The earth-shattering exploitation of deep deposits of shale rock for natural gas production has broken global records in northeast British Columbia and now threatens critical water supplies across the country, warns a new Munk School of Global Affairs report by award-winning B.C. journalist Ben Parfitt.

Earlier this year at Two Island Lake north of Fort Nelson, two corporations, Encana and Apache, blasted an estimated 5.6 million barrels worth of water along with 111 million pounds of sand and unknown chemicals to fracture apart dense formations of shale over a 100 day period, or what Parfitt calls "the world's largest natural gas extraction effort of its kind."*

During the massive operation in the Horn River Basin, one of the world's largest shale gas deposits, the two companies completed 274 consecutive "stimulations," or mini earthquakes, to break open the pores of gas-bearing rock along horizontal reaches stretching an average of 1.6 kilometres underground.

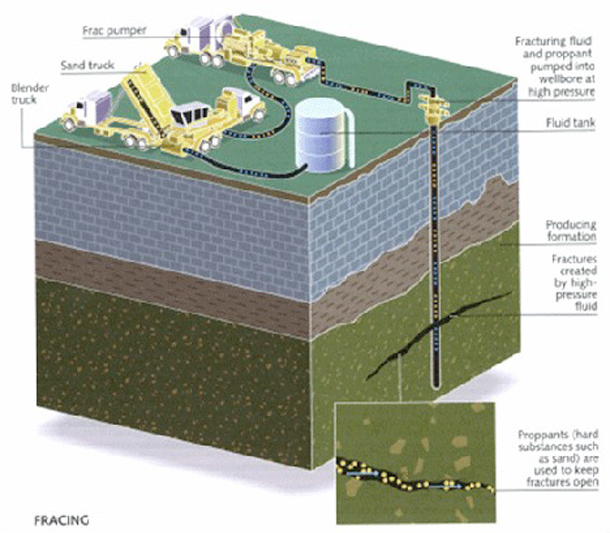

"Hydraulic fracturing," a brute force technology used in 90 per cent of all unconventional oil and gas well drilling, has allowed companies to exploit vast shale deposits across the continent over the last decade.

Vast reserves, huge risks

Shale gas, the bitumen or "dirty oil" of the natural gas world, requires more energy, water and toxic chemicals than conventional gas production, because massive amounts of concrete-like rock must be broken open to release small pockets of methane. In addition, many shale deposits are rich in contaminants, including CO2, hydrogen sulfide and radioactive materials because of the depth of the resource.

Given that the volume shale gas produced in the United States has grown from zero to 20 per cent in the last 10 years (shale reserves may even offer a 100 year supply for the continent), groups as varied as the Fraser Institute, MIT and the Cambridge Energy Research Associates have proclaimed shale gas as "a game changer" for energy security.

Many experts argue that shale gas could retire coal-fired plants or slow down the deployment of wind and solar projects altogether. Others contend that shale formations deplete too quickly to offer secure supplies for the future. At the same time, the "shale gale" has also created abiding controversies about water use, groundwater contamination and the regulation of the industry from Wyoming to Quebec.

Fracture Lines, commissioned by the Program on Water Issues at University of Toronto's Munk Centre, now only sheds light on the scale of development from British Columbia to New Brunswick but highlights industry's largely unregulated water use.

"In the absence of public reporting on fracking chemicals, industry water withdrawals and full mapping of the nation's aquifers, rapid shale gas development could potentially threaten important water resources if not fracture the country's water security," concludes Parfitt.

In contrast to the United States, where U.S. Congress and state regulators have begun public policy debates about the shale gale, "neither the National Energy Board nor Environment Canada have yet raised any substantive questions about the shale gale or its impact on water resources."

BC's water-intensive shale gas industry

In British Columbia alone the shale gas industry now has permits to daily withdraw up to 274,956 cubic metres or 60,481,864 imperial gallons from 540 creeks, rivers and lakes as well as aquifers in northeastern B.C. In contrast Greater Victoria, home to 336,000 citizens, uses but half that amount of water every day, says Parfitt, who has written extensively about B.C.'s forestry industry.

Talisman Energy, a company that has also secured access to 2,400 square miles of Unita Shale formation underneath rich farm lands along Quebec's St. Lawrence River, has proposed diverting 2.2 million cubic metres of water per year "on a permanent basis from B.C.'s largest man-made water body, Williston Reservoir" in order to develop its B.C. assets.

In addition "a single permit held by Encana gave it access to water at 71 different locations for a combined daily maximum of 16,117 cubic metres or nearly six-and-a-half Olympic swimming pools worth of water per day."

Yet little is known about quantity or quality of surface water or groundwater in the region. One quarter of creeks and lakes remain unnamed.* In 2009 industry and Geoscience B.C., "a self-described industry-led, industry-focused applied geoscience organization announced the first phase of research to characterize groundwater reservoirs in the area."

A 2009 report by government hydrogeologist Elizabeth Johnson confirmed that while drilling has increased rapidly in the Horn River Basin, "geologic knowledge is still highly limited especially in the centre portion of the basin." To date B.C. lacks comprehensive groundwater legislation adds Parfitt.

Moreover the fracturing of deep rock formations with water, sand and chemicals appears to be a chaotic, non-linear process that can open fractures to freshwater formations as well as other oil and gas wells.

Widespread contamination in U.S.

Anthony Ingraffea, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at Cornell University and one of the continent's foremost experts on fracking, told Partiff that as soon as highly pressurized fracking fluids "gets through the cracks that you have created and reaches a joint system that has been there for many years, the joints open in unpredictable ways."

To date B.C.'s Oil and Gas Commission (OGC) has reported 18 "fracture communication incidents" in which sand or chemicals injected into one well abruptly pop up in nearby gas wells 670 metres away. According to the investigative journalism group, Pro Publica, similar events have resulted in the contamination of 1,000 groundwater wells in shale gas plays in places such as Wyoming, Pennsylvania, Texas and Colorado.

Fracking chemicals or what industry calls its "secret sauce" can be highly toxic and involve hundreds of chemicals, including silicas, petroleum byproducts, potassium-based chemicals and alcohols. In the Marcellus Shale, a huge deposit stretching from New York to Tennessee, industry leaves as much as 3 million gallons of contaminated water in the ground for every well drilled.

Various U.S. regulators have demanded full disclosure on these chemicals.

The Munk report also notes that shale gas can create an enormous amount of greenhouse gas emissions and is rarely as "clean" as advertised by industry and government. A 2009 study of the Texas Barnett Shale, for example, found that emissions from compressor stations and production activities from 7,700 oil and gas wells emitted 33,000 tonnes per day of CO2 in 2009, or the equivalent of two 750 MW coal-fired power plants.

(Encana's shale gas processing Cabin Gas Plant will emit 2 million tonnes of GHG a year, while Spectra's two shale gas plants will release nearly 3 million tonnes. That's as much climate-changing pollution as a small oil sands operation.)

Energy in, energy out

The energy returned on energy invested (EROI) for unconventional resources can be dramatically poor.* Although no regulator now demands the reporting of EROI for shale gas formations, calculations on oil shale extraction show a return of two joules for every joule of energy invested, says Parfitt. In contrast, conventional or high quality oil and gas yield returns of 15 to one.

Given the growing scale of concern and government studies on hydraulic fracturing and impacts on drinking water in the United States, Parfitt tables 13 recommendations in his Munk report.

They include the mapping of all aquifers prior to shale gas exploration; the transparent reporting of water withdrawals and wastewater production as well as the full disclose all toxic chemicals used in fracking operations.

Given the extraordinary size and scale of shale gas formations in B.C. and Quebec, Parfitt recommends that both provincial governments "establish commissions to examine the potential and cumulative impacts on water resources, energy use, government revenues and carbon emissions."

Natural gas production from Peace River country now represents the largest source of revenue for the government of British Columbia (as much as $4 billion some years) and is regulated by the Oil and Gas Commission. The OGC, described by Peace River farmers and ranchers as more a facilitator than a regulator, is 100 per cent funded by industry levies.

(Full Disclosure: Andrew Nikiforuk has written two studies on water issues for the Munk School's Program on Water Issues.)

*Story update at 7:30 p.m., Oct. 15, 2010. ![]()

Read more: Energy, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: