"I've been in jail for so long I can't remember where anything is anymore," says Betty Krawczyk, rummaging through cupboards. She pulls out a basket and holds it up triumphantly. "So what kind of tea do you like?"

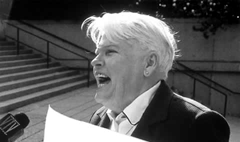

I am sitting in the modest east side apartment of Vancouver's most famous raging granny, the firebrand environmentalist who stood in front of bulldozers at Clayoquot Sound and Eagleridge Bluffs and vowed, "There will be no logging here today." I've seen her before, once standing on the steps on the law courts booming into a microphone before a throng wearing 'Free Betty' buttons and T-shirts, and in pictures of a Critical Mass rally where she was being carried around the street on a chariot like a Roman empress. So I'm a little surprised when she comes over and plops a pink napkin in my lap and asks, "Do you take honey in your tea, dear?"

Not that Krawczyk is about to go from inmate to homebody.

She is back in court this week and hopes to bring her case to the Supreme Court, where she can challenge the constitutional validity of commercially obtained injunction zones.

And she's running for mayor of Vancouver. "I got out of prison and the city's in shambles!" she shrieked to the delight of the crowd at the rally after her release. "There's garbage everywhere! Anyone can do a better job than this."

'Never felt alone'

While in jail, Betty Krawczyk read a lot in her room, took walks every day, and bonded with the other women inmates, many of whom she says were in need of a "maternal figure." She considers herself a spiritual person. At the rally at the courts the day after her release she told the crowd, "I could feel your energy. I never felt alone."

It was her eighth prison sentence, spent at the Alouette Women's Correctional Centre. Her crime was the same as before; refusing to obey a court order that instructed her to stay away from Eagleridge Bluffs, which had been turned into the site of a commercial injunction zone when construction company Kiewit & Sons gained the contract as part of the development to improve the Sea to Sky highway in preparation for the 2010 Olympics.

Krawczyk says commercial injunctions of the sort that landed her in jail "strip people of their legal rights, their rights under the charter. It's the same kind of legalities that are used to toss poor people out of substandard housing."

Krawczyk draws a connection between the endangered species being displaced at Eagleridge Bluffs, and street people in Vancouver being denied social housing in favour of new condominium construction projects. "It's like the homeless people on the downtown eastside. We're destroying their habitat. Where are they going to live? They're like the spotted owl, an endangered species. It's all the same," she says.

The only time Krawczyk shows anger is when she talks about those who "just don't care." She puts heavy intonation on the word, and screws up her mouth and nose in disdain.

I ask her why she thinks she was put in jail, and for so long. "Because I challenged a judge's order. It's about the judges -- they can do whatever they want."

The arrest of Krawczyk and others at Eagleridge Bluffs followed a pattern becoming quite familiar to protesters in B.C. The penalties for disobeying a court injunction are much heavier than for misdemeanour crimes like trespassing. Once a firm has wrangled a court injunction against direct action protest methods such as blocking a road or swarming a bulldozer, activists who disobey the injunction are seen by judges to be directly challenging the very authority of the courts.

That is why Krawczyk served more time for her protesting than do many criminals who steal or assault.

Krawczyk wants to argue in Supreme Court that use of commercial injunctions is an unconstitutional method of squelching dissent. If she wins, the decision would change the way protests are carried out, and snuffed out, in British Columbia.

Lifetime of protest

Krawczyk has a long history of activism that has spanned over decades and across borders. She is an American by birth, and first got involved with the fight to desegregate her children's school in Louisiana in the '60s, and was an outspoken agitator during the civil rights movement. She became an avid protester during the Vietnam War, and her list of complaints against her government grew even longer when she saw the Southern Wetlands become desecrated by commercial development. She was married three times, and had eight children.

After her third marriage "bit the dust," she headed north to Canada, where she purchased land near Tofino, and one of sons built her an A-frame house, where she lived happily until the logging began at Clayoquot. "You could only get there by boat," she says nostalgically. "I had always craved the wilderness, I was raised in the wilderness. I feel an affinity." She started to write a book about what she described as the "wildly beautiful," and began to meditate on all her prior activism.

"I was looking for a common denominator. I had also become a real feminist ... and I noticed the destruction by the logging." She says that seeing the destruction of the environment in her new home really brought it all together for her. "The bottom line is when the environment is getting treated in this way, so can poor people, so can poor children." She says that she drew a parallel between the environment being treated with "indifference and contempt" and the treatment of society's poor and marginalized. "The opposite of love is not hate -- it's indifference," she said. "Indifference to the land and water is indifference to life itself."

'Half-baked men fighting'

With defiance, she talks about "a lot of half-baked men fighting other men for resources," noting that women and children often get overlooked during this "male" competition for wealth and resources. She says that what links all her activism together -- desegregation, the civil rights movement, the anti-war movement, and environmentalism -- is the fight against "contempt and indifference towards life forms."

When two of her children died of cancer, Betty drew more connections between environmental pollution and her children's illnesses. She identifies as a "motherist," and a "grandmotherist," and discusses this notion in connection with her role in protecting the environment. She talks about the "grandmother theory," an anthropological query into the evolutionary aspects of menopause. "We're the only species to go through menopause ... and it's so we can help teach and feed our grandchildren," she says.

She also has a theory about "common evolution." Human evolution, she says, is meant to be in sync with animal and plant evolution. To deny common evolution is "to be drawn towards death." She means death on many levels, and sees the death of endangered species and the death of social programs that are geared towards helping the poor as symptoms of a greater cultural problem. It's all the same, as she tells it.

I ask if she would go back to prison to protect nature or the poor, and she says that she would. That would be a sacrifice, I say. She disagrees. "It's my job."

"Eagleridge Bluffs was alive," she says remorsefully, "it was teeming with life."

Related Tyee stories:

- Harriet Nahanee Did Not Die in Vain

Let's learn from Eagleridge Bluffs protest. - Showdown on the Bluffs

Protesters arrested. A public's attention captured. - Lousy Judgment

Bad politics, weird decisions: a system in need of reform.

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: