[Editor’s note: Four years ago, a spike in home prices and rent rates spurred B.C. residents to call for change and politicians to respond with new taxes to prevent speculation, and funding to build housing. Then the COVID-19 crisis hit. In this special series, The Tyee focuses on how families are faring in Metro Vancouver’s housing market, whether new policies are making an impact, and how to build a resilient housing system post-pandemic.]

In 2005, Tom Lancaster and his wife bought a 510-square-foot, one-bedroom townhouse in East Vancouver.

Three years later they were starting to plan to have kids and wanted to move to a bigger place. At the same time, the bubbly Vancouver housing market was starting to turn down in the wake of a housing market meltdown in the United States.

So Lancaster and his wife sold, feeling fortunate to have come out ahead, and brought their first child home to a rented basement suite while they tried to figure out their next move.

Two years and two evictions later their family had grown to four with the birth of their son, and the Lancasters had had enough of Vancouver’s rental market. They decided to try to become homeowners again.

“We scraped together the cash that we had and put a down payment on a house,” said Lancaster, who works as a community planner.

“And it was the biggest money pit.”

The house in East Vancouver wasn’t fancy or big, but it was gobbling up all the money Lancaster and his wife had.

“It was the cheapest of all single-family houses on the market at the time,” Lancaster said. “It was a tear down.”

With his wife, a teacher, staying home to look after their two young children for two years, the couple found themselves scraping by on one income and struggling to make the mortgage payments. They decided to sell the house and buy something cheaper, like a townhouse or a condo.

But by then it was 2016 and prices were skyrocketing. Lancaster and his wife accepted an offer and sold the money pit. But while they waited for the actual closing date, prices jumped by around 30 per cent in their East Vancouver neighbourhood.

They were never able to buy again. Today they rent a house near Fraser Street in East Vancouver.

Falling off the housing ladder

Once a young Canadian couple gets a foothold on the housing ladder — a small “starter” house or condo — they’re supposed to be able to steadily climb upwards, moving to bigger digs as their family grows, and steadily adding to a home equity nest egg that will pay off once they get to retirement age.

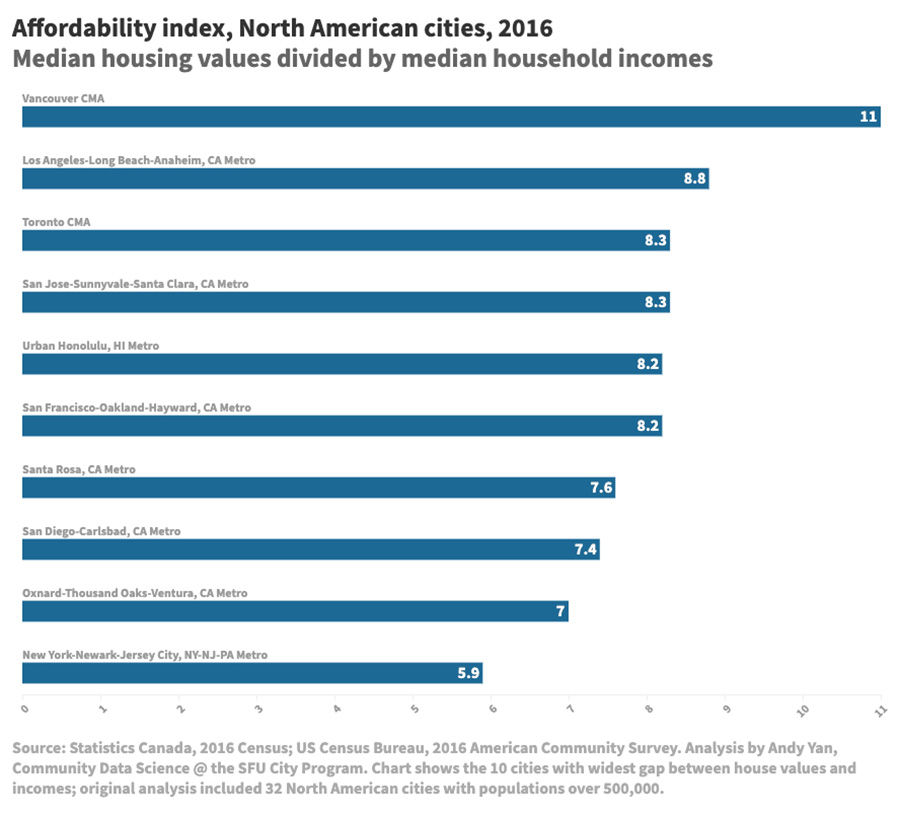

But in Vancouver some people have fallen right off the ladder, while many others can’t figure out how to get on it in the first place. Housing prices have risen so far beyond average incomes that it takes a big extra boost — a financial gift from family, often using a parent’s or grandparent’s Vancouver-area home equity — to get on the first rung of the ladder.

“Back in the 1970s... it took the typical young person five years of full-time work to save a 20-per-cent down payment on the average-priced home,” said Paul Kershaw, a professor at the University of British Columbia’s School of Population and Public Health.

Today it takes the average Canadian 13 years to save enough, said Kershaw, who is also the founder of Generation Squeeze, a lobby group for younger generations of Canadians.

In Ontario, that number rises to 15 years, and for B.C., it’s 19 years. If you’re trying to buy into the Greater Toronto Area, it would take you 21 years to save enough money. But Metro Vancouver tops them all: it now takes 29 years of full-time work to save a 20-per-cent down payment.

A country ‘drunk on housing’

University of Toronto professor David Hulchanski has tracked how Canadian government housing programs since the end of the Second World War have focused on boosting homeownership.

The federal and provincial governments created mortgage lending and insurance institutions, while municipal governments provided land and zoning to build “relatively cheap housing in postwar subdivisions,” Hulchanski wrote in a 2007 paper.

“Since the early 1970s, a steady stream of house purchase assistance programs has helped maintain Canada’s ownership rate at about two-thirds.”

The federal government created the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corp. in 1946, and the new agency “focused public funds almost exclusively on the ownership sector,” according to Hulchanski.

The federal government did step up efforts to provide subsidized rental housing for low-income Canadians in the early 1960s, building 200,000 units of public housing between 1963 and the mid-1970s with provincial and community partners.

Around the same time, federal tax breaks also fuelled a rental housing boom in Canadian cities.

But the social housing building boom came to an end in the early 1990s, when the federal government decided to get out of housing altogether — except when it came to homeownership.

Throughout the 1990s and 2000s CMHC focused primarily on insuring mortgages, and many federal and provincial budgets contained tax exemptions, credits or other benefits for homeowners, especially first-time buyers. One of the biggest giveaways to homeowners, an exemption on paying capital gains tax on the sale of a principal residence, has been in place since 1972.

By the mid-2000s, Hulchanski notes, CMHC was helping homeowners at a vastly higher rate than it aided poor people who were having trouble paying their rent. For instance, he says, CMHC reported it had provided mortgage insurance to 746,157 homeowners in 2005 alone, compared to the 633,300 social housing units it had funded in the past 35 years.

Canada was not alone in its focus on encouraging and subsidizing homeownership — many countries, including the United States, crafted policies designed to help people become homeowners. But in the wake of the 2008 U.S. financial crisis, which was triggered by a massive boom and bust in housing prices, experts and policy makers started to question the assumption that homeownership should always be the goal.

Today the head of CMHC, Evan Siddall, is relaying a much different message. Build more purpose-built rental — a lot of it. And stop peddling the idea that homeownership is “the only path to financial security.” He’s warned that in “supply constrained markets” like Vancouver and Toronto, measures to help people become homeowners only increase the price of housing.

“Well-intentioned support for home buyers often proves to have the opposite effect by making affordability worse, merely adding to existing homeowners’ wealth at the expense of younger Canadians,” he wrote in the agency’s 2018 annual report.

In remarks at a Feb. 13 event in Vancouver, Siddall summed up the city’s place in Canada’s housing continuum: “In a country that’s drunk on housing,” he said, “Vancouver is our No. 1 distillery.”

But the COVID-19 crisis has shown how CMHC is still set up to help homeowners quickly, but not renters. In response to the economic fallout, CMHC quickly announced it would support mortgage deferrals on March 13.

Siddall acknowledged the agency isn’t set up to provide the same immediate help to renters: “We actually don’t have an easy way to get support to renters quickly,” he wrote to The Tyee in March.

Instead, it’s been provincial governments that have acted to support renters, with eviction bans or extra financial support.

The best laid plans

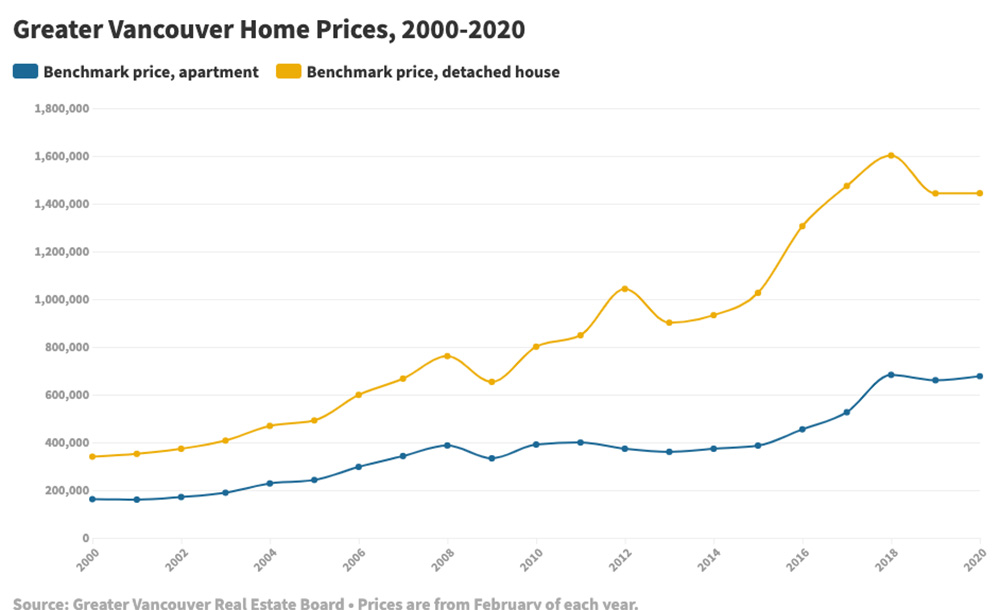

Vancouver’s housing market dipped slightly in response to the 2008 financial crisis — but the last 20 years have been a period of enormous gains for existing homeowners.

For residents trying to enter the market for the first time, or get back in, it was a different story.

Those who saved carefully for years could have their plans thrown awry by skyrocketing prices — or by unexpected events, like the addition of a new family member.

That’s what happened to Stefania Seccia and her husband, who cobbled together a down payment to buy a pre-sale condo in New Westminster in 2016. They used their savings and money that friends and family gave as wedding presents, and had just enough to pay a deposit and set aside a down payment for a $375,900 one-bedroom apartment in a project near Sapperton SkyTrain station.

The one-bedroom was all they could afford, and because Seccia and her husband had difficulty conceiving, they didn’t expect to have children any time soon. But that changed in 2018, when their son Max was born — a surprise, but a very welcome one.

Now the condo is almost complete and Seccia and her husband are trying to decide what to do. They currently live in a two-bedroom apartment in a housing co-op in Burnaby, and don’t really want to downsize to a one-bedroom with a toddler, a dog and a cat — especially now, with both parents working from home and taking care of Max because of COVID-19 restrictions.

But they also can’t sell and attempt to buy a bigger place right away, because they would have to pay capital gains tax on the sale of the brand-new condo. And while their one-bedroom condo has gone up in value, so have bigger units.

Seccia said she’s been advised she can move into the condo for six months and then sell in order to qualify for the capital gains tax exemption.

Financial uncertainties wrought by COVID-19 have also crept in. Seccia and her husband were recently approved for their mortgage, but they had to assure their bank that their jobs were “COVID-proof.” The approval is only in place until July, so they’re hoping the building will be complete before then.

The mortgage approval came as a huge relief, because if they hadn’t qualified they feared losing their pre-sale deposit.

But even with all the moving parts and hard decisions, owning their own home still seems like the only way to really ensure stability for the future.

“Anything can happen — a few years ago there was a problem with the federal government, whether or not they’d renew the [co-op’s] mortgage,” Seccia said.

“We just see homeownership as a way to secure our future. I kind of hate that that dream seems so unrealistic.”

The future of real estate

Starting in 2016, the federal and B.C. governments introduced new taxes and other measures to slow down real estate speculation and rapid price increases. Vancouver’s white-hot real estate market rapidly cooled in response. The slowdown was particularly significant for the highest-priced real estate in the market: the luxury condos of Yaletown and the West End, and single family homes in West Vancouver and Vancouver’s west side.

But in the first few months of 2020 it looked like real estate was again on the upswing, especially for the lower-priced part of the market.

Now with COVID-19 affecting every part of the global economy, it’s anyone’s guess. In March the BC Real Estate Association predicted home sales and prices would decline in the spring and early summer, “but should recover along with the wider economy in the second half of the year, contingent on the outbreak resolving.”

Others suspect the economic impact will be wider and long-lasting. Three million jobs were lost in March and April, Canada’s borders are still closed to non-essential travel and many prospective homebuyers are no longer able to get a mortgage because they’ve been laid off or work in a vulnerable industry.

Steve Saretsky, a realtor in Vancouver, said one of his clients was ready to put in an offer on a townhouse in late March. But when Saretsky followed up the next day, the buyer said he’d been laid off.

“I think a lot of people initially thought their job was safe,” Saretsky said.

Saretsky had a warning for the many Metro Vancouver residents who have been waiting for prices to fall so they can finally get into the market — not so fast. New condos are still being completed and unsold inventory is building, which should push prices down.

But he questioned how many buyers will qualify for a mortgage in the coming months.

“I just get the sense that everyone’s thinking, ‘I’m going to buy the dip, like this is my opportunity,’” Saretsky said. “Prices take a while to come down.”

“I just think people aren’t quantifying the economic destruction.”

Based on previous policy decisions, Saretsky expects senior levels of government will intervene to prevent housing prices from falling too far.

There are several policy tools the federal government could use, Saretsky said, like allowing longer mortgage amortizations or easing a mortgage stress test put in place in 2018 to make sure homeowners could weather adverse financial conditions.

With prices in Vancouver staying stubbornly high, can first-time buyers expect to be able to get into the market?

Shelly Smee, a realtor with Oakwyn Realty in Vancouver, said it’s still possible, but challenging. First-time buyers probably need to be on a high-earning career track and to have been saving for a down payment since their 20s, she said.

Most are also getting significant financial help from parents or grandparents, who are using their own home equity to help their kids.

Smee said around 70 per cent of the first-time buyers she works with today are in their late 30s.

“If you didn’t have a plan for your life in your early 20s, and you didn’t have the education or you didn’t get on a career path to earn some money, then yeah, it becomes very difficult in your 30s and 40s to realize that the market’s just kept going up,” Smee said.

Benjamin Tal, an economist at CIBC, said the Vancouver market went through “a very healthy correction” in 2018 and 2019.

But Tal doesn’t believe the city will ever again have affordable real estate prices. Instead, he says, residents who want to stay will have to come to terms with being life-long renters.

“I think that homeownership in Canada and in Vancouver in particular probably has reached its peak,” he said. “I don’t think people will be able to afford buying houses to the extent that they used to, and therefore you will see a situation where more people look for other opportunities.

“And you will see families renting, and that’s actually the future of real estate.”

Renting forever is hard to accept

To Seccia and Lancaster, that’s a hard pill to swallow. Both make solidly middle-class incomes. Seccia and her husband have lived frugally in the suburbs for years, putting up with a punishing daily commute.

“We keep getting told, if you climb the ladder, if you keep making more money, your situation will get better,” she said.

Lancaster said he sometimes feels like he’s failing to provide properly for his children. When he looks around his Kensington-Cedar Cottage neighbourhood, he sees multiple houses owned by one person — or houses owned by people who got hundreds of thousands of dollars in financial help from their parents — and it just doesn’t seem fair.

“All these other [families] are going to leave a multimillion home to their kids later on, and we’re going to leave our kids — hopefully — a place to rent,” he said.

Despite the economists’ mantra that building more housing will push prices down — or prevent them from rising further — Seccia believes that “high density developments are what’s causing prices to go up.”

Density has been steadily increasing, she said, with no impact on prices.

Lancaster supports measures aimed at reducing speculation, like Vancouver’s empty homes tax. But he’d also like to see more housing built everywhere — including in traditionally single-family home neighbourhoods.

“We need to build lots of rentals and lots of stuff to buy,” he said. “My neighbourhood is undergoing dramatic change and I love it.”

He’d also like to see the gap between homeowners and renters narrowed.

“I feel that housing is a human right and we live in cities where people are getting incredibly rich off of holding land and holding housing,” he said.

“The disparity between the people who own and those who rent is just so stark to us right now, it’s amazing.”

This article is part of a series produced with financial support from SFU Vancity Office of Community Engagement. Support for this project does not necessarily imply endorsement of the findings nor content of this report. Funders neither influence nor endorse the particular content of reporting. Other publications wishing to publish this series, contact us here. ![]()

Read more: Housing

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: