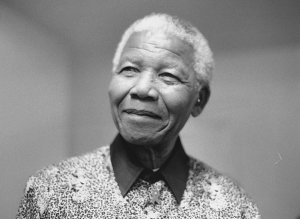

In the tsunami of coverage of the death of Nelson Mandela, little shows his real impact more than the pilgrimage of the world's leaders, including Canada's, to pay their respects to him.

Stephen Harper, along with our surviving PMs and former Governor General Michaëlle Jean, attended this week's memorial in Johannesburg.

They were scarcely noticed, but that was just as well; the leaders of the great powers too obviously suffered by comparison with Mandela. Barack Obama, almost as physically attractive a man as Mandela, and almost as eloquent, still found time to take a selfie with David Cameron and the Danish prime minister -- trivializing themselves in the process.

Mandela's death reminds us that we are generally ruled by political lightweights. They are not especially bright, only ambitious and lucky, and they lack anything like Mandela's character. Granted power, like our Conservatives, they indulge their spite against their adversaries. Through much of his life, Mandela was such an adversary, and therefore classed more often as a terrorist than as a freedom fighter.

For decades, one of the strongest fears among the post-imperial white nations of the west was that a black-ruled South Africa would launch and win a race war against the whites. It would be like the Haitians ousting their French slave masters, but on a far bloodier scale. The Afrikaners were a kind of racial embarrassment, because they had done what the European empires and their colonial offspring had also done, but wanted to forget: exploit and oppress the natives of conquered lands.

The European imperialists, exhausted after the Second World War, usually had the sense to know when it was time to go home. The Afrikaners, among the earliest colonials in Africa, had nowhere else to go, and no sense of how to compromise with the people they'd been oppressing. So they simply oppressed them harder.

Oppression as self-fulfilling policy

Oppression is a kind of self-fulfilling policy: You oppress those you consider unfit for full and equal status with yourself, and oppression soon proves you right: The oppressed often become very unpleasant people. They live for short-term pleasures because in the long term (like next month) they may be dead. They despise themselves and one another for enduring oppression, and the oppressor soon learns to pick off the potential rebels.

The oppressed usually engage in a guerrilla war against themselves, and only occasionally against their oppressors. Every crime by the oppressed becomes more evidence (loudly reported in the oppressor's media) of their unfitness for equality and more reason to increase the power of the police and military.

Yet no one is more oppressed than the oppressor: His every action is determined by his relationship to those he rules, on whom he depends for his prosperity and whom he rightly fears. And on some level he recognizes the injustice he inflicts; hence his angry defensiveness and assertion of moral superiority.

Playing the terrorist card

So from the 1960s, the apartheid regime stuck with the "Mandela is a terrorist" meme. His willingness to accept communist support, and to wage limited violence against the regime, was evidence enough.

But Mandela's violence was trivial compared to that of the Afrikaner army and police. Moreover, he was imprisoned for so long that memory faded. To white South Africans, jailing Mandela was sensible; they knew that killing him might trigger the race war they feared. Better to let him rot on Robben Island, out of sight and out of mind.

Prison, like any other form of oppression, does bad things to most people. That, after all, is the point; rehabilitation is the camouflage for our pleasure in inflicting vengeance and suffering. But in rare cases, like Mandela's, prison provided 27 years of reflection and thought, and he greatly benefited from it -- not least by learning Afrikaans and coming to know his oppressors far better than they knew him. As South Africa lost its overseas friends, and the country became ungovernable, Mandela changed from prisoner to negotiator and then, unexpectedly, to saviour.

The truly remarkable aspect of Mandela's success is that he was literally yesterday's man, out of touch with the world since the late 1960s. In one interview, he said he'd been frightened, on the day of his release, by the audio booms aimed at him by news crews; he thought they were some kind of newfangled weapon.

The time traveller

Yet this 71-year-old time traveller, pitched into the 1990s, still understood his country and how to save it. Retribution was pointless. Other anti-colonial leaders like Robert Mugabe and Idi Amin had turned on their white and Indian citizens (those who hadn't already left), and ruined their countries in the process.

Nelson Mandela's magnanimity marked a tectonic shift not only in South Africa, but in the world. The race war, dreaded for centuries, ended, like World War III, before it began. Like the dying Soviet bloc, apartheid went moribund with astounding speed. Politicians everywhere took note of the worldwide popularity of this old man who transitioned gracefully from prison to presidency. A few diehard Cold Warriors still muttered "terrorist" under their breath, but they were drowned out by the cheers of those Mandela had reprieved from catastrophe.

As a leader, Mandela disposed of more political capital than anyone else on the planet, granted him not only by his own people but by the world. Other governments were both bewildered and impressed. They had thrived for generations by blaming some scapegoat or other -- the Reds, the capitalists, the Jews, the Yellow Peril. Mandela seemed to show an alternative, shockingly radical way to take and sustain power: What George Orwell called "common decency."

Mandela brought no utopia. Violent crime continued. Ethnic battles were sometimes horrendous. Many whites emigrated anyway, not to save their skins but to make a better living elsewhere. He ruled for only one term, and took inadequate care of his succession. Not until his own son died of AIDS in 2005 did Mandela finally make it a political issue. By then the problem was out of control.

Even so, South Africa endured, and on Tuesday the world's leaders paid their respects. The heirs of centuries of imperial oppression and the cut-throat politics that sustained it, those leaders had to acknowledge, if only for one wet day, that he was not only his nation's saviour. He was theirs as well. He had played by the subversive rules of common decency and liberated his oppressors from themselves.

If they could learn Mandela's lesson, gain his insight, and muster his courage, our leaders might even gain a shred of his glory by trying common decency in their own countries. It might seem impossible; but as the master himself had written, "It always seems impossible until it's done." ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Politics

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: