It's a good bet that few of the drivers and bus-riders streaming over the Granville or Cambie bridges in Vancouver spare much thought for the stretch of low-rise buildings, pathways, courtyards and green spaces that fill in much of the south shore of False Creek between the two overpasses. They should.

Created nearly 40 years ago in a rare alignment of federal, provincial and municipal leadership, the False Creek South community was, and remains, unique in more ways than one.

"One of the goals," recalls architect Michael Geller, who worked on the project for the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation in the early 1970s, "was to get a population mix that would replicate the population of Metro Vancouver."

An early convert to that goal was Monty Wood, another young architect who worked at the firm designing False Creek South's layout. One of the leaders of the project, he recalls, was senior architect Jos Verbauwhede.

Wood remembers the Belgian-born Verbauwhede as "a very odd man and a bit of a mystic, a mystic rationalist. A geomancer, that's what he called himself. He believed land had healthy nodes and unhealthy nodes, and there was a geometry that fitted to that."

When Verbauwhede worked, sketching ideas on paper with felt markers "like Picasso with a long paintbrush just going at it," Wood says, "it came out as an architectural expression, not in blocks but in these little walled cocoons with gradients of privacy and semi-public areas. It was very organic."

One day Verbauwhede returned to the office after a long weekend and unfurled a design 20 feet long and nearly as high as a person. It was unrolled, "courtyard after courtyard, cluster by cluster," Wood remembers. "There was a rationale for it: streets should be short, then you should have a bend. He wanted to make it as uncomfortable for automobiles as possible. To some extent, he succeeded."

Wood and eight architect friends were so enthused they hatched a plan to move into the community, in a building of their own design.

"To see that we could do something quite different and relatively unique in Vancouver -- that was compact, socially progressive, taking tired industrial areas and suddenly making them fabulous -- I thought, 'I wouldn't want to miss this,'" he says.

As the project neared completion in 1977, Wood had a fight with his girlfriend and drove down to the construction site with a sleeping bag and his dog. Camping out in his unfinished building, he was awakened around midnight by a boisterous party at a completed condo: newly occupied by Vancouver's then-mayor, Art Phillips.

"It was supposed to be a real community," he says, "not a suburban monoculture, but a mixed-use, mixed-income, mixed-ages. It was supposed to reflect the 'normal' demographics of Canada, as opposed to Kerrisdale or the Downtown Eastside. It had a real feeling of being ours. We were a little village unto ourselves."

A green space at its heart

The centrepiece of False Creek South is sprawling Charleson Park, noisy with duck ponds and an artificial waterfall, but also offering quiet forest walking paths and stunning views of Vancouver's downtown skyline and iconic mountain backdrop.

The ample green space, splitting the community into two sizeable clusters, was designed to compensate for what at the time was an untested population density for the city. Today, many residents describe the park as a highlight of life in the Creek, a place where children can safely play, adults can chat about community business on their strolls, and other Vancouverites can get a glimpse of what an urban setting planned for quality of life, not cars and freeways, looks like.

Charleson Park is flanked on both sides by the 170 units of the False Creek Co-operative Housing Association -- Vancouver's largest housing co-op -- roughly evenly divided to east and west. One of its first residents was Ana Maddox, who moved there in 1977 after immigrating from the former Yugoslavia.

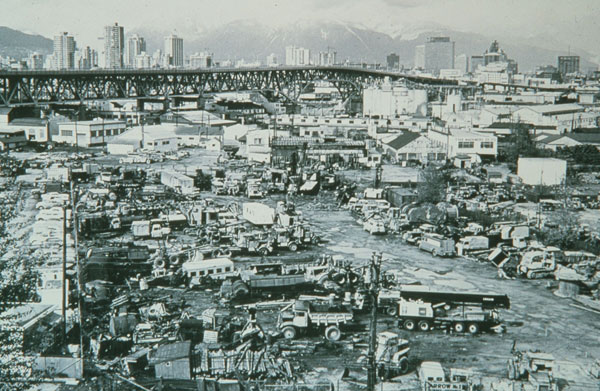

Maddox was attracted to the forward-looking vision of what at the time was a muddy, post-industrial wasteland beside a polluted harbour. She walked with me along a raised berm which mutes the noise from 6th Ave. and the railway tracks that run beside it. When she arrived, it was nothing more than a pile of fill excavated to dig the neighbourhood's foundations, dotted with spindly saplings. Today, they have grown into a quiet pine forest where crowds of dog-walkers amble daily.

A small town

To ensure a mix of working, middle, and upper-middle class occupants, one-third of its units were to be resident-owned condominiums. Beryl Wilson, at the time a modestly paid university employee, moved into one in 1979.

It seemed like "a crazy idea" to many, Wilson recalled. The condos were not cheap. Newspaper editorials and opposition city councillors scoffed at the blatant experiment in social engineering. But the moment she saw the emerging community, Wilson was intrigued.

"What it looked like to me was a small town," she says, pouring two cups of coffee in her small kitchen which opens onto an expansive common courtyard. "I'd always been curious about living in a small town, but I'd never done it. A little voice inside me said, 'There's your small town, where you'll know your neighbours and be part of a community.'"

Soon, Wilson was brainstorming social ideas over her back fence: evening "salon" discussion groups on environmental and equality themes, held in neighbours' suites; a local kids' bicycle festival; a childcare co-operative. Eventually she hatched the idea of launching a newspaper just for the neighbourhood. The Creek lasted several decades, issuing its last edition in 2002.

"It really was a funny, unique little newspaper," she chuckles as she leafs through a small stack of yellowed issues fished out of storage. "People used to say they liked it because it gave them a sense of community. That was its real value. It made people feel that they knew each other."

The community that unfolded often crossed the lines of owner, renter and co-op member. Wilson met Maureen Powers early on and the two became fast friends. Powers left the community but later returned to live in a co-op unit. She still marvels at the audacity of the insight that building a community meant marginalizing the automobile.

"It was based on getting people out of their cars," Powers says. "They anticipated a certain percentage of people just would not have a car. There's transit right outside the door, why would you need a car? That was forward thinking a long time ago."

Beating the predictions

Rider Cooey was another original co-op member. They were pioneers of sorts. Nothing was established, and residents had to figure out how to make their own community decisions, set up internal rent subsidies for low-income residents, create a governance structure that would last the life of the neighbourhood. The Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation provided funding and early training to set up committees and manage the finances, but Cooey was struck by both the level of democratic empowerment and responsibilities of co-op life.

He takes pride in having defied the initial "great hostility" to False Creek South's progressive vision and eccentric design. "There were hostile editorials," he says. "It was predicted to fail because it was too dense. They thought people can't live at that level of density. They compared us to rats in mazes."

"I've raised two batches of kids here," Cooey adds, sitting at his kitchen table surrounded by children's drawings. "It's been a wonderful place to raise kids -- the waterfall, the beach, the rocky creek, the muddy stream, the small and big pond -- it's all totally artificial, but it works perfectly as a little bit of nature in the city right outside our door."

While the handful of different co-ops in False Creek South form the largest concentration of that housing form in the province, a key intention of the community plan was that one-third of its residents would be low-income renters. A number of nonprofit societies took responsibility for running several rental complexes, or 'enclaves' as locals call them.

Wilma DeVito moved into the first of several False Creek rental suites in 1986 and now lives in the largest such enclave, Vancoeverden Court. Minutes from the waterfront and surrounded by green space, it's affordable housing unlike almost any other. Operated by the New Chelsea Society, the blue-painted complex features staggered balconies, semi-private backyards, and Verbauwhede's snowflake-like nested courtyards. We meet in one of these.

"I don't like high-rises," DeVito says, waving to the condominium towers lining the north shore of False Creek. "I wouldn't live in one. This is perfect with three floors. It feels secure."

Like many renters here, DeVito feels a strong sense of ownership and belonging, even though she's neither condo-owner nor co-op member. "The nature of the dwellings -- where some people own, some rent, some are in co-ops -- it's a real mix of accommodation, from kids to 90-year-olds," she says, where renters have a sense of 'home' in the community too.

A high-risk project

Not all has been perfect in False Creek South: more on that in tomorrow's report. And not everything has worked out as Verbauwhede or the project's political godfathers planned. The bustling plaza designed to give a feel of European café life never materialized, scuttled by residents who complained about noise and city planners who doubted there was enough business to keep most shops afloat.

Still, some joked that the vision of a liveable neighbourhood has worked perhaps a little too well: Few have wanted to leave, regardless of their changing income levels, mobility needs, or departed children. Even in the rental buildings, DeVito seldom sees moving trucks or people leaving.

One early enthusiast who no longer lives in False Creek South is Monty Wood. He was forced to move out recently when he was unable to refinance his condo: banks were spooked by the uncertainty hanging over the project's future tenure on land the city leased to residents four decades ago... until 2036.

Tomorrow, the finale of this series: Why False Creek South may need to change in order to secure its future. Find the series so far here. ![]()

Read more: Housing, Urban Planning + Architecture