[Editor's note: This is the second of eight excerpts from Patrick Condon's new book Seven Rules for Sustainable Communities: Design Strategies for the Post Carbon World. This series, running Wednesdays and Thursdays for four weeks, offers just a sampling of Condon's vital guide for green planning; interested readers are encouraged to seek out the book.]

U.S. and Canadian cities built between 1880 and 1945 were streetcar cities. It was a time, very brief in retrospect, when people walked a lot but could get great distances by hopping on streetcars.

By 1950, this system was utterly overthrown, rendered obsolete by the market penetration of the private automobile. Both walking and transit use dropped dramatically afterward, all but disappearing by 1990 in many fast-growing metropolitan areas.

The collapse of that world constitutes a great loss, because the streetcar city form of urban development was a pattern that allowed the emerging middle class to live in single-family homes and was sustainable at the same time. Streetcar cities were walkable, transit accessible and virtually pollution free while still dramatically extending the distance citizens could cover during the day.

The planning literature occasionally refers to the streetcar city pattern, but seldom is the streetcar city mentioned for enhancing human well-being or lauded as a time when energy use per capita for transportation was a tiny fraction of what it is today.

This is tragic, because the streetcar established the form of most U.S. and Canadian cities. That pattern still constitutes the very bones of our cities -- even now, when most of the streetcars are gone.

To ignore the fundamental architecture when retrofitting our urban regions for a more sustainable future will fail. It is like expecting pigs to fly or bad soil to grow rich crops.

Accepting this premise, it may help to examine the forces that spawned this distinctive urban pattern and to understand which of these forces still persist. A "day in the life" story will start to reveal this genesis and help us read more clearly what remains of this urban armature.

Mr. Campbell buys a home

The year is 1922, and Mr. Campbell is house shopping. He has taken a job with Western Britannia Shipping Company in Vancouver, and his family must relocate from Liverpool, England.

He plans to take the new streetcar from his downtown hotel to explore a couple of new neighbourhoods under development. A quick look at the map tells him that the new district of Kitsilano, southwest of the city centre, might be a good bet. It is only a 15-minute ride from his new office on the 4th Avenue streetcar line and is very close to the seashore, a plus for his young family.

When he enters Kitsilano, he finds construction everywhere. Carpenters are busy erecting one-storey commercial structures next to the streetcar line as well as very similar bungalow buildings on the blocks immediately behind. As Mr. Campbell rides the streetcar farther into the district, the buildings and active construction sites begin to be replaced by forest; the paved road gives way to gravel.

Soon the only construction seems to be the streetcar tracks themselves, which are placed directly on the raw gravel. The streetcar line seems out of place in what appears to be raw wilderness. Taken aback by the wildness of the landscape, Mr. Campbell steps off the streetcar where a sign advertises the new Collingwood Street development.

Here, things are more encouraging, as workers are laying new concrete sidewalks and asphalt roads. Stepping into the project's show home, he is immediately surrounded by activity.

Carpenters and job supervisors waste no time inviting Mr. Campbell in, offering coffee and dropping him in a seat before the printed display of new homes. All the homes fit on the same size parcel or "lot," with the bungalow detached, single-family home the predominating style.

The formula

Mr. Campbell has many questions, but getting to and from work every day is his most important concern.

"Well then, sir, how do I know I can get downtown to my job from here dependably?" asks Mr. Campbell.

The salesman smiles and says, "Because we own the streetcar line, of course! Naturally, we had to put the streetcar in before we built the houses, and a pretty penny it cost too. But nobody will buy a house they can't get to, will they?

"The streetcar lines have to be within a five-minute walk of the house lots or we can't sell them. But we make enough on the houses to pay off the cost. If we didn't, we’d be out of business!

"But there have to be enough houses to sell per acre to make it all work out financially. We have it down to a formula, sir: eight houses to the acre give us enough profit to pay off the streetcar and enough customers close to the line to make the streetcar profitable too.

"That's why all of the lots are the same size even when the houses look different. You're a business man, Mr. Campbell. I'm sure you understand, eh?" he says with a smile.

Minutes from shopping

"But what of commercial establishments, sir?" asks Mr. Campbell with reserved formality. "Where will we buy our food, tools and clothing?"

"Oh, all along 4th Avenue, sir. Don't worry! By this time next year it will be wall-to-wall shops. One-storey ones at first, to be sure, but when this neighbourhood is fully developed we expect 4th Avenue to be lined with substantial four- and five-storey buildings to be proud of.

"Liverpool will have nothing on us! You'll always be just a couple of minutes from the corner pub. Anything else you need, you can just hop on and off the streetcar to get it in a tic."

Mr. Campbell was sold. He was overjoyed to be able to buy a freestanding home for his family, something only the very rich of Liverpool could afford. All of the promises the salesman made came true more quickly than Mr. Campbell imagined possible, with the single exception of the four-storey buildings on the main commercial street. Rather than 10 years, it would take another 80.

First, the Great Depression froze economic activity; then the Second World War redirected economic activity to the war effort. By the 1950s, the economic pendulum had swung toward suburban development fueled by increasing car ownership. Not until the 1990s, during the decade of Vancouver's most intense densification, would the vision of four- storey buildings lining both sides of Kitsilano's 4th Avenue be realized.

The streetcar city principle is not about the streetcar itself; it is about the system of which that the streetcar is a part. It is about the sustainable relationship between land use, walking and transportation that streetcar cities embody. The streetcar city principle combines at least four of the design rules discussed in the following chapters: (1) an interconnected street system, (2) a diversity of housing types, (3) a five-minute walking distance to commercial services and transit and (4) good jobs close to affordable homes.

For this reason, it is offered as the first of the rules and as a "meta rule" for sustainable, low-carbon community development.

40 per cent still live there

Close to half of urban residents in the United States and Canada live in districts once served by the streetcar. In these neighbourhoods, alternatives to the car are still available and buildings are inherently more energy efficient (due to shared walls, wind protection and smaller average unit sizes).

Most of these districts are still pedestrian and transit friendly, although with rare exception the streetcar and interurban rail lines that once served them have been removed (Toronto is a rare example of a city where the streetcar lines remain largely intact).

While there is much debate about what precipitated the demise of North America's streetcar and interurban systems, one thing is certain. In 1949, the U.S. courts convicted National City Lines -- a "transit" company owned outright by General Motors, Firestone and Phillips Petroleum -- for conspiring to intentionally destroy streetcar systems in order to eliminate competition with the buses and cars GM produced.

While it may seem impossible to envision today, Los Angeles once had the largest and most extensive system of streetcars and interurban lines in the world. In a few short years, this system was completely dismantled by National City Lines, at the same time that an enormous effort to lace the L.A. region with freeways was launched.

Today, no hint of this original streetcar fabric remains. Only by perusing old photos can one sense the extent of the destruction.

Now, some 60 years later, elements of this system are being painfully replaced at great cost. The L.A. area Metrolink system has restored some of the historic interurban lines, while inner-city surface light rail lines have replaced a small fraction of the former streetcar system.

Cars, buses, streetcar, or heavy rail? A case study of the Broadway Corridor in Vancouver

Broadway, the dominant east-west corridor in Vancouver, has always been a good street for transit, even after the streetcars were removed. The corridor has a continuous band of commercial spaces for most of its length that are within short walks of residential densities greater than 15 dwelling units per acre to ensure a steady stream of riders and customers on foot.

Residents who live near Broadway can survive without a car. Many of the residents along the corridor are students at UBC who have always enjoyed a one-seat ride to school on buses with three- to five-minute headways (or frequencies, the length of time between one bus leaving and the next arriving).

More than half of all trips on the corridor now are by bus, with over 60,000 passenger trips per day. Very frequent bus service has reinforced the function of the Broadway corridor even without the streetcar in place. Buses are both local, stopping every second block, and express, stopping every one to two miles.

The street has no dedicated bus lanes, although in some portions curb lanes are transit only during peak hours. Walkable districts, sufficient density, three-minute headways, hop-on-hop-off access to commercial services, and five-minute walking distance to destinations at both ends of the trip all contribute synergistically.

The buses on Broadway work very well; if they were never upgraded to streetcars, it would not be end of the world. But the corridor, because of its high ridership, is a candidate for substantial new transit investments.

Using a modest amount of proposed funds to restore streetcars to Broadway makes good sense. Streetcars will reduce pollution, better accommodate infirm and elderly passengers, add capacity, provide everyone a more comfortable ride, cost less per passenger-mile over the long run than is being spent now, and attract investment where it is most desired.

What is the optimal transit system?

What evidence exists that streetcars are more cost-effective over the long term than either rapid bus transit, which the corridor has, or heavier "rapid" transit, such as the SkyTrain, which is being proposed?

To get a useful answer to this question it must be further asked: Cost-effective for what? Over what distance? To serve what land uses? The question quickly becomes complicated.

It helps to start by asking what the optimal relationship is between land use and transit, and what transit mode would best support this optimum state. Similarly, how do an increasingly uncertain oil supply and rising concern over GHG emissions factor into our long-term transportation planning?

Investment decisions made in Vancouver and elsewhere over the next 10 years will determine land use and transportation patterns that will last for the next 100 years. How can we choose the system that helps create the kind of energy, cost and low-GHG region that the future demands?

A research bulletin completed by the Design Centre for Sustainability at UBC compiled the information needed to begin to answer these questions. The results are organized in the context of three basic sustainability principles: (1) shorter trips are better than longer trips, (2) low carbon is better than high carbon and (3) choose what is most affordable over the long term.

The importance of walking

First, shorter trips. It does us no good to shift car trips to transit if average transit trips become longer and longer over time. Eventually energy and resource reductions will be eaten up by increased vehicle miles travelled per person on these new transit vehicles.

If shorter vehicle trips are the long-term goal, what then is the best option to achieve it? In traditional streetcar neighbourhoods, local buses and streetcars extend the walk trip, allowing frequent on and off stops for trip chaining (performing more than one errand on the same trip) and accommodating typically short trips to work or to shop when compared to other modes. Thus, the walk trip is the mainstay mode of movement in streetcar neighbourhoods, with the streetcar itself acting as a sort of pedestrian accelerator, extending the reach of the walk trip.

While both buses and streetcars are effective ways to extend the walk trip, streetcars are much more energy efficient than both diesel and even somewhat better than electric trolley buses. Electrically powered vehicles also give the flexibility to incorporate "green" sources of energy into the mix -- electricity from hydro, wind or solar power that could in time completely eliminate carbon emissions from the transit sector.

But even streetcars that get their energy from coal burning power plants generate far less GHG per passenger mile than diesel buses, as electric vehicles are far more efficient in converting carbon energy into motive force than are internal combustion engines.

Counting the costs

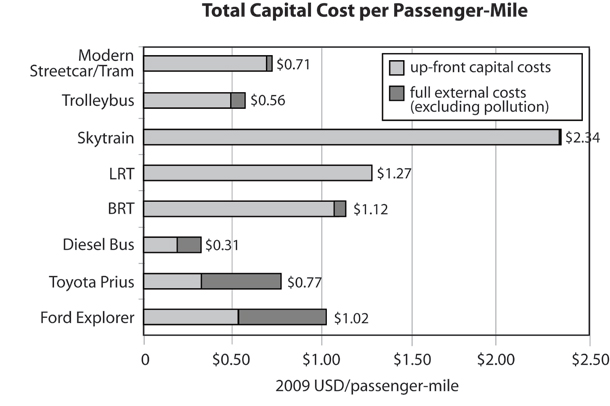

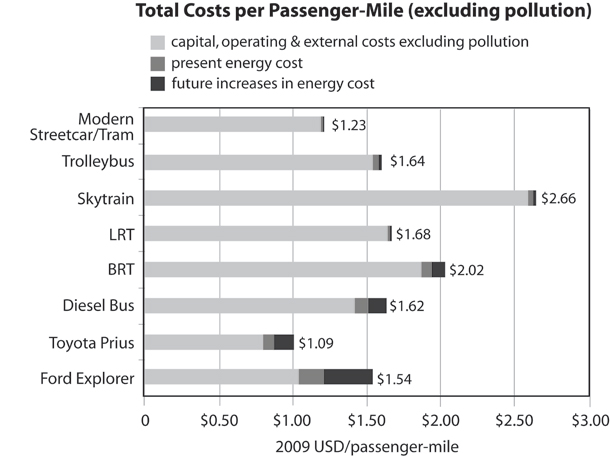

The capital costs for transportation modes such as streetcar, LRT and SkyTrain are relatively easy to determine, because the large initial investment to build the transportation infrastructure (tracks, platforms, stations, etc.) is generally tied directly to the project.

However, many costs associated with personal automobile, local bus service and to a lesser extent bus rapid transit and trolleybus are more difficult to determine because they operate on existing roadways, the construction and maintenance of which are not included in most cost calculations for these modes.

For this reason external costs that begin to place a value on the land and resources dedicated to automobile infrastructure are necessary to accurately represent the true costs of the system. (BRT refers to Bus Rapid Transit, like Metro Vancouver's B-Line.)

The next consideration is on-going operation and maintenance expense. Energy costs are isolated from the operating expenses and shown separately according to present energy costs for each mode as well as the future increase in energy costs that can be expected as non-renewable fuels such as oil become more scarce.

Using full external costs (excluding the very difficult to assess costs associated with air and water pollution caused by transport), the Toyota Prius scores best per passenger-mile, with a total cost of $1.02, followed by streetcar at $1.22. Even with negligible energy costs, the Vancouver area SkyTrain system is by far the most expensive at $2.65 per passenger-mile.

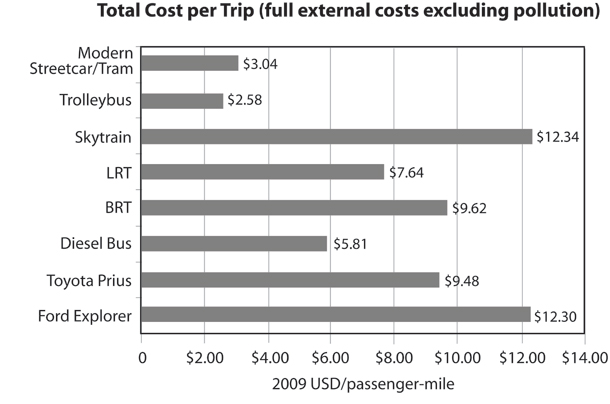

The results shown above show the cost of moving one person one mile. This kind of calculation tends to favor modes of transportation that typically travel longer distances.

But since shorter trips are, in the context of this argument, more sustainable, it is useful to also look at the cost per average trip. Low average trip distance is a marker for a more sustainable district, as it indicates that the relationship between mode and land use has been optimized. Conversely, low costs per mile gain us nothing if the relationship between mode and land use is such that all trips are unnecessarily long.

In this scenario the transportation modes encouraging land uses that support shorter trips (trolleybus and streetcar) are significantly more cost-effective than modes that facilitate more spread out land use patterns (i.e. modes designed for high speed, long distance trips).

Seeking balance

It is important to note that the benefits of streetcar city development do not come solely from the construction of a streetcar system itself. The streetcar city concept is systemic and necessarily incorporates an integrated conception of community structure and movement demands.

When applied to low-density suburban developments absent a comprehensive urban infill strategy, modern streetcars are doomed to low ridership and anemic cost recovery.

The streetcar city principle is thus about more than just the vehicle, more than just the track. It is about a balance among density, land use, connectivity, transit vehicles and the public realm.

The streetcar city concept is compatible with single-family homes yet can be served by transit. It ensures that walking will be a part of the everyday experience for most residents and provides mobility for infirm users.

It has been shown to induce substantial shifts away from auto use to transit use and can conceivably be introduced into suburban contexts. It has also been shown to dramatically increase investment in a way that neither buses nor expensive subway lines can.

It is compatible with the trend toward increasingly dispersed job sites and seems to be the form that best achieves "complete community" goals.

A realistic solution

The streetcar city principle, whether manifest with or without steel-wheeled vehicles, is a viable and amply precedented form for what must by 2050 become dramatically more sustainable urban regions. Other sustainable city concepts that presume extremely high density urban areas linked by rapid regional subway systems seem inconceivably at odds with the existing fabric of both pre-war and post-war urban landscapes, and beyond our ability to afford.

At the other extreme, assuming that some technological fix, such as the hydrogen car, will allow us to continue sprawling our cities into the infinite future seems even more delusional.

To heal our sick cities, we must recognize the physical body of the city for what it is and implement a physical therapy calibrated to its specific capacity for a healthier future.

The physical body of our regions was, and still is, the streetcar city pattern. The streetcar city principle is intended to provide both simple insight into our condition and a clear set of strategies that have proven themselves for decades.

Next Wednesday: Rule 2 - Design an interconnected street system ![]()

Read more: Transportation, Environment, Urban Planning + Architecture

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: