Wildfires ripping through Alberta's boreal forest or what government officials call "freakish" firestorms are really a snapshot of how warming global temperatures and intensified insect infestations will change the nation's boreal forest, say scientists.

In the last week nearly 100 wildfires, battled by 1,000 forest fighters, have shut in billions of dollars worth of oil and gas facilities and forced the evacuation of 2,000 oil workers from Fort McMurray to Peace River.

One raging inferno, driven by 100 kilometre winds, destroyed a third of the community of Slave Lake north of Edmonton. That smoky region is also chock full of dead trees killed by the mountain pine beetle, another harbinger of changing global weather patterns.

Alberta's wildfires are very "consistent with what we'd expect for climate change," says Mike Flannigan, a senior fire researcher with Natural Resources Canada. "We are beginning to see fire episodes that are much more severe and much more common and not just in Canada."

Annual temperature changes in northern forests have risen two to three degrees over the last three decades due to warmer winters and springs. The temperature rise in turn has increased the risk of high fire danger from Siberia to Alaska.

In 2010 Russia experienced catastrophic wild fires that killed hundreds of people and blackened millions of hectares, while Australia experienced a similar calamity in its drought stressed forests in 2009.

Double the fires in Canada's forests

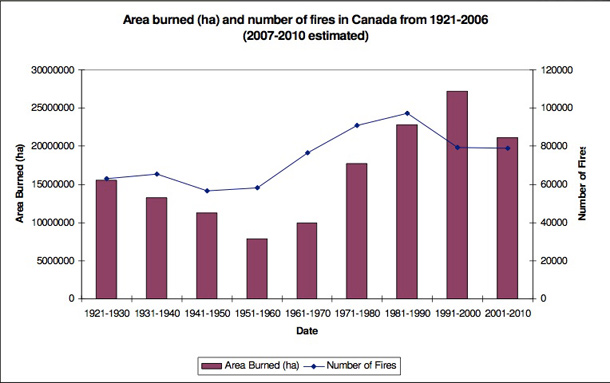

Despite expenditures of $800-million a year and some of the world's best fire fighting crews, the amount of forest area burned in Canada has doubled since the 1970s due to global warming. That now amounts to 2 million hectares a year, an area half the size of Nova Scotia. But the area burned by fires varies from year to year.

"Climate change is already impacting our forests," adds Flannigan. According to his research the annual area destroyed by fire could double again by the end of the century. Some fire forecasts for Alaska, B.C. and the Yukon expect fires to increase five-fold, and all due to warming temperatures.

With warming temperatures also come more lightening strikes. "And with more lighting strikes come more fire starts," explains Flannigan. Rising temperatures also make the forest drier. Given that temperatures are predicted to rise by four to six degrees Celcius, Alberta's forest will need 40 to 60 more rainfalls to stabilize the fire risk. But with climate change that's not happening, says Flannigan.

A massive bark beetle infestation may have also changed fire dynamics in the central part of the province around Slave Lake. In 2009 a long-distance flight of mountain pine beetles that rode wind currents from British Columbia dropped from the sky into the lower Slave Lake region. According to forest health officer Dale Thomas, the beetles killed millions of lodgepole pine.

New U.S. research says that recently killed lodgepole pine with red needles hold 10 times less moisture than green trees. As a consequence they ignite more quickly, burn more intensely and transport embers much further than fires in a green forest.

"Given there are so many fires at the moment, there is no doubt that pine beetle kills are affecting some of these fires," says Allan Carroll, one of the country's leading insect ecologists at the University of British Columbia. "The fire that got into town might have had something to do with the beetle but we don't know for sure."

Alberta Sustainable Resources has committed more than $200 million to fighting bark beetles with mixed results. In a petro state where nearly one third of the population and most Tory politicians do not believe that fossil fuel emissions have destabilized the climate, the agency makes little or no mention about the profound role that climate change has played in triggering and expanding the unwieldy insect outbreak.

"They don't mention climate change," says Carroll, "and I'm surprised by that."

'Novel environment for beetles to exploit'

Yet warming temperatures clearly triggered the event. A long and disastrous history of fire suppression created a uniform class of aging lodgepoles throughout the North American west. About 20 years ago climate change in the guise of warmer winters made it easier for the pine beetle and other bark beetles to reproduce and multiply. The aging forests in turn sustained the continent's second largest insect infestation since a plague of locusts devastated the west in the late 1870s.

Bark beetles, a remarkably diverse group of insects designed to collapse and renew old, drought-stressed or diseased forests, have killed approximately 30 billion trees from Alaska to New Mexico, changing fire regimes, rural communities and watersheds in the process.

Thanks to climate change the mountain pine beetle in B.C. expanded beyond its historic ranges, flew over the Rockies and colonized virgin lodgepole territory in north central Alberta. The insect has also established itself in jack pine, a conifer that extends across the country and that is perhaps Canada's most iconic tree.

Last April scientists at the University of Alberta confirmed that the beetles had successfully invaded pure stands of jack pine: "This once unsuitable habitat is now a novel environment for MPB to exploit, a potential risk which could be exacerbated by further climate change."

A 2007 report by the Alberta Mountain Pine Beetle Advisory Committee, which the Stelmach government did not release to the public, warned that the mountain pine beetle crisis "poses a serious challenge to government, industry and communities. The infestation is a difficult situation to manage and it is not likely that the beetle can be controlled."

Given the realities of warming temperatures in northern forests, the fire forecast will also be challenging, adds Flannigan, one of the country's top fire experts and a professor at the University of Alberta. The fire seasons will be longer; the area burned will be greater; fires will burn more intently; and the effectiveness of fire suppression will be uncertain.

"Fire management agencies may become overwhelmed with respect to climate-change-altered fire regimes," says Flannigan. ![]()

Read more: Energy, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: