- The Devil's Curve: A Journey into Power and Profit at the Amazon's Edge

- D&M Publishers (2012)

Just a few years ago, 3,000 people set up a blockade and made camp along the highway artery connecting Peru's northern Amazon to the outside world, a bend known as Devil's Curve. They were Awajun natives, and they objected to the government's recent leasing bonanza of three-quarters of the jungle to foreign oil and mining interests, including those of Canada. After 57 days, soldiers were dispatched to the encampment to contend with the protesters.

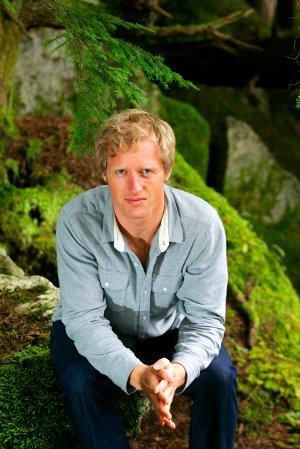

Canadian journalist Arno Kopecky saw in the deadly clash that ensued a story about globalization's furious legacies, one with clear links to home. But as he purchased his ticket to South America and packed up his notebooks, he could not have imagined the scale of adventure that would follow: days spent trailing radical politicians, gunfights in Colombia, and nights spent "hallucinating in dark huts."

His chronicle of the trip, The Devil's Curve, was recently released by D&M Publishers. The Tyee reached Kopecky, a self-described "serial vagabond," where he finally landed to put his adventures to page in Squamish, B.C., to hear more about the story.

What did you go to South America seeking to learn?

"Very broadly, I wanted to have a better idea of how distant-seeming lives are bound together. How does my lifestyle as a middle class Canadian affect the life of an Amazon Indian, say, or an urban Colombian? We're living in this fascinating time when all humanity is linking up into a single system -- some by choice, some by force -- and the workings of that system are a deep mystery to me. Cause and effect are so far apart; the environmental and social and political consequences of investing in a gold mine or filling up your gas tank or buying a t-shirt or a cut flower or a cup of coffee are basically invisible, and I wanted to make that connection.

"That's an impossibly broad goal, so I narrowed it down a little to the free trade agreements Canada had just signed with Peru and Colombia, two of the most resource-rich countries on earth. These agreements were loosely analogous to the curtain hiding the Wizard of Oz; I knew there were mortal men and women pulling the levers, putting these deals in place, and I wanted to talk to some of them about their vision, their motivations.

"And that, too, was an impossibly broad area of research, so in the end I wound up focusing on two very specific communities -- the Awajun nation of Peru's upper Amazon, and the internally displaced community living in the slums of Medellín, Colombia. Both groups were emblematic of a certain consequence of globalization; you could say they were at the opposite end of the supply chain from me. In seeking out their neighbourhoods, I was motivated by the same question that I think afflicts every traveller: What's it like over there?"

This book is investigative, but it's also a wild adventure story. What was the craziest moment of your investigation?

"Probably the gunfight in Medellín. I spent almost four months in that city, and had the great fortune to befriend a community leader named Carlos Muñoz who advocated on behalf of the internally displaced population scratching out a living on the city's margins -- well over 100,000 people who have been violently kicked off their lands in the countryside to make room for 'development.' I would often join Carlos on his forays into the slums where the displaced inevitably wound up living.

"These neighborhoods were steep, crowded and quite dangerous -- picture a warren of cinderblock huts carpeting the side of a mountain, all twisting alleyways and staircases. Very different from the tourist-friendly city centre. Medellín was Pablo Escobar's hometown, and although it's lost a lot of market share since his days this is still a pretty major administrative centre for the global cocaine trade. That means the usual turf wars, and the slums were full of well-armed teenage kids trying to become the next Escobar... very disconcerting! On one of our visits into the worst of these neighborhoods -- in fact it was to Carlos's parents house, for his family had also been displaced years ago and this was where he'd grown up -- I happened to glance out the window and saw a crew of five boys walking up a stone staircase that wound between the houses. They were maybe 16 years old, and one look was all I needed to duck back behind the window before they saw me -- a couple of them had machetes in their hands, their eyes were red, clearly not the kind of people you want to go shake hands with.

"And sure enough, a couple minutes after they walked past, we started hearing gunshots from what sounded like the roof. It might have been our roof or one of the neighbour's, but they were now shooting at someone, and pretty quick we heard those shots being returned from far away. It sounded like firecrackers, very un-Hollywood pops, but everyone in the house gathered inside and hunched under the windows -- for no one but me was it the first time something like this had happened. Carlos's mom kept cooking her chicken in the kitchen even as the firefight raged on above our heads (the house was made of cinderblocks, and was therefore bullet-proof), and you'll have to read the book to find out how it ended, but apparently I survived."

One of your first Peruvian sources tells you that a Canadian mining company was at the centre of the Devil's Curve clash. How did that story unfold?

"The book's inciting event is a showdown between the Peruvian army and a group of Awajun Indians who had set up a road block on a stretch of highway called the Devil's Curve, which links Peru's Amazon to the Pacific port towns. The Awajun blockade was actually just one link in an Amazon-wide protest involving over 60 rainforest tribes, all furious that 75 per cent of the Peruvian Amazon (an area the size of France) had been leased to foreign resource companies without consulting the people who live there...blockades and strike actions were coordinated all throughout the rainforest, but the Awajun's closure of the Devil's Curve was the most costly blockade from the government's perspective, and on June 5, 2009, the army went in and opened fire on 3,000 unarmed Awajun protesters.

"That day is more or less etched into Peru's national consciousness now. I went to the Devil's Curve, and then to the jungle beyond in the hopes of meeting some of the Awajun who were involved in the protest. I had no idea at the time which, if any, companies they had specific grievances against, let alone what nationality such companies might be. But it turned out that there was indeed a company operating on Awajun territory, and if it hadn't been there, they probably wouldn't have been motivated to travel hundreds of kilometres from their jungle villages to camp for two months in the baking sun, risking the assault that eventually did come. That company wasn't only Canadian; it was, and is, based in Vancouver, and it's called Dorato Resources.

"Dorato is a gold mining outfit that gained exploration rights to a steep mountain range that is very full of gold. It's also a sacred range to the Awajun for a number of reasons, not least of them being that this is where their rivers and their drinking water comes from -- some 40,000 people depend on that watershed to stay pure, and they are reasonably concerned that gold mining might have some deleterious effects.

"As I got deeper into Awajun territory, the story of how Dorato got the rights to that mountain range came into focus, along with the Awajun reaction -- it's a rather complex tale, which is one of the reasons it was so nice to have an entire book in which to tell it."

Has there been any response from companies working in Peru to your book?

"The companies themselves stayed out of the clash at Devil's Curve, which is often the case in these kinds of situations. Sometimes you'll see corporate security forces doing bad things, but what's interesting about these free trade agreements and the linking of corporate/state power generally is the way state security apparatus are engaged to do the dirty work. That way, the company can say 'We haven't done anything wrong, we haven't hurt anyone or kicked anyone off their land.' No they haven't -- the government's already done it for them, in order to create a positive investment climate."

You met an Awajun leader named Joel Shimpukat who wrote a letter to the Assembly of First Nations Chief Shawn Atleo, in Canada, requesting a conversation after the showdown. Why would he reach out to Atleo?

"Joel is an Awajun leader who was one of the chief organizers of the Devil's Curve blockade -- a lot of logistics go into keeping 3,000 people watered and fed for two months. After the conflagration, in which 25 soldiers were killed, the government issued an arrest warrant against him for his role in the protest, charging him with sedition, and so Joel fled back to his jungle community, far enough from any roads or police stations that the law wouldn't come after him. I met Joel through a chain of phonecalls, handshakes and introductions that started in Lima and led all the way to his village, Numpatkaim, three hours down the river from the end of the road.

"Joel took me in, much as Carlos Muñoz did in Medellín, and showed me around his part of the world, introduced me to his community, shared his life and his stories. He was incredibly generous and kind, but he was also quite exhausted and burned out from the stress of trying to raise a family, lead a protest movement, and deal with his arrest warrant. I told him some stories of how Canada's indigenous cultures were facing many of the same problems, and he took a great interest in these, asking me if there was a leader he might communicate with to arrange a meeting. I've never met Shawn Atleo, but I told Joel that he was the National Chief, and Joel was overcome by a moment of passion and immediately wrote a letter to Mr. Atleo, basically suggesting that Canada's indigenous societies and Peru's might benefit from mutual association, given their common concerns. I promised I'd do my best to deliver that letter, and when I got home I sent it through the channels I had, but I suspect Mr. Atleo has his hands full at the moment. For good measure, I re-printed it in the book.

"At any rate, Joel's letter may not have found its mark, but indigenous networks from across the Americas and beyond are indeed starting to form strong connections, and... that's another story."

In Canada there are aboriginal groups fighting to defend land from intensive resource development. What kind of parallels, if any, would you draw?

"The equation that if you're against one specific development you must be against them all -- this is the logic I saw deployed by the governments of Peru and Colombia to advance the interests of foreign investors. It was a very black-and-white, with-us-or-against us rhetoric that basically criminalized dissent and refused to consider a slower, better regulated, more nuanced approach to development; as with Canada, the Peruvians who actually had to live with the consequences of unregulated resource extraction tended to be the indigenous cultures on whose turf the drills and explosions and chemicals were inflicted.

"So now we have a Harper administration, led by our Prime Minister and Natural Resources Minister Joe Oliver, accusing anyone who speaks out against the Northern Gateway project of being either against all work and jobs, or of being funded by foreign radicals, or both. This is precisely the argument that president Garcia used in Peru, and it is no less absurd. Our First Nations, like Peru's, are interested in all kinds of developments projects, just not the Northern Gateway; and the proportion of foreign funds backing Enbridge Inc. certainly dwarf those of any First Nation."

In the book's preface you quote Peruvian novelist and Nobel Laureate Mario Vargas Llosa as years ago writing: "It's not true that rich countries are rich because other countries are poor." How does your book engage with that statement?

"I aimed to provide some caveats to Llosa's statement. I don't think rich countries get all their money by sucking it from poor victims, and I don't think poor countries can blame all their woes on wealthy nations run by corporations -- the world has come a long way since the Conquista. But there remains a parasitic aspect to some of our dealings with countries like Peru and Colombia, which I think is worth exposing."

Reflecting on the final product, The Devil's Curve, what story do you think you're ultimately telling?

"For me the lovely thing about writing a book was that I had 90,000 words to tell a story. You can really go down some fun rabbit holes with that kind of time. Brevity has never been a strength of mine. But I'm okay with that, because good story relies on characters, on human development, and it takes more than 500 words to draw a human portrait that evolves along an arc. Ultimately, I think -- I hope -- that I've told a few human stories, everyman stories about struggle and hope and betrayal and loss, set against a political backdrop of globalization."

We heard you have another book cookin'. What can you tell us about it?

"Yep! I'm working on a travelogue about the Northern Gateway oil tanker routes -- I just spent an unforgettable three months aboard a sailboat between Bella Bella and Kitimat, getting to know a part of the world that is truly going to test my vocabulary.

"The book will be called The Oil Man and the Sea, and in many ways it's a Canadian sequel to The Devil's Curve. This time, it's our own indigenous communities (along with some notable allies) who are fending off a very hungry, very powerful, but ultimately very bumbling corporate assault.

"It's also about learning how to sail." ![]()

Read more: Indigenous, Rights + Justice, Labour + Industry

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: