When the electoral boundaries commission released its report last week, the news seemed obvious: it looked like your typical city vs. country story.

After years of urban growth and shrinking populations, the province's northern interior would be stripped of three seats. The bulk of additions to an expanded 81-seat legislature would be bestowed upon the booming Lower Mainland, the engine driving B.C.'s population growth.

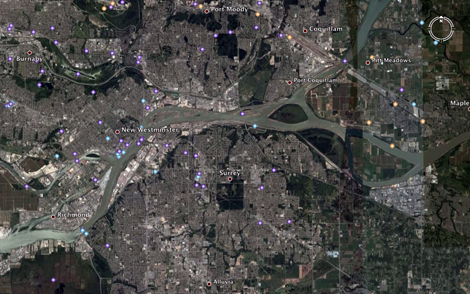

But the bigger story, in the long run, may be where those Lower Mainland seats end up. Under the report's recommendations, only one of the four new urban seats would be tacked onto the city of Vancouver. The other three are to be spread among the city's ballooning suburbs and exurbs: Surrey, the Fraser Valley and the Tri-Cities area would each earn an additional member.

Suburbs are driving population growth across Canada. Nowhere more so than in B.C. And as suburban populations blossom and electoral maps are redrawn, the politics of this province -- and this country -- are changing.

Suburbanites vote conservative

How that change reshapes B.C. is a story for another day; if not during the 2009 election, then certainly in 2013. It is, however, already an issue elsewhere in the nation.

Suburban support fuelled the growth of Mario Dumont's ADQ party in this year's Quebec provincial election. The suburbs also provided the core of Mike Harris's support during the conservative revolution that swept Ontario in the 1990s. Federally, meanwhile, Stephen Harper made waves in 2006 when he won a minority government without a single seat in the urban cores of Canada's three largest cities.

The common thread among Dumont, Harris and Harper is that they're all Conservatives. And not old school Blue Tory Progressive Conservatives either. It's no coincidence.

A small but growing body of academic literature -- much of it produced by youngish urban geographer Alan Walks -- suggests suburban and urban Canadians vote in significantly different ways. Put simply, suburbanites are more likely to vote conservative than are their urban neighbours. And as the suburbs grow, so too will the conservative clout of their residents.

When I spoke to Walks on the phone from his lab at the University of Toronto's Centre for Urban and Community Studies, he had no problem imagining the day when a conservative party could win a majority government in Canada without any support whatsoever in inner cities.

"It could happen now," he said. "Oh yeah. Particularly because a lot of rural areas and areas in the West will vote Conservative no matter what."

Cities to lose electoral power

It may soon be possible for a party to take a majority of Canada's Parliament with only suburban seats.

"Depending on how the riding boundaries are drawn, I definitely think it's possible," Walks said. "That's what happened in the U.S. I think about 1990 or so, from that point on, more than 50 per cent of the population lived in the suburbs."

What that means in practical terms is pretty clear, according to Walks.

"It portends less of a voice for the inner city," he said. "We're not likely to see any government step into the breach and meet the city's demands for infrastructure maintenance."

Other issues that get labelled as city concerns could suffer as well. "When you live in inner cities, you see homelessness, you see declines in public transit and other public infrastructure on a daily basis. And you think 'this isn't right,'" Walks said. "But in the suburbs, where you don't see these kinds of things, you're more likely to tune them out. And if you do see them, you think, this isn't a suburban problem, it's an inner city problem, I don't really need to worry about it."

Mature suburbs may diversify

The implications for social policy may not be so obvious.

Consider supervised injection. While some might see the Tories waffling on the trial as an example of them throwing a big city issue under the bus to appease suburban supporters, Walks isn't so sure.

"My guess is that some people in the suburbs might be worried about poverty infiltrating their own neighbourhoods, and they might even want to keep it in Vancouver," he said. "So they might see this as a way of keeping it there."

There's also a danger in over generalizing the suburbs. Yes, overall, right now, they do tend to vote conservative. But that could change, or at least ebb, in the future.

As city centres become more expensive, they're going to become less of an option for many people, Walks said. That might serve to moderate the suburban vote.

"In the Vancouver region, that may very well be," Walks said. "Especially as Vancouver gets so expensive and pushes those who can't afford to live there to the edges, you might start seeing a reversal."

Immigration is another big issue. "The Mike Harris government, here in Ontario, removed much of the regulations on developing green field sites and in turn it led to this huge building boom at the edges," Walks said. "So you might think it would have been this great constituency for the Harris government. But no, it's not true. Most of those moving into these new developments are immigrants who are more likely to vote for the Liberal party. So that cancelled out whatever benefits the expansion would have had for [the Conservatives]."

Suburbs vs. everyone else?

Canadian politics have traditionally been viewed as the product of conflict among various cleavages: French vs. English; East vs. West; urban vs. rural. But with the nation fast suburbanizing, the defining cleavage for the next generation of Canadians may well be city vs. suburb.

Of course, as the shrinking hinterland support recommended by the B.C. electoral boundary commission suggests, it's not just city dwellers who may lose out to the coming suburban tide.

"Things aren't likely to get better for the cities," Walks warned. "But they're not likely to get better for rural areas either."

Related Tyee stories:

- For Tories, Cities Aren't Sexy

Harcourt report too hot to handle, maybe for Grits, too. - Quebec: Angry, Torn

Pinched voters vent against rich, poor, immigrants and the political class. - The Myth of Dense Vancouver

Stats show city isn't countering flight to suburbs.

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: