Max Adrien stands at the corner of St. George and Sixth in Vancouver, looking down the hill towards shipping cranes that peek out of the bay. "This should be declared a Vancouver heritage site," he says.

He's standing on pavement that covers up one of Vancouver's lost creeks. It used to carry spawning salmon from False Creek up to its headwaters at present-day Robson Park. Now, those headwaters are covered over by a playground, but the park still has wet, boggy patches. The forgotten stream bubbles up from time, reminding residents of a landscape that's long since been eclipsed by urban development.

"You could argue that the creek remembers. Or, we remember," says Rita Wong, who lives by the lost creek.

You can still hear water in the storm drains, and little yellow salmon are spray-painted on the nearby curb. There's a mural near the intersection that shows the seven life stages of the salmon. Someone's written a swirling line of poetry in the sidewalk concrete: listen; the buried stream gurgles its longing to return to daylight & moonlight to nourish ducks, bracken, ferns, salmonberry & you.

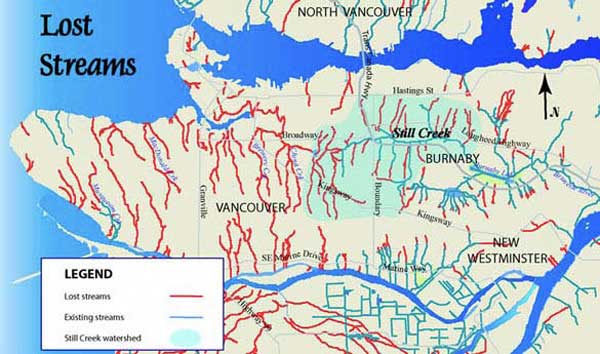

This is the St. George Rainway. Adrien and Wong are both part of a neighbourhood group that's trying to bring the old creek back to life -- or at least create a new creek on top of where it used to run. Wong helped start the project when she came across a digitized map of Vancouver's 50-odd lost salmon streams, and realized she lived right next to one.

"That map is very telling," she says. "It reminds you of what was here, and it also, I think, poses a challenge in terms of what could be here again."

Wong doesn't think she'll ever see salmon on St. George Street, since the old creek is buried under concrete. But she thinks a rainway, which would collect winter rains to create a seasonal creek, would be a good alternative.

Other once-lost streams have already seen returns. In Spanish Banks, coho and chum salmon have returned to the creek that runs along the west side of the beach and up into Pacific Spirit Regional Park. Salmon have returned, or soon will, to Still Creek, Hastings Creek and Musqueam Creek.

The city plans to one day restore Tatlow Creek along Point Grey Road. There's even long-term talk of restoring China Creek through East Vancouver all the way from Trout Lake to False Creek through a combination of closed pipes and restored streams in city parks.

One by one, the lines on the map of Vancouver's lost salmon streams are coming back to life.

Embedded with the creek restorers

On a bright Wednesday morning, I climbed down the ravine by Spanish Banks Creek in Vancouver with a group of volunteers to take part in an annual mission to reintroduce salmon to the creek, which runs through Pacific Spirit Park just west of Blanca to its mouth on Spanish Banks beach.

Clinging to a rope with one hand and holding a heavy bucket teeming with tiny silver coho fry with the other, I shakily descended into the creek's upper watershed. Before the creek was restored in 1999, a parking lot on the beach split the creek in two. It remains one of the most high-profile ecological restoration projects in the province.

The group I'm with, composed of local Spanish Banks Streamkeepers volunteers, annually releases about 2,500 new coho fry into the creek, hoping to kickstart the stream's population.

Sandie Hollick-Kenyon is the federal Department of Fisheries and Oceans community advisor for this region. Today, she's driven down from the North Shore with her truck full of fry from the Capilano hatchery.

The coho will spend about a year in the creek before going out to sea. After three or four years, they return as adults to spawn. But only about one per cent of the fish released will survive.

Nick Page developed the original restoration plan for the Spanish Banks Creek restoration, and he now works as a biodiversity consultant for the City of Vancouver. He says that no matter how small the fish population, it's still important to restore these habitats.

"These are small streams," he says. "They're not going to make or break the salmon population on the Pacific coast, but they do have a real role in increasing awareness and education."

People care about these places, and usually that's what creates the momentum to bring them back. One of the volunteers here today is Ron Gruber. He's become the public face of the creek, and its most dedicated steward.

Gruber walks the creek almost every day, checking for salmon and watching the stream grow.

"This is Ron's creek," says Hollick-Kenyon, laughing. "I'm just here to help him."

Rewilding the city

The Museum of Vancouver's "Rewilding Vancouver" exhibit imagines a future where all 50 lost salmon streams are teeming with spawning salmon. The exhibit's curator J.B. MacKinnon says that world is closer than we think.

"For the First Nations here before contact, the 'normal' state of nature in Vancouver was 120 kilometres of free-flowing streams and 100,000 spawning fish a year," says MacKinnon.

"Even in the 1980s, Vancouver still had its own salmon fishing derby. Only when we remember this history does it become possible to imagine restoring those streams and salmon."

Restoring these creeks is easier in some spots than others. At Spanish Banks, restorers still had a visible stream to work with. On St. George, where the creek is completely paved over, it's a different story.

"I would love for it to be restored, but it's technically a lot more difficult to do something in a small space that's so clenched up in terms of concrete," Wong says.

"What we can do is work with what's coming down all the time -- so that's why we've started calling it a rainway and tried to imagine making a new creek on top of what's been buried before."

She'd love to one day see a seasonal creek from winter rains, water gardens and a restored wetland.

"If you build it for it to happen, it can," she says.

Why restore streams?

When salmon first came back to Spanish Banks after the 1999 restoration, people were startled.

"It was probably the first time in the City of Vancouver in a long, long time when you could actually smell rotting salmon," says Page with a laugh. He welcomed the smell.

Salmon are a keystone species of the B.C. ecosystem. And as the salmon return to Spanish Banks, so have other animals. Hollick-Kenyon has seen mink, river otter, beavers, eagles, herons and raptors, along with new kinds of birds and colourful salamanders.

"There's an ecological argument that fish were always part of this landscape, and we have a responsibility to try to bring those things back," says Page.

For MacKinnon, it's also about starting a new age of "rewilding" urban environments.

"I love cities, but they have always felt ecologically empty to me -- I feel lonely for the company of other species," he says. "Rewilding tells us that we don't have to separate nature and culture into solitudes."

'It was amazing'

We finish our morning at Spanish Banks down by the beach, where volunteers scatter six more buckets of coho. The tide is low, and by the time the stream reaches the bay, it's just a series of trickles in the sand going out to sea.

Hollick-Kenyon thinks back to the first time she saw the salmon return. She watched about 65 chum salmon swim back up the creek, the highest number the stream has seen since it came back to life.

"When we saw them return... oh my God," she says. "To see 65 chum salmon -- these big, in-your-face fish -- come back to this little creek, you could hop over in your gum boots. It was amazing."

The fish we released that day were tiny, about the length of a single finger joint. Some of them were reluctant to leave the buckets. When tipped into the creek, they flashed in the water and then disappeared.

Many will not survive. But these restorers haven't given up hope.

"Vancouver might be the only big city on earth where another species, salmon, is so much a part of our urban identity," says MacKinnon. "We're still salmon people here, and we can use that connection to revive our lost salmon streams.

"The salmon aren't gone," he adds. "They're waiting." ![]()

Read more: Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: