Among the questions that divide North American culture, this one's near the top: Will planetary salvation be achieved by creating new technology, or by returning to the natural world that created us? Google's purchase this month of Nest, maker of Internet-connected appliances that reduce household energy use, was a $3.2-billion bet on the first vision. Neil Young's recent Honour the Treaties tour, which had a stated goal of shutting down Canada's oil sands, was a step towards the second.

Both events were in some way a reaction to ecological crisis. Yet each helped push our culture in a different direction. Google is creating the future evoked by phrases like "Big Data" and "The Internet of Things," where technology largely determines Earth's limits. Young's tour resonated with those who may believe the opposite: that the "do-it-yourself" resilience of indigenous peoples, organic farmers and other seekers of "self-sufficiency" will allow us to more closely follow nature's rhythms.

This divide feels uniquely 21st century. But it may stretch all the way back to medieval Christianity. From this foundation of Western thought came two enduring utopian visions: one the basis for salvation by technology, and the other by nature. "You still see that tension today," said Arizona State University's Dr. Braden Allenby, who not long ago co-published a paper on it in Sustainable Development. "At issue are two very different ideas about the end point of human existence."

'Possessors of nature'

Now hold on. Allenby's reasoning requires you first accept an argument made by many social researchers: that potent ideas rarely emerge from nowhere. To be widely accepted they must build upon earlier ideas, just as those ideas once did, and so on in a cascade of human belief that can stretch thousands of years. That's how Allenby traced today's tech and nature divide to tensions in medieval Christianity. "The vocabulary is different," he said, "but a lot of the assumptions are the same."

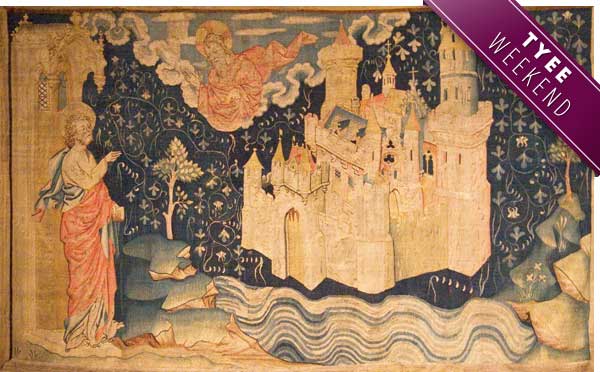

Some of the those assumptions may have origins in the New Testament's Prophecy of New Jerusalem. This Biblical vision of human progress towards a dazzling holy city influenced Thomas More's medieval conception of a futuristic "utopia." It was boldly reimagined by Francis Bacon in the 17th century as a scientifically advanced New Atlantis ruled by Christian technocrats. Bacon drew from a religious tradition, Allenby said, "that viewed technology as a means of... working towards the realization of God."

Even bolder was the vision of philosopher René Descartes, who like Bacon, his contemporary, argued that through technology people might become "like masters and possessors of nature." Descartes took the idea even further, forgoing the blatant Christianity of Bacon's utopian New Atlantis to envision an ideal society more recognizably modern -- one that would enable "man to create, from the raw material of nature, a modernistic temple unto himself," Allenby's paper argues.

Early environmentalism?

Others were reaching much different conclusions. Among the most formative was St. Francis of Assisi, whose 13th century thinking evoked the Old Testament's Garden of Eden to whose grace humankind should strive to return. Now regarded as the Patron of Ecology, St. Francis honoured "Sister Earth our Mother who sustains and governs us." He aimed, says one account, "to substitute the idea of the equality of all creatures, including man, for the idea of man's limitless rule of creation."

St. Francis was ultimately unsuccessful. Yet his thought influenced how the 18th century philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau "understood humankind's relationship with nature," Allenby's paper argues. Rather than the scientific and technological progress celebrated by Bacon and Descartes, Rousseau envisioned an ancient "state of nature" undisturbed by human activity, and a future agricultural society where people co-operated without the constant pressure of economic growth.

Echoes of this vision can be heard in Thomas Jefferson's conviction that farmers are "the most valuable citizens." Rousseau directly influenced Ralph Waldo Emerson, a seminal figure in modern environmental thought. Meanwhile, the techno-utopianism of Bacon and Descartes was embraced by early socialist theorist Henri de Saint-Simon, whose grand modernist visions, Allenby argues, laid the intellectual framework for U.S. conceptions of Manifest Destiny.

Tensions build

By the mid-20th century, both visions of salvation -- whether by technology or nature -- were deeply embedded in Western consciousness. Yet as the scale of humankind's impact on the natural world became harder to ignore, so too were the tensions between them. In the years following 1972's Stockholm Conference, which elevated ecological protection to the global agenda, "you had development people getting into more serious disagreements with environmentalists," Allenby said.

An international effort to resolve those tensions culminated in the 1987 Brundtland Report. Its roadmap for a "sustainably developed" global economy in effect fused two utopian visions traceable to medieval Christianity. "It was a way to overcome a very difficult political and intellectual issue while at the same time drawing from past human experience," Allenby said. Yet he's uncertain this union of economic growth to environmental quality truly settled the issue, or merely buried it.

More than 25 years later, there's still a profound cultural divide between the technology-rich future being built by companies like Google, and the appeal to a more natural state of human existence made by Neil Young's tour. As global crises like climate change get worse and worse, we'll be ever pressed to decide whether to seek a New Jerusalem, or return to the Garden of Eden. Can both visions ever be reconciled? Or will we forever remain, Allenby wonders, "arguing religion"? ![]()

Read more: Energy, Science + Tech, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: