Consider where we live.

At a time when nation states are fraying, imperilled by appeals to hard-hearted nativism and isolationism, we have the remarkable good fortune to live in a place well-equipped to not just survive the turmoil besetting the globe — but to lead in adapting to the existential threat of climate change.

If you live on the Left Coast, think of yourself as an inhabitant of Salmon Nation. You share this extraordinary place with more than 30 million other residents, from northern California to southeast Alaska. You share where you live with the plants and animals and life support systems of which you are a part and upon which you wholly depend: clean air to breathe, water to drink, productive soil, and a relatively benign, albeit changing climate.

And salmon? From the headwaters of our great rivers all the way to the coast and out into the Pacific Ocean, salmon are the best biological indicator of healthy communities. They are a pulse of natural life and sustenance in our coastal temperate rainforest bioregion, charismatic, iconic species that give shape to what we might think of as our nature state. They are totems of our most ancient cultures, and of the new ways of living that we so desperately need.

I’ve lived and worked in Salmon Nation since 1981. I first worked as an editor and reporter for the Vancouver Sun, then as a documentary reporter for CBC Television, and for almost 20 years ran Ecotrust in Canada, the U.S. and Australia. These past few years I’ve been a columnist for The Tyee. For nearly four decades I’ve been telling and retelling the story, and the stories, of Salmon Nation.

This year, I’ve been honoured to be appointed the inaugural Dan and Priscilla Bernard Wieden Endowment Salmon Nation Storytelling Fellow. What that means is that I’ve been given free rein to write about the places I know and love, and about extraordinary people who help their communities thrive in our shared bioregion.

I’ve written my fair share of doom and gloom stories, mostly about our so-called “natural” resources, and our abject and spendthrift abuse of our collective natural capital. As despairing as these stories can sometimes be, usually, at the heart of a story are people whose ingenuity and capacity for adaptation is both extraordinary, and extraordinarily hopeful. In fact, the only inexhaustible natural resource we have is our ingenuity — and that’s what I want to write about as a Salmon Nation Storytelling Fellow.

I intend not just to write about where we live, but how we live, and how we can all work to leave where we live better than we found it. To start with, here’s a story from my alma mater, if you will.

Welcome to the Redd

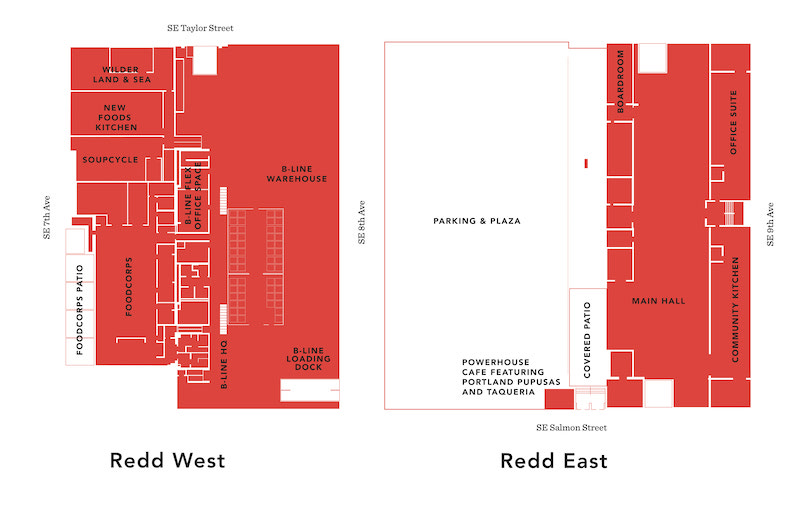

A redd, as any self-respecting fisherman knows, is a nest dug in gravel by a salmon on a river’s spawning grounds. The Redd, aptly named given its location on Salmon Street in Portland’s Central Eastside, is likewise a breeding ground for whole new ways of thinking about food — and for filling a gap in supply chains that has bedevilled decades of efforts to build reliable and scalable markets for sustainable agriculture.

On March 2, Ecotrust opens the Redd on Salmon Street to the public. To be more precise, it opens the Redd East, a spectacular remodelling of a century-old industrial foundry and machine shop that’s been rebuilt to tell a whole new, hopeful story about how it’s possible “to really run a regional food system in the heart of a big city,” says Emma Sharer, operations manager for the Redd.

Amidst its neighbourhood of grey concrete and warehouses, the Redd stands out, an enormous mailbox-red barn covering half a city block.

Drenched in natural light from tall clerestory windows, powered by a solar array, its walls paneled with hemlock sourced from a certified sustainable forestry operation and cedar gifted by the Coquille Indian Tribe, the Redd has 16,000 square feet of space allowing gatherings of up to 670 people (2,000 if you count the outdoor plaza), served by a fully equipped training and demonstration kitchen — a meeting, working, celebration and teaching space, with food taking centre stage.

Amanda Oborne, vice-president of food and farms at Ecotrust, says “the food economy we want doesn’t exist yet” and the Redd campus, as she calls it, is designed to foster “connections and collaborations of businesses doing work together to really iterate and define what this new food economy could be.”

The idea of the Redd came from answers to questions posed by Oborne and her team in a study of Oregon’s food system — Oregon Food Infrastructure Gap Analysis published in 2015. (It echoes in many ways a 2010 award-winning Tyee series on how to strengthen local food economies in B.C. and Ontario.)

Portland “has a thriving US $4.3-billion food sector, and an international reputation as a hub of creative ‘farm-to-table’ innovation,” the analysis found. But getting farm products to those tables isn’t as easy.

‘Ag of the middle’

In 2014, Oborne and other researchers had fanned out across Oregon “visiting cold storage facilities and slaughterhouses and distribution centres and farms and ranches and the whole gamut of food system stakeholders, trying to understand what the barriers were preventing local food systems from flourishing and growing up beyond farmers markets or CSA (community supported agriculture),” she recalls.

What they found, according to the report, is that “food aggregation, processing, and distribution infrastructure is not readily or affordably accessible by Oregon’s small and midscale, differentiated farmers, ranchers, and artisans, and that this lack of access is inhibiting the growth and development of a robust regional food economy.”

But so what? After all, the road to non-profit ruin is paved with earnest gap analyses — heavy on data, long on problems, short on solutions. Enter Spencer Beebe, founder and currently executive chair of Ecotrust. Right about the time Oborne’s report was bemoaning the lack of infrastructure for what Ecotrust and others call “Ag of the Middle,” Beebe was in the middle of buying two full city blocks in Portland, each with a warehouse on it. Redd East has since been developed as an eye-catching showcase for Ecotrust’s food and farms program, but what really sets it apart from other spaces for brainstorming big ideas is that it is harnessed to a serious workhorse for Ag of the Middle, stabled across the street in the Redd West.

Beebe imagined these buildings would comprise “a campus hub for innovation in bioregional food and farm systems … a tiny fractal of Salmon Nation as a living, breathing, co-evolving and iterative global shift from an industrial to a natural model of development.” So Ecotrust bought the two blocks, and has sunk US $25 million, including acquisition costs, into building “a marketplace for the goods, services and ideas of a conservation economy,” as Beebe puts it.

By contrast to Redd East, Redd West is unglamorous, a kind of engine room for connecting farmers to markets, “essentially a box of infrastructure going from cold storage to dry pallet storage to kitchen production space, and offices, a delivery team,” Sharer says. “What’s really magical about it is that as a food company you can not only produce your product here, but store it and distribute it all from the same location. In our current food system that really doesn’t (otherwise) exist.”

Typically, a rancher or fisherman or farmer or orchardist or other rural food producer — and this is true pretty much any place at the seam between lands where food is produced, and urban centers where it’s mostly consumed — is either selling into commodity markets, or confronts enormous barriers in getting specialized products into supermarkets, grocery stores, restaurants, schools, hospitals, nursing homes and corporate cafeterias.

“Last-mile warehousing and logistics seems to be a particular overarching pain point, especially for rural producers,” the gap analysis says. “Many describe the difficulty coordinating the myriad details required to manage multiple partners from afar, necessitating frequent trips to town, and time spent while there coordinating operations rather than meeting with current and potential customers to grow their businesses.”

Redd West addresses that problem head on. “Instead of business owners using their Subarus to make deliveries to the groceries and restaurants and markets around town, we have a central space for distribution and a mechanism that brings the product to market,” says Jeanne Kubal, vice-president of events and engagement at Ecotrust.

Redd West was the first of the two campus blocks to be developed. It opened in 2016 and already hosts more than 170 food businesses, “that are either distributing, housing, warehousing or creating their product in that space,” Kubal says.

One of the keys is cold storage — 2,000 square feet of it, absolutely critical for fish and meat producers, and rare as hen’s teeth in urban areas unless you’re a large commodity operator. There are commissary kitchens, and it’s not unusual to see a sole operator labelling jars, packing boxes, or just using desk space instead of making calls from the seat of their car or truck.

It’s also not unusual to see B-Line trikes heading out across Portland packed with food orders from restaurants and other food retailers. B-Line an anchor tenant of Redd West, manages 15,000 square feet of warehouse space, co-working office space, and a fleet of seven cargo trikes and a truck that deliver upwards of $200,000 of product value a month into the Portland food ecosystem. (Vancouver B.C.’s SPUD also uses trikes, although its deliveries are to food consumers. Shift Delivery trikes can also be seen on Vancouver streets.) B-Line founder Franklin Jones estimates that “in vehicle trips avoided, we’ve taken about 30,000 miles out of travel out of the system.” He has about 150 clients, including one of the stars of northwest food retailing, New Seasons Market.

New Seasons, which operates 18 stores in the Portland areas, boasts that it “brings delicious, healthy food from local farmers, producers, ranchers and fishermen to our communities.” But doing that efficiently turned out to be tricky.

'Not about affluent foodies'

“We started working with a lot of small local producers, which created a situation where we had vendors driving all over the city to deliver their product to our stores,” says Chris Tjersland, New Seasons’ partner brand development manager. It was a bad use of vendors’ time, but also it was disruptive for the stores — small producers parking in back, taking up staff time, creating safety issues, often for relatively small transactions.

Now, 70 New Seasons vendors are one-stop dropping their products at Redd West, where they are sorted onto carts and rolled onto trikes or onto B-Line’s truck (it serves stores outside the urban core), and are rolled off at the other end. “It’s created a lot of efficiencies for us,” Tjersland says.

And “it’s a big win” for vendors, he says. “When they look at their cost structure when they’re starting their company, they never really think about the cost of delivery. They think, ‘Well, you know, I can put the product in my car; I can drive out to the store and drop it off. They don’t think about the cost in their time, the wear and tear on their vehicle. I’ve had vendors that, it can take them a full day or two full days just to deliver to our stores. We’ve now freed up their time to do other things.”

Redd West operates at about break-even, Beebe says. Ecotrust hopes to turn a profit in both Redd buildings. In its first investment in Portland real estate — the Natural Capital Centre in the fancier Pearl District (in Vancouver, think Yaletown) — Ecotrust discovered there was a premium to be had on good events space. The Redd East will take that to a whole new level.

“We’re absolutely trying to return a profit in this space,” Kubal says. And while they’re at it, privilege businesses that are minority and women-owned in supply chains for large-scale food festivals and other events they will stage in Redd East. But mostly — call it big box retale — to leverage a huge space to tell very different stories about food: where it comes from, where it’s going, and how to be part of changing the system for the better.

“This isn’t about tiny artisanal craft production sold to affluent foodies,” says Oborne. “This is about changing the nature of food security in our region and changing the nature of the regional food economy for the producers in our region.” It’s also, she says, about “planting the seeds for climate resilience in the region. A lot of the other work we are doing with farmers and ranchers has to do with (them) adapting their production practices… (and) mitigating the effects of climate change by virtue of the way we manage and steward the land and the rivers as well.” And beyond Portland? Every productive salmon stream in Salmon Nation has redds, but surely not every town can have a Redd.

Vancouver’s missing hub

A decade or so ago, Vancouver B.C. proposed a New City Market that at the time was predicted to be “the crown jewel” of the city’s local food system. Even with the promise of free city land, the project never materialized, “leaving behind a murky trail of heavy spending and lack of accountability,” according to one account. It’s still a sorely needed piece of rural-urban connectivity that’s missing from the city.

Now the Redd is up and running, Oborne hopes it will inspire imitators. Beebe, borrowing from urbanist Jane Jacobs, says the trick is always it to “’release the energy of local residents.’ Where was that energy (in Portland)? Food. The result? Another experiment in building resilient institutions. We hope.” Another thread in the fabric that helps to counter our growing urban-rural divide.

Non-profit mission statements, not to mention funding proposals, are littered with promises to demonstrate scale, diversity, impact, resilience, adaptation, and inspiration. Pilot projects launch every day, often on a wing and a promise, but it’s rare to see one land. Beebe, a veteran bush pilot, knows there’s an old saying among airplane pilots, “Takeoffs are optional, landings are mandatory.”

He took that to heart at the Redd — and found just enough runway in Southeast Portland. The hope is there are plenty of other places to land in Salmon Nation. ![]()

Read more: Food

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: