The planned open pit copper and gold mine that at one point included turning a lake sacred to the Tsilhqot’in Nation into a sludge pond appears finally stopped for good. The Supreme Court of Canada yesterday dismissed an appeal by Taseko Mines Ltd., after its proposed New Prosperity mine southwest of Williams Lake was previously rejected.

“We are celebrating the Supreme Court of Canada’s decision today, and taking the time to reflect on the immense sacrifices made by our communities and members to finally have their voices heard and respected,” Tsilhqot’in Chief Joe Alphonse said in a statement Thursday.

“This decision,” he said, “has been a long time coming.” That’s an understatement.

We republish an interview journalist Dawn Paley conducted with Alphonse on for The Tyee a decade ago, laying out the stakes for his people and their determination to oppose the project. Amidst the battle, Taseko dropped its plan to drain Fish Lake and use it to store mine tailings, but the Tsilhqot’in were never satisfied the project wouldn’t do serious harm to their territory. Here’s the headline and story from Oct. 11, 2010:

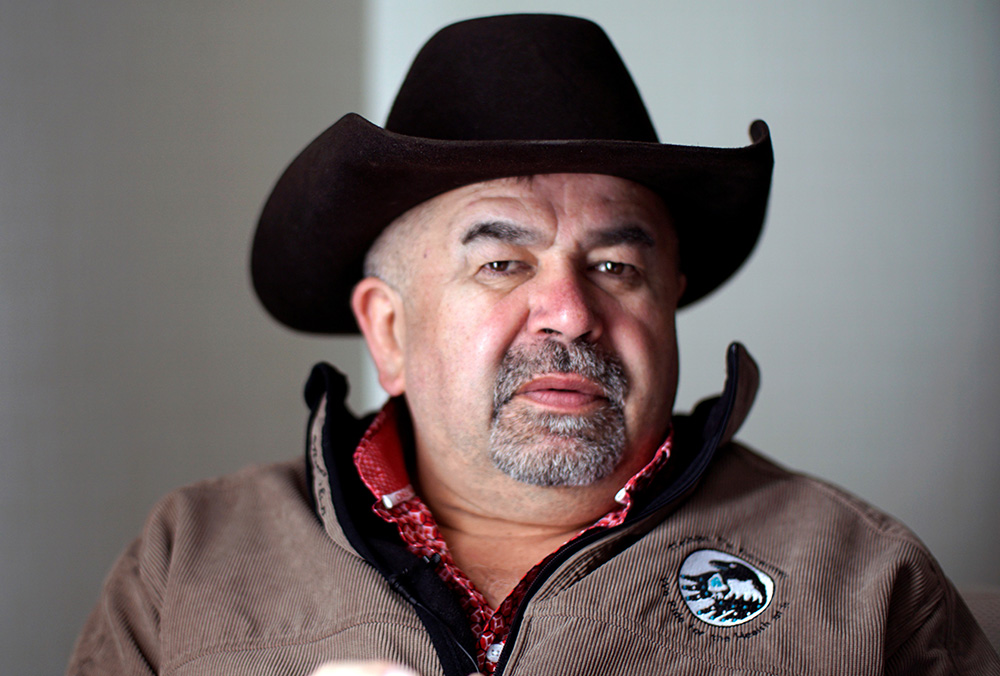

Fish Lake’s Top Defender, Joe Alphonse

If feds approve lake-killing mine, First Nations will escalate the fight, says Tsilhqot’in leader.

Attention on the conflict surrounding Taseko Mines’ proposed Prosperity mine is intensifying, but the man leading the fight against the project looked relaxed as he paused last week for a interview with The Tyee.

Joe Alphonse, the chair of the Tsilhqot’in National Government, was in town for a conference, offering him another venue for waging the fight to keep Fish Lake from being used as a tailings impoundment area.

Alphonse comes from a line of hereditary chiefs, and he’s tested the waters over decades in Tsilhqot’in politics, the last eight of which he’s spent as chair of the Tsilhqot’in National Government. He worked on the successful Xeni Gwet’in Tsilhqot’in case, in which Judge David Vickers concluded: “The Province has no jurisdiction to extinguish aboriginal title.... Land use planning and forestry activities have unjustifiably infringed Tsilhqot’in aboriginal title and Tsilhqot’in aboriginal rights.”

But even though they’ve proven their title to land covering 2,000 square kilometres in the Chilcotin Regional District, the Tsilhqot’in people are still up against the fight of their lives.

‘The impact’s going to be enormous’

Alphonse disparaged Taseko’s proposal to create a new lake where none exists to substitute for the one it seeks to fill with toxic waste. He said many British Columbians will feel the impact if a mine is built and Fish Lake is used to collect waste.

“If there is any spillage from the lake, the impact is going to be enormous, it’s going to be not just us as Tsilhqot’in people, but all users along the Fraser River downstream from us, and out in the ocean, the commercial fisherman, the tourist operators that depend on fishing for sockeye, chinook, steelhead, you name it, all of those people are going to be impacted,” he said.

Taseko’s proposed Prosperity mine passed the B.C. environmental review, but a federal panel found that the project would have “significant adverse environmental effects on fish and fish habitat, on navigation, on the current use of lands and resources for traditional purposes by First Nations and on cultural heritage, and on certain potential or established Aboriginal rights or title.”

The panel’s report is now sitting with cabinet, who will either give the green light to the project or prevent Taseko from going forward with the mine. The decision on the Prosperity mine was initially expected a few weeks ago. At this point, it is a waiting game.

“At the end of the day, even if the federal government approves this mine, that’s still not a guarantee that the mine is going to become a reality, because we would then be forced to continue to look after our interest,” says Alphonse. “If we have to get on the roads, we’ll get on the roads, if we have to step in the courts, we’ll step in the courts.”

During his interview with The Tyee, here’s what else Alphonse had to say...

On the Prosperity mine:

“In the early ’90s, we started finding out that there was this attempt by this company to create a mine at Fish Lake in the heart of Tsilhqot’in territory, undisputed Tsilhqot’in territory, there’s no overlap issues at that location with any other First Nation. We start working with them and we find out the enormous size of the project and the enormous potential threat to our fishery resource.... The more we learned the more fearful we got.

“During that time and era with a different federal government, the Liberal party was in federally and the NDP provincially, and it became very clear to the company that under those governments we would not get approval of this mine, so they stopped their attempt, they backed off. They said: ‘We will be back, we will be back when there’s a new provincial government in, and one that’s more pro-industry, and we will get this approved, we will do so thorough political process, not an environmental or technical process.’

“Not only is the NDP out provincially and there is a provincial Liberal party, but there’s also a change at the federal level as well, the Conservative party, who’ve introduced new policies.

“The one policy that we could always count on was ‘no net loss’ to fish habitat, and that’s where the most crucial change came federally. Now they’ve amended that policy, so if it can be compensated then they can grant projects such as this through.

“So this is a second kick at the cat.... This is their second attempt, and they’re pretty arrogant about their approach. I figure it’s a ’70s style approach, they’re trying to get big projects going, they haven’t consulted us to our level of satisfaction, and they feel they’re going to get this through by the friends they have within government, and that’s not the way to operate in a country like this.

“If their political process is a process where the rich person is going to be able to pay off politicians, then you know what? That’s not a process we want, and that’s not a government we want to represent us. If they’re going to push that through on merits as such, then at least we have hope that there will be avenues for us to protect our interests, and those avenues include going to court, and when you feel you’ve been unjustly (dealt with), that’s what the courts are there for.”

On the significance of rights and title over land:

“There are a lot of revenues that come from our land, the trees, the stumpage fees, people working within our territory, the taxes, you pile up all that money that’s being generated in our area, and you take into consideration the amount of money that the Department of Indian and Northern Affairs comes back and gives us, you know that’s not even a fraction of what they make from our land.

“We live on reserves, we’re to run our schools at 60 per cent of the rate provincial schools are run at, our health programs are inadequate, we have high diabetes, we have high you name it, and it’s all due to lack of funding, poor housing. When you live in such conditions, you know it’s almost Third World conditions, you have to speak up and do the best you can to represent your people and look after your interest, and in doing so it comes back down to the land, it comes to who has the right to rule that land.

“In the Xeni Gwet’in Tsilhqot’in case, that’s the closest a judge has ever come to actually acknowledging that they award total aboriginal title to the land. He stopped short of that to allow the parties to negotiate in a treaty table, in a land claims settlement. We went there, we went through the process. B.C. made a halfhearted attempt, Canada wouldn’t even entertain, they would not come and join us at that table.

“So as Indian people, if this is how we’re going to be treated, and we have the largest aboriginal rights and title case in B.C., in Canada, how is any other First Nation across the country going to fare? You know, I think this is such an enormous project, and it’s being closely watched. First Nations right across Canada want to see what happens, they want to see how the federal government deals with this: after all, the federal government has a duty to ensure good governance, and I think the signal that they’ll be pointing out is that they will not play by the rules, they will not play by their own recommendations, and that’s very serious, that’s a big issue.”

On the benefits of having Taseko Mines in Tsilhqot’in territory:

“They already have a mine that exists, that’s also sitting in Tsilhqot’in territory, and there is absolutely no working relationship with the Tsilhqot’in people on that mine. Alexandria is the most northern Tsilhqot’in community, between Williams Lake and Quesnel. Gibraltar (mine) is owned by Taseko. When you look at the Alexandria Indian Reserve, the corner post they have that [is] fenced off, there’s a road that runs by, and on the other side of that road there’s a gravel pit... of all the waste rock that Gibraltar mine dumps.

“But suddenly, when they say ‘yes’ to the (Prosperity) mine, all of that is going to change, they’re going to have this wonderful relationship with us, even though the company has had no working relationship whatsoever on any level with any First Nation anywhere.”

On the importance of Fish Lake:

“It’s a unique lake, it’s situated very high up on the mountains. When you’re at the lake, you look south from the lake and you’ll see glacier, snow, mountains coming straight out and you’ve got a gradual slope, and at the edge of the lake you have almost a sheer drop. If there’s a mine located there, anything that seeps from that mine is going to go directly into the Taseko River, which is a short river that feeds directly into the Chilko River system which is the largest (salmon) supplier over the last 10 to 15 years, (the) most consistent sockeye run. You know, in poor years that’s been the only decent run that we’ve had in British Columbia.

“As Tsilhqot’in people, the river people — that’s the translation of our name — we depend on fish, as a food source, and in lean years, years gone by, if salmon didn’t come back before European contact we went to places like Fish Lake, to Big Creek, to Anahim Creek, and we fish and use trout to get by.

“B.C. in the ’90s rated Fish Lake as one of the top 10 fishing lakes in the province. You know, it’s a lake where, you have a five to six-year-old child and you want to get them hooked on the outdoor life, bring them up there, take a three or four-foot stick, branch, whatever, tie some string to it, throw a metal hook on there, and I guarantee within five minutes that child’s going to be hooked on fishing. They’ll pull out their first fish ever.

“That is something that has taken thousands of years to create and there is no way a company such as Taseko (Mines) is going to come in and destroy that, and dig another hole in an area where the rocks they’re going to dig into are acid producing rocks, and they’re going to fill that up with water, and that’s going to sustain fish? No, I don’t think so.

“I think what we have here in British Columbia is so unique. When we live here in the province of B.C., we take for granted the natural beauty that’s constantly around us, and when you show pictures of the area of the lake and what and where they want to operate.... It’s a stunning view, it’s distorting such a nice pristine wilderness to a pile of rocks, and I think the farther you are from the project the more common sense you’re going to have about dealing with that. The (members of Parliament) locally here from Western Canada have taken away from the issue and created an Aboriginal vs. non-Aboriginal or Indian vs. cowboy type of scenario, and that should not be the issue. You know, stick to the facts.

“Throughout the summer we’ve had a huge return of sockeye salmon, we’ve had piles and piles of people lined up along the harbour buying fresh sockeye and you’ve got commercial fishermen out in the ocean talking about bringing their children out on the boats for the very first time, and just the pride and the joy that those people had in doing so, that’s what we’re trying to protect. There’s no way we can put a price on that.” ![]()

Read more: Indigenous, Rights + Justice, Politics, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: