[Editor’s note: This Labour Day week The Tyee is daily publishing excerpts from Drawn to Change: Graphic Histories of Working-Class Struggle, a new comics-style collection of stirring moments in Canadian labour history.

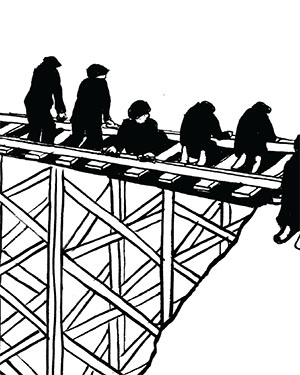

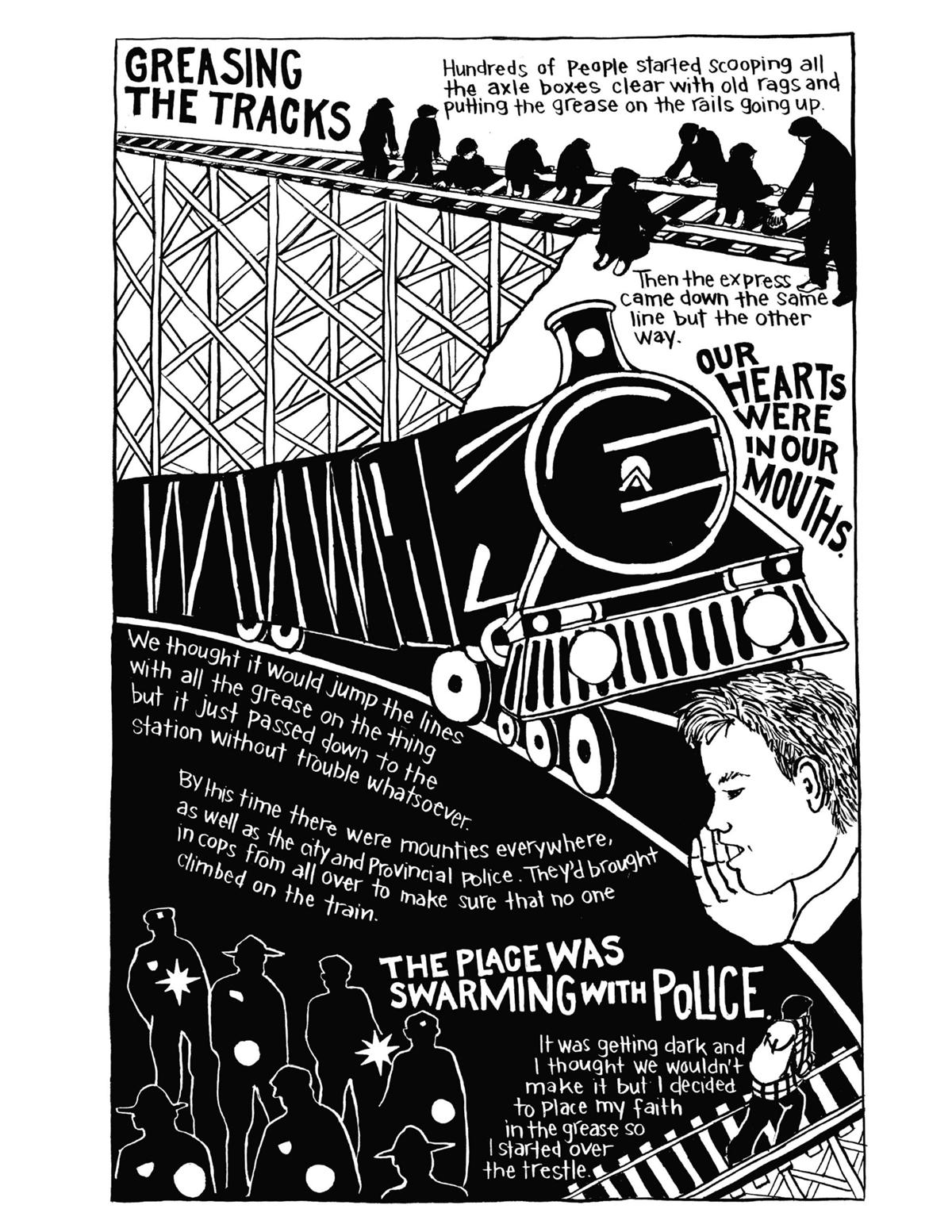

Today’s offering is from the chapter “Bill Williamson: Hobo, Wobbly, Communist, On-to-Ottawa Trekker, Spanish Civil War Veteran, Photographer.” As the title indicates, Williamson was a radical who seemed to be in the mix wherever the fight for worker justice was taking place during the Great Depression era. His first-person account is brought to life by writer/artist Kara Sievewright. Below, Williamson describes a scheme by out of work men to slow a train so they can hop on and join protests in B.C.

For more context, farther down, read Simon Fraser University labour historian Mark Leier on the life and times of Williamson. The work of Sievewright and Leier is excerpted with permission by Toronto-based publisher Between the Lines.]

THE LIFE AND TIMES OF BILL WILLIAMSON

Essay by Mark Leier

Through a combination of luck, temperament, conviction and choice, Bill Williamson was a participant in some of the most significant movements and events in working-class history, in Canada and globally.

As a teenager in British Columbia, he met members of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), also known as the Wobblies. Their message of radicalism, militancy, and rank and file democracy appealed to the independent young man, as did the union’s relaxed yet lively culture. One IWW song, by Matti Valentine Huhta, better known as T-Bone Slim, summed up Williamson’s life to that point:

I grabbed a hold of an old freight train

And around the country traveled,

The mysteries of a hobo’s life

To me were soon unraveled.

I ran across a bunch of “stiffs”

Who were known as Industrial Workers,

They taught me how to be a man—

And how to fight the shirkers.

I kicked right in and joined the bunch

And now in the ranks you’ll find me.

Hurrah for the cause—To Hell with the boss!

And the job I left behind me.

In B.C., the IWW led strikes of railway navvies, rallied civic workers, loggers and miners, and fought for the right of organizers to speak on city street corners despite being banned by local ordinances. The preamble to the union’s constitution made its politics clear: “The working class and the employing class have nothing in common…. Between these two classes a struggle must go on until the workers of the world organize as a class, take possession of the earth and the machinery of production, and abolish the wage system.”

State repression during and after the First World War, factional fights within the organization and the labour movement more broadly, corporate welfarism, and the depression of the 1920s meant the IWW’s formal strength had waned by the time Williamson met individual Wobblies in the camps and bunkhouses of the province. Its politicized working-class culture, however, infused and influenced the politics of generations of radicals, from those in the Communist Party and intellectuals such as C. Wright Mills to the Yippies of the New Left and activists today. That cultural legacy is as important as any of the bread and butter gains the union fought for.

By the 1930s, the Communist Party (CP) replaced the IWW as a centre of activism and radicalism. The Communist Party of Canada was formed in 1921 as radicals and workers from left-wing parties and unions hoped to replicate the success of the Bolsheviks in Russia by utilizing similar strategies and tactics. Historians still debate the role of the CP. Some see it as an authoritarian, sectarian party that was little more than a tool of Soviet foreign policy. Others point to rank and file organizers who were not much interested in the grand policy and political machinations of leaders at home or abroad. Instead, they were inspired by a broader vision and saw their organizing work sustained and supported by the institutions, such as newspapers, halls, legal aid and training the party provided. What cannot be denied is that Communist Party organizers were crucial during the Great Depression of the 1930s.

Williamson was one of many radicals who combined the earlier message of the IWW with the pragmatism of the CP to organize workers during the Great Depression. Unemployment soared to over 30 per cent of the workforce in some years while most unions did little more than retrench to protect the dwindling membership. While a new political party, the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation, now the New Democratic Party, was created in 1932, organizing the resistance by the unemployed was largely left to the Communist Party.

‘All Hell can’t stop us’

The success of CP organizers pushed the federal government to create relief camps to siphon off resistance and put unemployed men to work far from urban centres. Housed in crude barracks, clothed in army surplus, and forced to labour on make-work projects for 20 cents a day—the price of two packs of cigarettes—men found the conditions of the camps themselves reason to organize and protest, and the CP created the Relief Camp Workers Union (RCWU) to take up their cause. Demands for better conditions were backed up with protests and ultimately a strike of relief camp workers, who walked out of the camps and headed to Vancouver, where they won considerable support among the general public.

The most dramatic action of the RCWU was the On-to-Ottawa Trek. At one mass meeting of the unemployed, someone suggested that they take the fight right to the federal government. Why not jump on a freight train and head en masse to Ottawa? Party organizers were cautious, even timid. Riding the rails was illegal; individuals might escape the police, but how could hundreds avoid being spotted and arrested? More daunting, how could so many people be fed and sheltered and protected on a cross-country trip that would take several days? How could unity and discipline be maintained? But the idea caught the imagination of the rank and file, and organizers scrambled to gather supplies and tools for the Trek.

One of those tools was taken from the IWW: a song to carry the message of the Trek and to build solidarity. Legend has it that a “Comrade Marsh” had an accordion, but he only knew one tune, that of an American hymn, long since transformed by the English Transport Workers Union, the Knights of Labor, and the IWW into a labour song: “Hold the Fort.” Trekkers combined the traditional lyrics with a version written by Wobbly Ralph Chaplin in 1919 called “All Hell Can’t Stop Us.” The chorus became the rallying cry of the Trek:

Scorn to take the crumbs they drop us,

All is ours by right!

Onward, men! All Hell can’t stop us,

Crush the parasite!

While Williamson correctly observes that the demands of the Trekkers were not met, it would be a mistake to conclude the Trek was a failure. The dramatic tactic, its repression by the government, and the harsh reality of the depression moved Canadians to throw out the federal Conservative government of R.B. Bennett in 1935. Furthermore, the lessons learned by organizers were applied effectively as Communists and others created industrial unions such as the International Woodworkers of America and the United Autoworkers. Even Jack Munro, longtime Canadian president of the International Woodworkers of America and fervent anti-Communist, later reflected that whatever one might think of their politics, “the Communists were goddammed good trade unionists.” Those unions led the upsurge in union organizing during the Second World War and a wave of strikes across Canada during and after the war. That militancy warned successive governments and businesses that measures such as unemployment insurance, welfare, postsecondary education, medicare and fiscal policy to maintain full employment had to be at the top of their agenda. As we have seen over the last 30 years, without that sustained pressure, the state and capital will only squeeze us harder.

Thus Williamson’s story, told so evocatively in his own words and Kara Sievewright’s art, holds lessons for activists today. We need the spirit of internationalism that underlay the IWW and the International Brigade that Williamson joined during the Spanish Civil War. We need the inspiration that comes from a coherent radical vision and the creative, militant tactics that bring people together and empower them. We need organization—democratic, grassroots organization—to build mass movements and institutions to sustain it. And we need the glue of culture, a culture of opposition and resistance and humour. Part of that culture is the history of struggle and resistance. This graphic history beautifully recaptures some of our past and so helps us build the future. ![]()

Read more: Labour + Industry

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: