If we build it, they will come. Or will they? And does it matter if they don't? What is the importance of having a public square in the 21st century city, whose citizens are more likely to commune electronically, in virtual space?

Vancouver's planning and design community has long bemoaned the lack of a major public open space in the centre of the city, like those great squares that so many other cities are identified with. Meanwhile, critics have noted the city's eccentric emphasis on public life at the periphery. Vancouver has always had more intense public spaces at its edges than at the centre: Centrifugal City.

It seems that Vancouver's true public spaces are its beachfront parks, plazas, walkways and associated strands. Meanwhile, the centre seems curiously absent of such a social condenser, where the citizens of this city can come together to celebrate, commiserate or demonstrate as they do in other cities. The centre -- to paraphrase Yeats -- does not hold.

Dream city?

As I noted in the closing chapter of Dream City: "If it can be said that Vancouver has a curiously distorted public space culture, as represented by the architecture and uses of its public spaces, then it must also be said that, in its own peculiar way, and with barely a nod to traditional Western notions of formal public space, this culture is as vibrant and alive as any. For proof, if such is needed, you need only go down to the beach. That's what everyone else does."

Which makes the city centre an easy target for many cultural critics, and unsurprisingly it is this "underutilized" centre that was the focus of many of the submissions in the recently concluded Where's The Square design ideas competition for a major new square in Vancouver.

Organised by the grassroots Vancouver Public Space Network (VPSN), an affiliation of several hundred people with an abiding interest in the public realm of their city, the competition attracted some 54 submissions from around the world, by professional architects, landscape architects, planners, students and lay people. (See sidebar for more on the winners and how they were chosen).

The what of 'Where’s the Square'?

The Where's The Square design competition brief proposed that public squares form the heart of great cities around the world, and they are the spatial realization of democratic principles. And it asked contestants to answer two simple questions: where might such a public square be located in Vancouver, and what might it look like?

When, on April 27, organisers revealed 13 short-listed submissions in the running for the People's Choice Award, to be determined by a popular vote, at least one speaker -- writer Matt Hern -- questioned the very premise of the competition. Hern asserted that what Vancouver really lacks is unplanned open spaces that act as a spontaneous public commons in which unprogrammed, unpredictable and uncontrolled activities can take place. Such spaces need not be grandly designed or large -- indeed, this is often the kiss of death for spontaneous activity. His argument was essentially for less planning and design, not more. It is a powerful point to consider in a city as rapidly gentrifying as Vancouver.

For me, who helped judge the Jury Selection Award, that idea was among many that made the Where's The Square competition a success. The selection process sparked meditations on public space in the contemporary city. Allow me to share a few of my own.

Centre versus edge

Many contestants focused, unsurprisingly, on the most well-known yet largely dysfunctional central space in the city: Robson Square, and the adjacent open space on the north side of the Vancouver Art Gallery, long orphaned with the closing of the former main entry to the Provincial Courthouse on that side. This precinct seemed to be the most charged area of the city centre for many, and three or four strong finalist contenders emerged (one of which won the People's Choice Award). If you accept that a major public space ought to be located at the epicentre of the city, then Robson Square seems to be the conventionally agreed locus.

Another group of strong submissions investigated the case for locating such a space at the edge of the city, in various waterfront locations. Specifically, several schemes investigated the historical waterfront origins of the city in and near Gastown overlooking Burrard Inlet, and yet another compelling scheme faced onto English Bay at the foot of Denman and Davie streets. These are powerful, charged sites, and the designs had many compelling ideas conveyed with often powerful graphics.

Centre versus Edge; inward-focused versus outward-looking; Centripetal City versus Centrifugal City. On the jury, a rich discussion ensued, with advocates emerging for both propositions.

But ultimately, the jury chose to land in neither camp. In an old design ideas competition tradition, the jury went back and pulled a previously rejected project out of the Also Ran pile that immediately captured the imagination of all jury members, and which seemed to go to the heart of the matter and answer it in a thought-provoking, provocative yet lyrical way.

Banding together

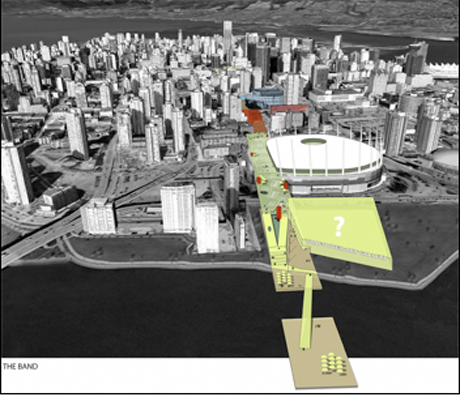

The Band (see it here) by Mark Ashby Architecture & Greenskins Lab (Mark Ashby, Kevin Kong, Isabel Kunigk and Daniel Roehr), proposed a linear public space stretching from Robson Street at Library Square, past the CBC Headquarters, slicing through a chunk of BC Place Stadium, then continuing down over Expo Boulevard to engage with the proposed site for the new Vancouver Art Gallery, intersecting with the existing waterfront walkway, and finally ending in a floating public platform in False Creek. As the submission text put it: "To create a square specific to Vancouver, the traditional square is 'unbundled' and reassembled in a linear space edged with public institutions. The combined public square is programmed sequentially by each institution in turn..."

The Band, in one grand, deceptively simple gesture, unites both Centre and Edge. As a kind of transect across the grain of the city, the Band at once engages and unifies a series of major public institutions, provides a riposte to the profound interiority of BC Place Stadium by lancing that bloated boil, and interrupts the sacrosanct homogeneity of the city's waterfront walkway system. It offers a rich diversity of uses along its length, with sequential zones of the Band representing the themes of urban agriculture, media, play (sports) and culture. Oh, and it is beautifully drawn.

Existing buildings are allowed to "step" on the Band, which creates interesting programmatic tensions between inside and outside spaces. Most compellingly for the jury, the Band concourse cuts through the monolithic superstructure of BC Place, providing a public space for passing pedestrians to enjoy a free peek into the stadium. Or is it the pedestrians who are being gazed upon by the stadium goers? What, precisely, is public and what private? And is the Band in fact a square, or a route? It is exactly this kind of critical ambiguity that drew the jury to this submission in the first place: it is both/and, rather than either/or. And perhaps that is the essence of Vancouver. We are not, after all, a European city, but something more hybrid, and the selected design solution reflects this ambivalence.

Size and scale

Another key issue was the question of how big a space needs to be, before it gets too big? Take the newly completed plaza at the recently opened Vancouver Convention Centre overlooking Burrard Inlet. It is vast, and while elegantly designed, it is hard to imagine ever being filled and charged with urban vitality. On the other hand, the far more modestly scaled square in back of the Granville Island Public Market is tiny by comparison, yet is often filled with people and feels so much more animated. Getting the scale right is important: if big is good, bigger is not always better. You can have too much of a good thing! Several shortlisted squares were simply too large.

Related to this is the critical importance of spatial containment and the type of uses in the buildings that frame a square. Several projects failed to provide compelling scenarios for the surrounding uses, or did not address spatial containment at all. The Band, however, not only engaged multiple existing public uses along its length, but by re-orientating these facilities, thereby gave them new meaning.

Who's watching?

In a post 9/11 world, and with the rapid approach of the 2010 Olympic Winter Games and its attendant security blanket about to descend on Vancouver, the issue of public surveillance was an important concern in the jury discussion. It was noted that the Robson Square precinct was probably the most heavily monitored part of the city, and that for some jury members, this in and of itself precluded this precinct's suitability as the city's major public open space, especially if this meant that certain sectors of society would not feel welcome in such a space.

What constitutes real public accessibility? The jury readily agreed that in order to be truly accessible as the city's major public gathering space, the definition of "accessible" must include social and economic accessibility: all sorts of people, from the full spectrum of our society, ought to feel comfortable (or at least not unwelcome) entering into and participating in the public life of such a space. This meant that some otherwise compelling submissions were rejected because they were too disconnected from the fabric of the city or had restricted physical connections, and therefore access was all too easily controllable.

As governments move toward ever more intrusive and pervading public surveillance, this issue will continue to haunt any discussion about public space in the contemporary city.

Hip to be square

So, what might we learn from the Where's the Square ideas competition? Well, among many lessons, one stood out very clearly for the jury: Vancouver needs more design competitions. We should be fostering a design competition culture as a critical strategy in the pursuit of design excellence. Many other societies do this, especially in Europe, resulting in much higher standards of creative design and a raised awareness of the value of design in our lives.

Vancouver, this stripling adolescent of a city languidly sprawled out on its rainforest peninsula at the edge of the continent, with its feet in the sand and sentimental regard of the surrounding sea and mountain panorama, has a lot to learn from such cities. Where's the Square is an excellent start.

Related Tyee stories:

- Be square, Vancouver

- Is Your City Boring? Make It Wild

Two BC architects want to transform cities into literal urban jungles. - Welcome to Vancouver 2.0 'FormShift' winners challenge city to be denser, greener, more exciting.

Read more: Urban Planning + Architecture

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: