Canadians whose politics are to the left of centre won't like to hear this: Stephen Harper and his Conservative-minority government probably are going to be in power a long, long time. Or, at least, as long as Harper himself wants.

This observation not only will disappoint (and infuriate) non-Tories; it likely also will surprise them. That's because nearly all members of Canada's vast punditocracy have declared that a minority government is, first, inherently unstable, and second, disappointing for Harper insofar as it is not the majority he is said to have wanted when he called the election.

These analyses, however, view Harper's minority from the wrong perspective. That is, they observe how far short the Tories fell from achieving a majority, rather than calculating the vast distance between the Conservatives and the official Opposition, the Liberals.

So, while it's true that Harper's Tories, with 143 House of Commons seats, are a dozen short of the 155 needed for a majority government, the point is largely irrelevant.

The key metric is that the Conservatives are a stunning 67 seats ahead of the Grits, who elected just 76 MPs.

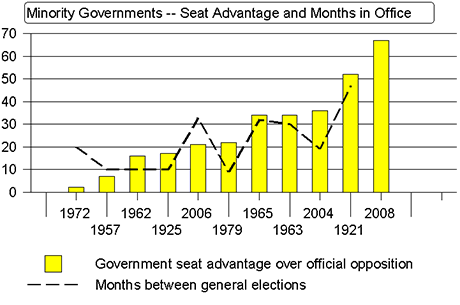

As the chart above illustrates, there is an interesting correlation between the seat-advantage a minority government holds over the official Opposition, and the length of time between general elections when the minority is in power.

Generally, the greater the seat-advantage for a minority government over the official Opposition, the greater the number of months before the minority again faces the electorate.

And, as is clearly shown in the chart above, Harper's Conservatives have just obtained the biggest seat-advantage of any minority in Canadian history. How astonishing would it be if, as a consequence of that enormous plurality, they also were to enjoy a longer term in office than any previous minority government?

Charting Harper's victory

In the chart above, the vertical yellow bars show, in ascending order from left to right, the seat advantage held by each of Canada's minority governments over its official Opposition.

Starting from the left, consider the first six yellow bars. After the 1972 general election, Pierre Trudeau's Liberals held a mere two-seat advantage over Robert Stanfield's Progressive Conservatives. The tally was 109 seats to 107.

Then, after the 1957 and 1962 general elections, John Diefenbaker's Tories had narrow seven- and 16-seat pluralities over the Liberals (led by Louis St. Laurent in the former tilt, and Lester Pearson in the latter). The Progressive Conservatives elected 112 MPs and the Grits returned 105 in the first contest; the numbers were 116 and 100 respectively in the second.

The fourth yellow bar shows that after the 1925 general election, Arthur Meighen's Conservatives held a 17-seat advantage in MPs over Mackenzie King's Liberals: 116 to 99. (See footnote below.)

The fifth is the 2006 federal general election, when Stephen Harper's Conservatives elected 124 MPs, and Paul Martin's Liberals had 103. The difference was 21.

Finally, in 1979, Joe Clark's Tories enjoyed a 22-seat advantage over Pierre Trudeau and the Liberals, with 136 MPs to 114.

To sum up, the six general elections considered here ended with minority governments, and those minorities all enjoyed a relatively small advantage in the number of seats -- ranging from two to 22 -- over the official Opposition.

The long and short of past minority governments

Consider now the black-dotted line for those same six general elections. The line represents the number of months between the general election that put the minority government into office, and the next, or subsequent, general election.

It is evident that just one of the minority governments elected in these six contests lasted longer than two years. Indeed, for four of those six minorities, the period between their initial electoral victory and the subsequent election was 10 months or less.

The exceptions were Pierre Trudeau's Liberals in 1972, which lasted about 20 months, and Stephen Harper's Conservatives in 2006, which remained in power for about 33 months.

Trudeau's minority lasted as long as it did thanks to support from the New Democratic Party (in return for the implementation of some NDP policies), while Harper's was aided by disarray in the opposition Liberal Party -- Paul Martin's resignation, a lengthy and divisive leadership convention, and the unwillingness of the new leader, Stephane Dion, to defeat Harper until the Grits had begun to reduce their party and personal debts, and developed new policies (notably the Green Shift).

It seems evident that minority governments with a comparatively narrow seat-advantage over the official Opposition usually stay in power for relatively brief periods of time.

(Merely as a point of interest, consider that the average seat-advantage these six minorities held over their official Opposition was roughly 14, while the average number of months from their initial election victory to the next tilt was about 15.)

Harper broke 1921 record

It is a different scenario for minority administrations with a larger seat advantage over the official opposition. Consider the next four yellow bars, representing Canada's general elections in 1965, 1963, 2004 and 1921.

Lester Pearson headed two Liberal minorities: the first after he defeated Diefenbaker's Progressive Conservative government in 1963, and the second after he bested the former prime minister in a rematch two years later. In the first tilt, Pearson's Grits elected 129 MPs, and in the second, 131. Dief's Tories, meanwhile, returned 95 and 97 respectively.

The Liberals' seat-advantage over the Progressive Conservative opposition following both contests was 34. Coincidentally, the time that elapsed between the 1963 and 1965 general elections was 30 months; and, between the 1965 and 1968 battles, 32 months.

Four decades later, after the 2004 federal general election, Paul Martin's Liberals enjoyed a near-identical 36-seat plurality over Stephen Harper's Conservatives. The Grits elected 135 MPs, while the Tories had 99.

One might have thought the Martin government would remain in power for about as long as the two Pearson minorities -- that is, nearly three years. But in November 2005, the three opposition parties combined in the House of Commons to defeat Martin's minority, as each calculated that a general election would strengthen their caucuses.

It proved a good move for the Conservatives, who gained 25 seats and formed a new minority government, as well as for the New Democrats, who added 10 MPs. The Bloc Quebecois largely treaded water, losing three.

All told, the Martin minority remained in power for only about a year and a half.

The final example is from 1921, when Mackenzie King's Liberals won 116 parliamentary seats -- just two shy of a majority. The insurgent Progressive Party was next with 64 seats, and the Conservatives trailed with 50.

The Grit seat advantage over the Progressives was 52, and, coincidentally, the King government did not face voters for another 47 months following their minority win.

Until the recent 2008 federal general election, the seat-advantage recorded by Liberals in 1921 was the largest in Canadian history. To date, the King government is the country's longest-lasting minority administration.

How media misread Tory victory

We come now to the election held Oct. 14, in which Harper's Conservatives captured 143 seats, and Stephane Dion's Liberals took 76. The discrepancy in seats between the minority government and the official Opposition is 67, now the biggest in Canadian history.

By law, Canada's next federal general election is scheduled for October 2012 -- four years from now. Should Stephen Harper's Conservatives remain in power until that time, they will become the country's longest-lasting minority government, surpassing by about a month that of Mackenzie King's 1921-1925 administration.

Of course, it's possible that the Liberals, Bloc Quebecois and New Democrats could all join together to defeat the government before 2012. But such a scenario, which seems unrealistic on its face, is at best a long way off given the near-certainty of another divisive Liberal leadership contest.

It's also possible that Harper, himself, could pull the plug on his minority administration at some point before the next fixed election date -- just as he did in September -- although such a move would make an utter mockery of Harper's own, now-tarnished, fixed-election law.

All of that seems a long, long way off, however. What we know for sure is that the country's news media yet again has misread the meaning of a Canadian election. Stephen Harper's minority government will be in power much longer than any pundit now foresees.

A footnote

The foregoing analysis defines a minority government as one that elected a plurality, and not a majority, of MPs in the preceding general election. Further, it references the number of months between federal general elections, which is not the same as the number of months a minority government actually was in office. There are several reasons for this distinction; here are the two most-obvious.

First, the 1921 general election left Mackenzie King's Liberals with 116 of 235 seats in the House of Commons -- two shy of a majority. Over the next four years, the Grits gained a parliamentary majority when Progressive MPs crossed the floor to join the government, but returned to minority status after losing byelections. In other words, although King obtained only a minority in the general election, he sometimes had a majority of parliamentary seats during the next four years.

Second, Arthur Meighen's Tories "won" the 1925 general election in the sense that they took more seats than any other party, 116 compared to 99 for King's Liberals. But King refused to leave the prime minister's office and, with support from the Progressives, continued to govern for about eight months.

Finally, facing defeat in the House of Commons, King asked the Governor General, Lord Byng, to dissolve Parliament and accede to another election -- a request Byng refused. (This is the genesis of the famed King-Byng affair.) At that point, in June 1926, Meighen became prime minister. Three months later, after the Meighen government was defeated in the House and another general election took place, King and the Liberals were returned with a majority.

Related Tyee stories:

- Harper Win Good for Campbell?

Provincial contest will be night and day different. - How Harper Gov't Pushed Financial Deregulation Here, Abroad

Way was cleared for US mortgage firms and easy credit, insured by Canadian taxpayers. - Federal election: Highlights of Tyee coverage

Read more: Politics

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: