In November, the City of Vancouver forged ahead with a bold plan to become the first Canadian city to decriminalize drugs in a move that could become a template for other cities and provinces.

Mayor Kennedy Stewart said the proposal could be approved by the federal government “within a matter of months.”

Stewart decided to push for decriminalization of drug possession in response to a horrific drug toxicity crisis that killed 1,723 B.C. residents in 2020, the highest number ever recorded in the province. The numbers look even worse for 2021, with double the number of deaths in the first three months of 2021 compared to the first three months of 2020.

Drug policy advocates had been asking for decriminalization as one way to make drug use safer.

But they now say the plan the city has submitted to Health Canada is so faulty that it could make the already toxic drug supply more dangerous and increase the involvement of police in the lives of people who use drugs.

People who use drugs, policy advocates and researchers say the problem is the amount of drugs the city has decided users will be allowed to possess without facing criminal charges. The threshold limits are too low and don’t reflect the daily lived realities of substance users, they say.

It’s apparent the police have had “unchecked decision-making power” over the development of the new model, they warn.

“Thresholds are a ridiculously archaic way of thinking you’re trying to somehow regulate how police interact with people,” said Karen Ward, a drug user, Downtown Eastside resident and advocate.

Ward said the guidelines the city has come up with don’t seem to take into account that much of B.C.’s drug supply is now made up of synthetic substances like fentanyl and benzodiazepines, and that setting a decriminalization threshold too low could lead to even more dangerous synthetic mixes.

“This is an entirely different era, this is not heroin, this is not ‘rock, powder, down’ anymore,” she said. The low thresholds could lead to the production of even more potent and deadly substances.

To implement decriminalization, the city must ask the federal ministers of health and public safety and the attorney general for an exemption to the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act’s provisions on possession of drugs for personal use within the city.

The senior city staffers tasked with creating the submission say that setting thresholds is a requirement of Health Canada.

If the submission is approved, police will never be able to charge people with possession if they are carrying an amount of drugs under that limit. If the amount of drugs is over the limit, police will have discretion on whether to charge people with possession or another charge, like possession for the purpose of trafficking.

For several years, the Vancouver Police Department has followed a policy of usually not charging people with possession, although they have continued to seize drugs — including very small amounts — and in some cases have charged people for possession for the purpose of trafficking.

That’s what happened to Samona Marsh, a member of the Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users, who served 90 days in jail in 2017 after she was caught with around one gram of crack cocaine.

“The commitment remains with [the police] to not charge people with possession, as much as possible,” said Ted Bruce, a public health consultant who is working with the city on the decriminalization submission.

“We’re going to monitor this to make sure there’s no increase, certainly, in possession charges above the floor.”

Some advocates pin the problem on outdated survey data the city used in developing its submission. It’s from 2018, and the drug supply has changed immensely since then.

But Thomas Kerr, a senior scientist at the BC Centre on Substance Use, said the threshold amounts chosen by the city don’t seem to reflect that data, which is from a long-running survey of injection drug users in Vancouver.

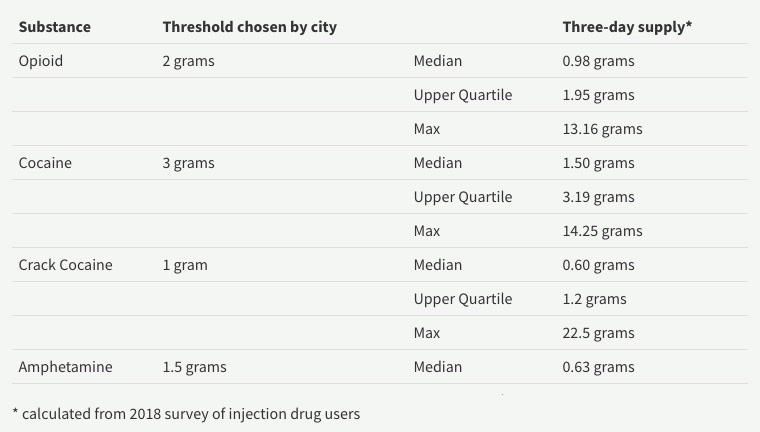

The city has chosen two grams as the threshold for opioids; three grams for cocaine; one gram for crack cocaine; and 1.5 grams for amphetamine.

Kerr said that is far below what the most vulnerable substance user consumes over three days, and the threshold should be set to at least match those users’ consumption.

“If you really want to protect the most at-risk people, you’d go with the maximum value of a three-day supply,” Kerr said.

For opioids, that’s 13.16 grams; 14.25 grams for cocaine; 22.5 grams of crack cocaine; and 19.35 grams of methamphetamine.

Kerr wants to know how the city came up with threshold amounts that diverge so wildly from what the data, and current drug users, suggest is needed.

Mary Clare Zak, the managing director of social policy for the City of Vancouver, said the working group was concerned that “possession of amounts that high would pose significant potential harms and risks, especially given the lack of safe supply.”

She said other jurisdictions that have decriminalized possession have included an “administrative mechanism” to “incentivize or require interaction” with health care if people are caught with larger quantities, which Vancouver does not plan to include in its proposal. The “mechanisms” include fines that are waived if people agree to seek health care for substance use.

Safe supply is prescription drugs that are prescribed to people with a substance use disorder as an alternative to tainted street drugs. While the government promised expanded safe supply before the fall election, a slow rollout has meant few programs are operating in B.C.

The Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users has now left a working group the city set up to help with the process.

In an open letter to federal Health Minister Patty Hajdu and decriminalization working groups for the City of Vancouver and B.C. government, a coalition of drug policy advocate groups said drug users were excluded from the process. The letter also says the Vancouver Police Department had too large a role in developing the model.

Bruce, the consultant working with the city, said the police were very much involved in developing the decriminalization model, and that was a requirement of Health Canada.

“They’re still illegal drugs, and the police are still going to be expected to deal with them,” Bruce said. “They’re illegal because they’re considered dangerous substances, and they’re controlled or restricted. So they have an enforcement mandate to deal with these those illegal substances.”

Bruce said there is a concern from the police with setting the threshold limit too high, because that could be used to mask drug dealing.

“I think there is a concern that it may make it easier for people to be able to do sales, with large amounts on them that get kind of under the radar,” Bruce said.

But Scott Bernstein, director of policy for the Canadian Drug Policy Coalition, said unrealistically low thresholds will push people to visit their dealers more often, raising the risk for them as they “have to go engage in a criminalized, illegal market more often.” The low threshold could also give police new reasons to search people and confiscate drugs.

“We’re sort of losing the entire intent of what decriminalization is supposed to do,” he said.

Bruce and the city’s Zak say the decriminalization model can be changed down the road.

But Bernstein said that with other jurisdictions like the B.C. government watching what Vancouver does and potentially using the “Vancouver Model” as a template, it’s important to get it right.

Bernstein said there’s another way the thresholds could have been set.

“You just talk to people, and I think the clientele for decriminalization starts with VANDU.... They’re at risk of being caught and criminalized and punished, and you can ask them about their actual consumption patterns are like, what they’re using, how much.

“That should have been the approach from day one.” ![]()

Read more: Health, Rights + Justice, Municipal Politics

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: