't even want to answer them. He'd framed the suffering of the Canadian Forces as a sentimental story of Good versus Evil, where the hero's buddy may die, but not the hero (Harper) himself.

After the world wars and Korea and Vietnam, Canadian families went on fighting them for years and even decades, unrecognized and unmourned. Children born in the last 20 years are among the casualties, draftees in wars supposedly ended long before they were born.

Fantino, at 72 a year younger than I am, must have childhood memories of those silent postwar battles and their casualties among his friends. Perhaps he carefully forgot them, learning to rise in a society that rewarded amnesia.

Harper, born in 1959 when Canada was becoming a peacekeeper nation, was sheltered enough to grow up despising his own country as a welfare state and stupidly determined to return it to the savage capitalism that had led to the world wars in the first place.

Fantino followed him, and now Erin O'Toole has taken up the torch. Sometime this year millions of sheltered Canadians will vote to support a chickenhawk who spends Canadian lives like political poker chips, like Fantino and O'Toole themselves.

Or we will choose someone who, unless Canada is truly at risk, will not choose wars whose last veterans will die very late in the 21st century. ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Politics

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: