[Editor’s note: This Labour Day week The Tyee is daily publishing excerpts from Drawn to Change: Graphic Histories of Working-Class Struggle, a new comics-style collection of stirring moments in Canadian labour history. Today’s offering is from the chapter “Working on the Water, Fighting for the Land: Indigenous Labour on Burrard Inlet,” in which illustrator and lead writer Tania Willard of the Secwepemc Nation chronicles the rise of activism by Coast Salish people working B.C. docks.

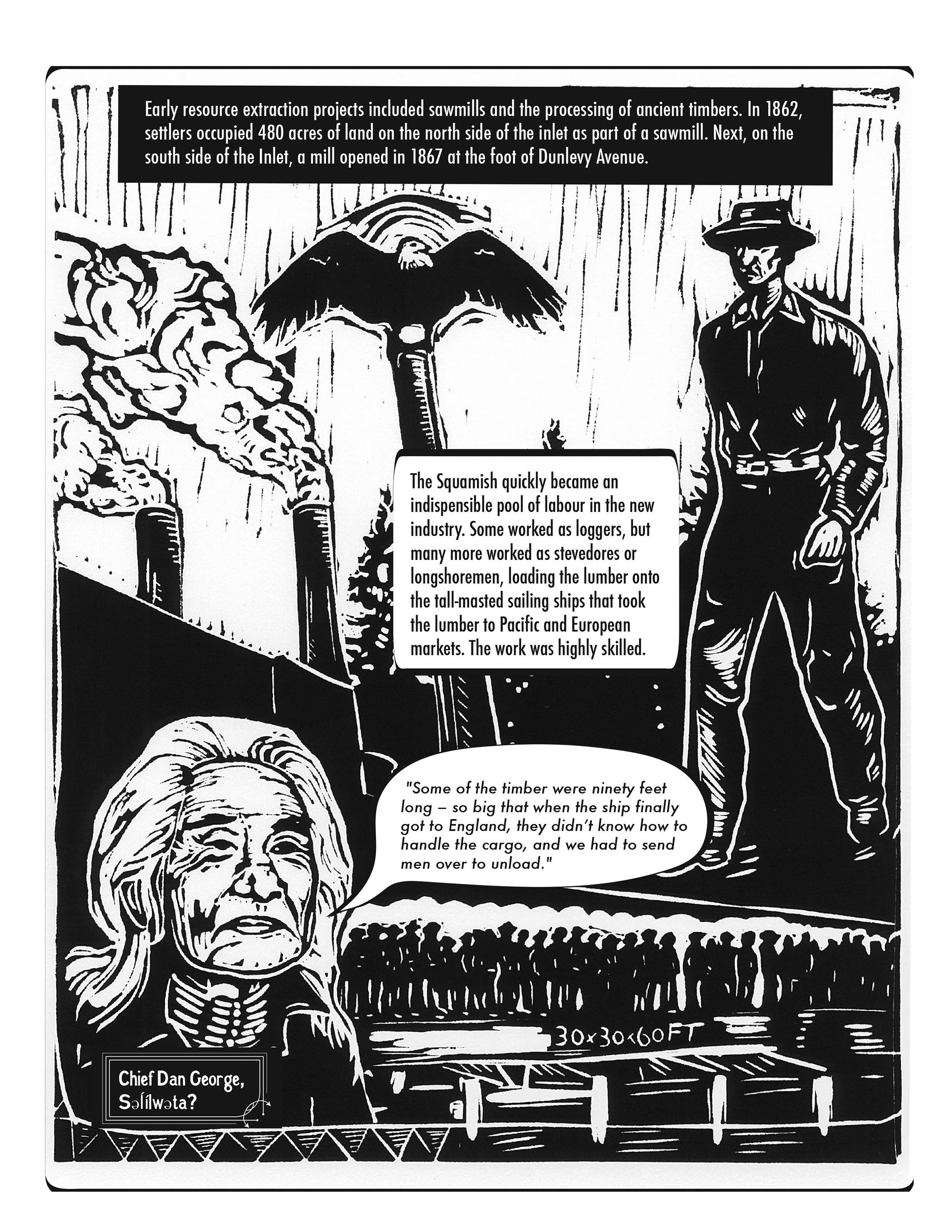

In 1859 the British Crown claimed all land in the area now known as Vancouver, never to sign treaties with the area’s Indigenous peoples. The stage was set for a cruel irony: An Indigenous labour force on Vancouver’s docks helped sustain an empire by transferring resources stolen from their own lands. Over the years those workers organized not only for better wages but to demand justice for their peoples. The page excerpted below relates how colonizing timber interests employed Squamish workers to load ships bound for England – and then unload the same cargo upon arrival.

For more context, farther down, read University of Cape Breton historian Andrew Parnaby’s essay “On the Indigenous Waterfront”. The work of Willard and Parnaby is excerpted with permission by Toronto-based publisher Between the Lines.]

ON THE INDIGENOUS WATERFRONT

Essay by Andrew Parnaby

This comic book tells the dramatic story of a group of Coast Salish peoples who were deeply involved in the political upheaval that characterized Indigenous and working-class lives in 19th and early 20th century British Columbia.

As Indigenous peoples, they felt the heavy pressures of white settlement. The appearance of sawmills along Burrard Inlet—part of their ancestral territories—beginning in 1863 heralded a new era of intensified settler colonialism. Yet, as workers, they took advantage of the employment opportunities that emerged as the port of Vancouver industrialized: they became longshorers. Never fully shedding their attachments to older, customary ways of Indigenous life and labour, they developed a sharp, well-defined consciousness of the issues that confronted them, both as “Indians” and workers: title to land and rights to resources; low wages, dangerous working conditions, and oppressive bosses. Consistently, this consciousness spurred political action, both on their reserves and on the job. Their solidarities extended to other Indigenous groups in the province and to non-Indigenous waterfront workers, who also faced hard times in the rough world of dockside employment. These are extraordinary lives worth knowing about—and learning from.

For an awfully long time, the writing of history ignored both Indigenous and working people. But beginning in the 1960s, the definition of who mattered historically began to expand and change shape; it became more open, more democratic. This shift in perspective was partly due to the activism of the era, as the Indigenous, women’s, labour, and civil rights movements gained momentum, forcing formerly hidden histories out into the open for broader consideration. That postsecondary education came within reach of people from diverse backgrounds was also important, for these new students wanted to learn more about people in the past whose lives more resembled their own. This comic book, as Paul Buhle explains in the preface, is indebted to this tradition. And in this spirit, it embodies two of the tradition’s most basic, yet enduringly powerful ideas: all peoples have a history and what they did, felt, and thought mattered.

This comic book also pushes that tradition in new directions. Until quite recently, Indigenous history and labour history were thought of as two distinct stories—researched and taught separately. Yet as “Working on the Water, Fighting for the Land” illustrates, the links between the two are too tight and too numerous to divide the historical narrative up so neatly. Lessons learned by the likes of Squamish leader Andrew Paull in the search for Indigenous solidarity and collective rights were also applied to the politics of waged work—and vice versa.

It’s not stretching the point too far to say that generations of Squamish men were—and continue to be—integral to the labour history of the Pacific province: their experiences propelled economic change, produced a range of influential unions, and shaded the electrifying political debates that raged on the docks and in the union movement down to the 1940s.

Inseparable and no less significant are the contributions of Squamish women, whose own history of domestic, community, and industrial work is hinted at in the comic book and exemplified by the figure of Valentina Brooks in the conclusion. Like the making of a traditional woven basket depicted on the book’s cover, each narrative—Indigenous and labour, male and female—is drawn together through the placement of text and image to make something new and original: history from below.

A graphic way of speaking

Visually this comic book is powerful. Yet perhaps more compelling are the stylistic elements that the artist—Tania Willard of the Secwepemc Nation—has brought to bear on this project. Non-Indigenous people have been representing “Indians” visually since the first illustrated edition of Columbus’s letters was published in the late 15th century. Prints, paintings, photographs, sculptures, and movies all followed—collectively entrenching the stereotypes of the “bloodthirsty savage,” noble savage, and dying Indian in Western visual culture. Utilizing the lino-cut style of print making, Willard offers readers an alternative to these malignant colonialist projections in her images of Indigenous peoples that capture their complicated histories, motivations, and actions. The arrangement of the images on each page in collage-like patterns extends this sentiment further. The layout weaves Indigenous people into the complicated patterns of historical change that transformed B.C.’s Lower Mainland during this era; it makes clear that they did not sit outside it all, unchanging, helpless, and thus in need of the white man’s pity or salvation.

Graphic elements borrowed from the visual traditions of the union movement—especially the Industrial Workers of the World—lend the comic book an additional, radical edge. That Willard has based some of her prints on photographic images originally taken by non-Indigenous photographers for other purposes illustrates in a few frames what the book, overall, is designed to do: change our perspective.

Reading a comic book is not like reading a traditional text. Its form forces the reader to move constantly from text to image, flit from panel to panel across the spaces in between, and thus to actively engage in the process of storytelling. In this heightened mode, readers might find themselves questioning commonly held beliefs about the past. Or perhaps they might be more open to the idea that history does not happen to people, but is made by them.

Readers might also stop seeing the present as the only or best way to organize a society, and start working to change it, as the “best men that ever worked the lumber” did in British Columbia not so long ago. ![]()

Read more: Labour + Industry

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: