Beneath the surface of the sea along B.C.'s coast lies a city of living, growing glass. Towering up to 20 metres above the murky darkness of the sea floor, glass-sponge reefs are delicate twisting structures of silica. Their shapes vary from maze-like branches to billowing, cauliflower-like clouds.

Until recently, nobody had been able to keep glass sponges alive long enough for meaningful study. However, Angela Stevenson, a biologist at the University of British Columbia, has pioneered research on glass sponges that flourished in her lab for a record length of time — apart from those she subjected to heat and acid to test their resilience. That impressed other researchers.

"I got an email and they were like, 'It's amazing that you've kept them two months'… I was like, 'It's actually five,'" Stevenson said. "They were like WOW!"

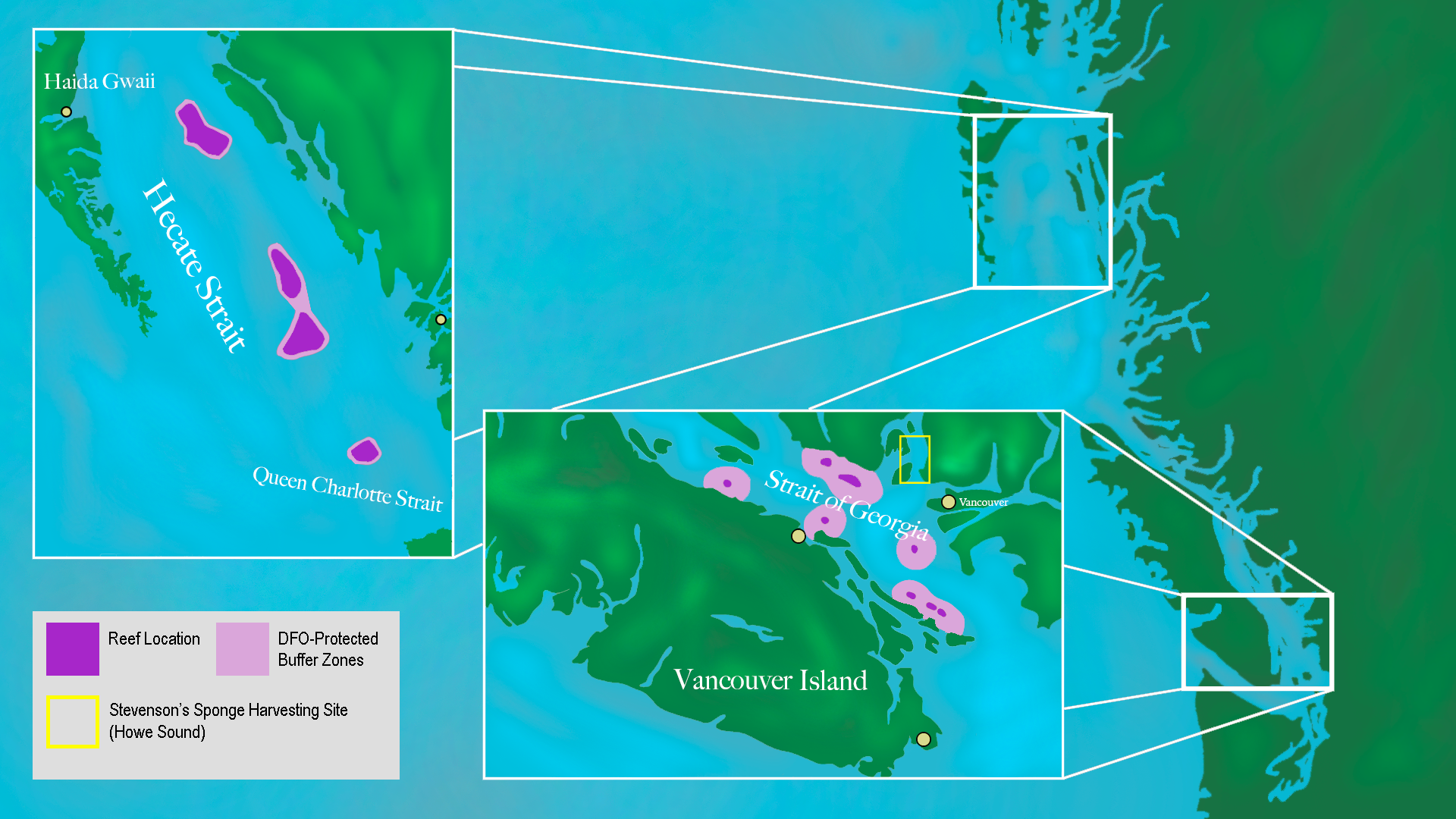

Individual sponge gardens can be found across the world, but B.C.'s expansive glass-sponge reefs are the only known ones on Earth.

Until 1986 when scientists discovered the reefs in Hecate Strait, which sits between Haida Gwaii and the northern B.C. mainland, glass-sponge reefs were thought to have disappeared 40 million years ago.

"If we re-discovered a T. Rex, people would go crazy," said Stevenson. "This is what happened with the sponge reefs."

As more glass sponge reefs continue to be discovered, scientists are becoming increasingly aware of the threat human activity poses to these living fossils. One recent reef discovery in the Broughton Archipelago was found smothered under a layer of waste from a salmon farm.

Broader concerns include warming sea temperatures and ocean acidification.

Stevenson's research raises serious questions about how climate change will affect sponges' essential role in B.C.'s marine ecosystems. Warmer ocean temperatures appear to be dramatically weakening their filter-feeding abilities, which are essential element in maintaining local food chains.

"When you change the balance, that's when you get problems," Stevenson said. "I don't know how the system will be impacted, but we are likely to see cascading effects."

Glass sponges constantly pump water through their glassy structures, taking bacteria and other small particles out of the water to use for growth.

These chimney-like tubes start by drawing in water through the pores lining their walls. Cells fixed to the inner walls then shuffle the water and food up to the top using protein whips.

Other cells grab and eat the micro-organisms floating through the water and, finally, clean water is pumped out of the top.

They're filtering the water for the entire ecosystem. Even Stevenson's little laboratory sponges are ravenous filtration machines.

"Imagine drinking 72 one-litre cartons of milk in one hour. That's one little sponge," Stevenson said.

Stevenson said this feeding process is key to B.C.'s marine environment. "They'll filter the Howe Sound in one year - the entire body of water," Stevenson said. The reefs also provide habitat for other sea life.

Based on Stevenson's lab results, all the animals in the food chain could be affected as sea temperatures and composition change.

Because of Stevenson's research, biologists now have the means and the motivation to learn more about the mysterious sponges and their importance to other species.

Stevenson spent almost three months, full-time, figuring out the best way to keep these fragile animals alive.

"I talked to a lot of people," she said. "I researched their diet and what I could feed them. I wasn't totally sold on the diets previously used."

So she decided to try feeding them a liquid diet.

Stevenson's success has not come without a tremendous amount of time and effort. She spends 12 hours a day, seven days a week in the UBC lab looking after the sponges.

"It's like having a child, but 64 children. It is! You want them to be well and happy. It's not just the science — you don't want the animals to suffer in your care," Stevenson said. "There are no holidays."

That commitment is something other researchers admire.

"No one else to my knowledge has dedicated so much time and commitment to this simple task of just trying to keep them alive," said senior research scientist Jeffrey Marliave of the Vancouver Aquarium. He's been a glass-sponge researcher and enthusiast for decades.

"We have failed so resoundingly, so repeatedly," Marliave said.

Being able to study sponges in the lab is vital if scientists are to find answers as to how they work and their role in the wider ecosystem.

The oceans make for an extremely complicated study environment because factors like temperature and acidity are always in flux. Sponges are particularly frustrating to study during research dives because they're constantly changing form.

"They're like shapeshifters," Marliave said.

Researchers have to put bar-coded stakes into the reefs, so they can tell what they're actually looking at from one season to the next. Studying animals in the lab, like Stevenson has, affords some control over the animals' environment, including in her case, temperature and water acidity.

"If we can't keep them in the lab, we can't do experiments on them," Stevenson said.

The changing seas

As climate changes increase the heat and acidity of the world's oceans, it's up to scientists to determine how the glass sponges and their ecosystems could be affected.

"I think we often think of climate change as affecting tropical reefs," said Jessica Schultz, manager of the Vancouver Aquarium's Howe Sound research and conservation team.

"But here's an example where we really want to think about what's actually happening in our own backyard and what that means for habitat we should protect."

The sponges live their lives fused to rocks or other sponges deep in the ocean where conditions are relatively stable. This means they're more sensitive to environmental shifts.

Stevenson has been testing the sponges' resilience by placing them in warmer and more acidic water.

"Will our sponge reefs be the winners or losers? We just wanted to know," Stevenson said. "Then it grew into something bigger because we focused on filtration."

Her preliminary results indicate that when water is warmer, the sponges filter water two to four times more slowly and the process is much less effective. Compounding heat with acidity makes it even worse.

"If they're stressed for too long, as it is with us, things start to break down," Stevenson said.

Stevenson's research on how climate change might affect the glass sponges is in progress, but the ramifications on the ecosystem remain to be analyzed.

"You can imagine if they're removing bacteria, viruses, protists, any small particle in the water — what if that just starts to build up?" She said changes in water composition are likely to have implications for other species on both land and sea.

"Whatever impacts the ocean, anything living in the ocean, will impact us."

This preliminary research on how B.C's glass sponges might respond to rising temperatures comes at a time when government commitments to tackling climate change are being questioned.

In February, B.C. Auditor General Carol Bellringer reported that B.C. was not on track to meet its interim targets of reducing greenhouse gases by 33 per cent below 2007 levels by 2020.

That's why climate change is a major concern for researchers like Stevenson.

"We have to speak out for those reefs," she said. "I know how much biodiversity lives on them - it's like a little treasure."

"They're not found anywhere else but here, so it's our responsibility." ![]()

Read more: Science + Tech, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: