When the government of British Columbia stated in fall of 2001 that it intended to force people off welfare after a certain amount of time, it was announcing changes that were unprecedented in Canada.

Changes that never happened.

Before the time limits could take effect in B.C., in early 2004, the provincial government announced regulatory amendments that effectively ended the experiment.

So who was responsible for the reversal? Whose opposing voice was heard loudest? How did a policy launched with such government fanfare end up scuttled so quickly?

Our search for answers took us through more than 1000 pages of internal government documents obtained through a freedom of information (FOI) request as well as numerous public documents and media reports, and resulted in a report titled The Rise and Fall of Welfare Time Limits in British Columbia, published last month.

The story that emerges offers insight into the politics of policy-making, and some key players in the drama may surprise.

Setting a time limit to purge rolls

In January 2002, the recently elected Liberal government announced a broad program of regressive welfare measures whose goal was to cut the income assistance budget and caseload by 30 per cent. Under the new rules, welfare was to be limited to 24 months within a 60-month period (or two out of five years). Single recipients and couples without children would be denied benefits altogether for the remainder of the 60-month period, while recipients with children would have their benefits reduced by between $100 and $200 per month.

While simple in concept, the rule was complex in practice. The ministry had to not only track the different classes of individuals who were subject to or exempt from time limits, they also had to track the months during which recipients ordinarily subject to time limits would be exempt, for reasons such as a temporary inability to work. The legislation creating time-limited welfare was made effective April 1, 2002. Thus, the first recipients subject to time limits would have their benefits cut off in April of 2004.

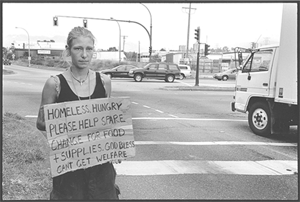

The first opposition to time limits arose amongst groups concerned for people in poverty, including front-line community organizations, anti-poverty groups, people in poverty themselves, progressive policy analysts and academics and public interest lawyers. These groups voiced their opposition when the government first made public its intention to legislate time limits, and also organized against time limits in the spring of 2002 when time limits were translated from a policy proposal into legislation. However, these efforts led to little public attention or support.

Resistance within ministry

The first effective opposition to time limited welfare arose after the legislation had taken effect and, interestingly, originated within the ministry charged with implementing time limits. While the civil-society organizations were motivated by concern for the well-being of those in poverty facing time limits, the motivations of ministry staff were more complex.

The internal documents obtained through the FOI request reveal that ministry staff identified and brought to the attention of their leadership that time limits would apply to recipients who could not be expected to find or maintain employment. Time limits would deny benefits to those who in the ministry's own assessment should receive assistance, and therefore were contrary to the mandate of the ministry.

Ministry staff also alerted their leaders to the fact that the government could face "negative public reaction" when time limits took effect. As a result of this opposition to time limits within the ministry, in the spring of 2003 the government began to adopt numerous exemptions to time limits for several classes of recipients.

The goal of ministry staff was not to challenge time limits in principle, but to exempt from their application recipients who in their view could not support themselves in paid work.

Activism bears fruit

Meanwhile, by the summer of 2003, the groups opposed to time limits from the outset were successful in bringing time-limited welfare to the attention of mainstream society. The number of recipients facing time-limit sanctions was unknown, but leaked government documents indicated that it could be upwards of 19,000 people.

By the fall of 2003, opposition to time limits was manifested in resolutions passed by municipal councils, including Vancouver and Victoria city councils, resolutions of school boards, and statements from various faith communities.

Earlier the B.C. Association of Social Workers had issued a statement opposing the time-limits legislation, and the opposition NDP and unions also spoke against time limits to welfare.

The motivations of these groups were likely diverse, but the public record indicates that a primary concern of the groups representing mainstream society was the prospect of a dramatic increase in the number of homeless people in April 2004, with all the community and social problems that would ensue.

Politics hot to manage

In the fall of 2003, internal documents reveal, there was also a significant shift in regard to time limits within the government. The focus shifted from ministry staff concerned with the mandate of the ministry to the politics of managing an issue on which the government was facing significant and increasing public opposition.

At this stage, the debate galvanized around the question of the number of recipients facing time limits. The government refused to answer this question. This secrecy led to the media itself becoming a force of pressure upon the government, as the credibility of the government crumbled on its refusal to answer simple questions that were clearly in the public interest.

Government back pedals

On Feb. 6, 2004, the government capitulated and introduced a 25th exemption to time limits. It exempted recipients who were complying with their employment plans, effectively making the policy redundant, as it was already the case that people found to be non-compliant with their employment plans could be cut-off.

The result was that, according to ministry projections, the number of recipients facing time limit sanctions in 2004 and 2005 would fall dramatically from 6,777 to 339. In fact, information obtained through the FOI request indicates that the actual number affected in this time period was 31.

It was a reluctant capitulation, not motivated by humanitarian concern for people in poverty, but rather by pure political expediency.

The downfall of welfare time limits is noteworthy because it is one of the very few successes in defeating the regressive welfare reforms that have been implemented in Canada over the past decade.

It appears that this success is primarily attributable to the pressure exerted by mainstream society through its representatives such municipal councils, and that the primary motivation was the perceived harm to communities that would result from a large increase in the number of people who are homeless.

However, the success of this mainstream opposition depended in part on the organizing and work of smaller groups involved in anti-poverty work. While the opposition from these groups was loosely organized, it was effective in providing accurate and timely information and analysis, which articulated the concerns of mainstream organizations. These smaller groups were acting as a catalyst to bring divergent groups such as city councils, school boards and faith communities together to voice their shared opposition to time limits to welfare.

Rolls slashed through other means

In retrospect, the failure of the implementation of time-limited welfare did not significantly shift the Liberal government's punitive welfare reform agenda. The government's target of a 30 per cent reduction in the welfare budget and caseloads was achieved through other methods, particularly the new rule that required two years of financial independence in order to be eligible for welfare, and a new required wait of three weeks before a person could apply for benefits. In this sense, the resistance to welfare time-limits was only a limited and partial victory.

However, the government's capitulation on time limits provides a compelling rationale to reconsider and rescind the requirements for two years of financial independence and the three-week wait. These eligibility requirements, in a manner similar to time limits, make income assistance benefits conditional on arbitrary rules and time periods. They should be rescinded by the government for the same reason that time limits were rejected, which is that they have imposed tremendous hardship on citizens through the denial of assistance to those in need and have contributed to the current crisis of homelessness.

Related Tyee stories:

- A Welfare 'Savings' Boomerang

Campbell's cuts ended up costing BC taxpayers billions, studies suggest. - 'Welfare to Work' Didn't Work

BC Libs sat on own report showing no real gains. - Facebook Used by Officials to Spy on Welfare Clients

BC officers cruise social sites for fraud evidence. - How BC Trimmed 107,000 People from Welfare Rolls

Some got jobs. Red tape, death likely knocked out far more.

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: